2026 Hagströmer fellowship: a residential fellowship in the history of medicine and related sciences

Dear Friends,

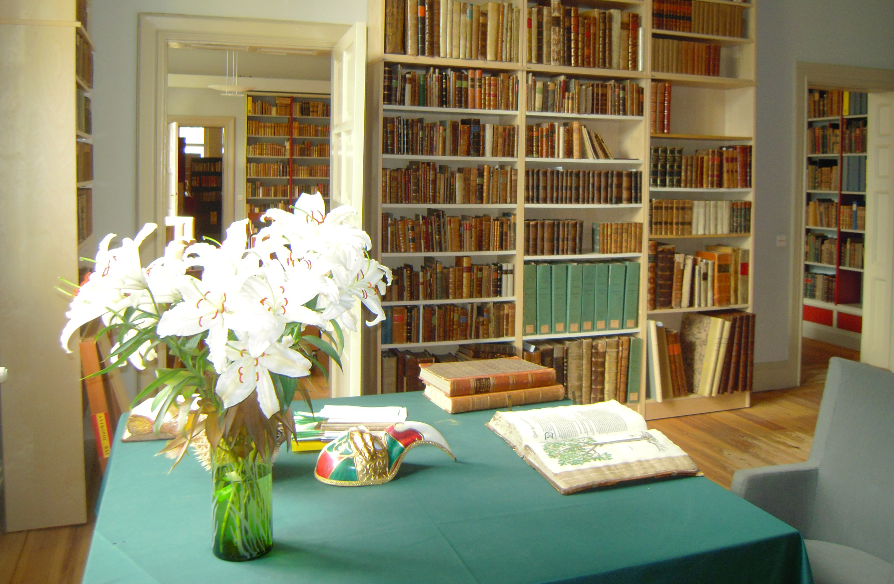

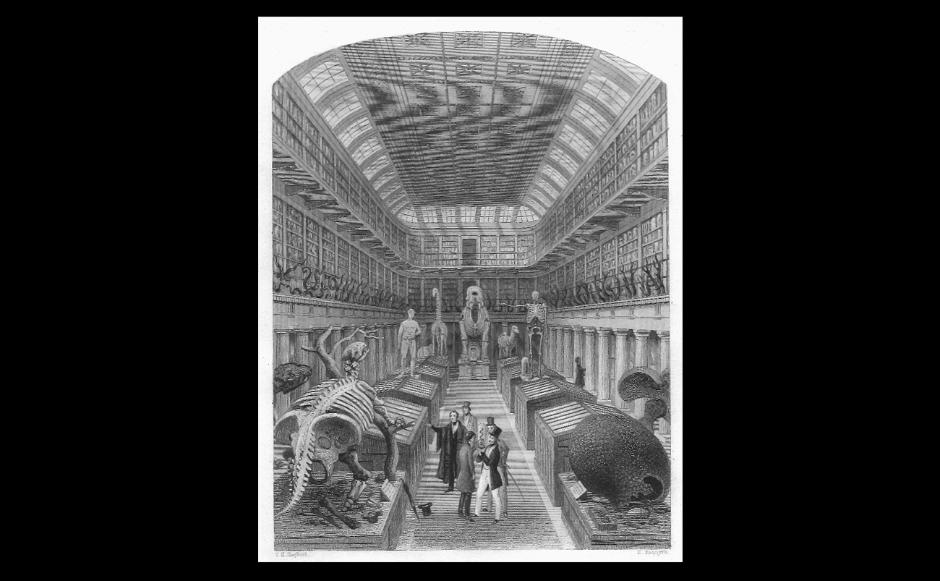

The Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library of Karolinska Institutet and the Catarina and Sven Hagströmer Foundation are now accepting applications for the 2026 Hagströmer Fellowship. The fellowship is a short to medium term research fellowship which provides a high level of integration at the Hagströmer Library in central Stockholm. We encourage applications from postdoctoral or senior researchers in the field of history of medicine and/or related sciences (early modern to twentieth-century). The Hagströmer is a part of the university library of Karolinska Institutet, and its collections contains Sweden’s largest collections in the history of medicine and related sciences, includes more than 100 000 monographs published between c. 1480 and 2000, extensive manuscript collections and c. 1300 medical and scientific journals. Detailed description The Hagströmer Fellowship is a residential fellowship (2-6 months) which supports a scholar who will travel to Stockholm to conduct research in the Hagströmer library during 2025. A sum of EUR 10 000 from The Catarina and Sven Hagströmer Foundation will be made available to cover accommodation, travel, cost of living in Stockholm, and additional insurance, if needed. Visiting scholar status at the Hagströmer library grants a workplace/ personal desk at the Hagströmer Library and access to collections (Mondays to Thursdays) for the duration of the stay. Please note, however, that the library is closed for summer between June, 21 and August 18. Affiliation status at KI grants an email address and use of library resources at Karolinska Institutet University Library (KIB) of which the Hagströmer is a part. This includes full access to scholarly databases and journals in medical sciences. The Hagströmer library expects the Fellow to spend a minimum of two months in Stockholm, to present their work at a public lecture at the library, to use the Hagströmer Library as their primary place of work, to engage with our collections and to write a short popular text about their work at the library. Application procedure The call is open until Oct. 31, 2025 and should be sent by mail to the Catarina and Sven Hagströmer Foundation cshstiftelse@hagstromer.se (please label your email ‘The Hagströmer Fellowship’). The application should be in pdf format and must include the following documents in the following order. 1. A two-page description of yourself and your research as well as a brief outline of which collections you intend to use at the Hagströmer library, and how you intend to make use of your studies of the collections in your research. Also state the duration of your visit in Stockholm and your planned date of arrival. 2. A separate page with your full name and address. This page must also include the names and contact details of two references (references will only be taken on final candidates). 3. A CV of no more than three pages outlining your major academic and other relevant accomplishments and publications. 4. A copy of your PhD-certificate/highest formal academic degree. The Fellow will receive a personal notification and the decision will be announced on the webpage of the Hagströmer Library Dec. 1, 2025; https://hagstromerlibrary.ki.se/news The Hagströmer Library is committed to fostering a diverse and inclusive research environment and encourages members of any groups that have traditionally been underrepresented in academia to apply for fellowship support. Please share this announcement with anyone who might be interested in the library’s fellowship program. All application materials are due no later than October 31, 2025. For further information about the library visit our website or e-mail hagstromerlibrary@ki.se. Thank you! Eva Åhrén and Hjalmar Fors Medical History and Heritage/Hagströmer Library, Karolinska Institutet

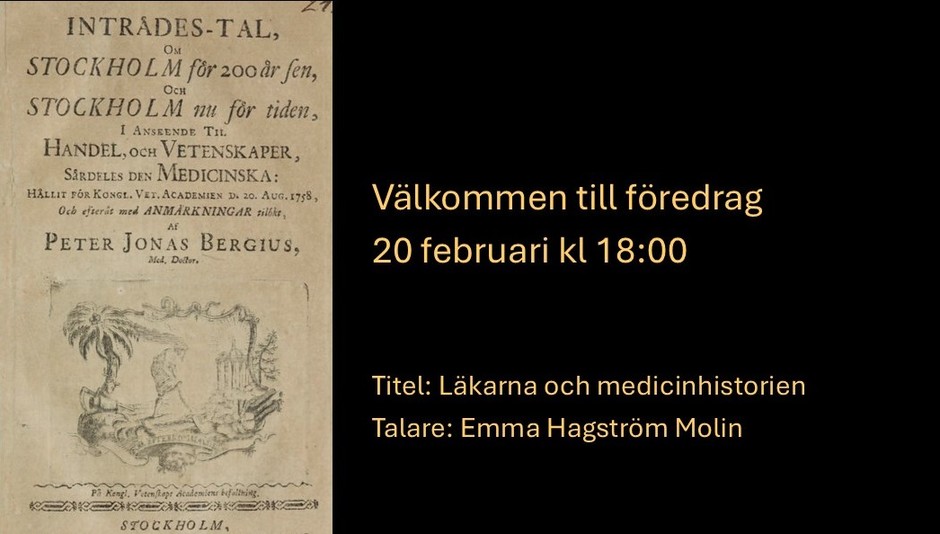

Välkommen till föredrag 20 februari - Läkarna och medicinhistorien!

VARMT VÄLKOMNA TILL VÅRENS AKTIVITETER PÅ HAGSTRÖMERBIBLIOTEKET!

FÖREDRAG:

2024 ÅRS NOBELFÖREDRAG PÅ HAGSTRÖMERBIBLIOTEKET

Tors. 30 januari, kl. 18-20, Anna Lantz

Föredrag i samarbete med Hagströmerbibliotekets Vänner. Kostnad medlem: 130kr, icke medlem: 180kr. Förfriskningar serveras.

LÄKARNA OCH MEDICINHISTORIEN

Tors. 20 februari kl. 18-20, Emma Hagström Molin, Hagströmer fellow 2024

Föredrag i samarbete med Hagströmerbibliotekets Vänner. Kostnad medlem: 130kr, icke medlem: 180kr. Förfriskningar serveras.

”SE TILL OCH GÖR EN DÅ!” OM DEN FÖRSTA INOPERERADE PACEMAKERN OCH PATIENTEN SOM FICK DEN

Tis. 1 april kl 18-20, Olle Hagman

Föredrag i samarbete med Hagströmerbibliotekets Vänner. Kostnad medlem: 130kr, icke medlem: 180kr. Förfriskningar serveras.

ICEPICKS, BRAINS AND NOBLE PRIZES: THE HISTORY OF LOBOTOMIES IN SWEDEN

Ons. 4 juni kl 18-20, Lukas Meier, Hagströmer fellow 2025

Föredrag i samarbete med Hagströmerbibliotekets Vänner. Kostnad medlem: 130kr, icke medlem: 180kr. Förfriskningar serveras.

GRATISVISNINGAR:

LIVETS SKÖRHET – KUNSKAP OM FOSTER OCH FÖRLOSSNINGAR UNDER 500 ÅR

Utställningen visas 30/10-2024 till 26/9-2025. Gratis visningar på svenska ges den 11 mars kl. 16.30, den 13 mars kl. 12.00, den 9 april kl. 12.00 och kl. 16.30, den 7 maj kl. 12.00 och kl. 16.30, den 21 maj kl. 12.00 och kl. 16.30. Visningarna ges på svenska och tar ungefär en timme. Föranmälan kan även göras i grupp men notera att antalet platser är begränsat.

Plats: Haga Tingshus, Annerovägen 12, Solna.

OBSERVERA att det finns ett begränsat antal platser både på föredrag och visningar. Obligatorisk föranmälan till hagstromerlibrary@ki.se

Vi är som vanligt även öppna för besök i forskarläsesal och bokning av guidade biblioteksvisningar. För bokning av besök, vänligen kontakta oss på mail hagstromerlibrary@ki.se.

Postadress: Hagströmerbiblioteket, Karolinska Institutet 17177 Stockholm | Besöksadress: Haga Tingshus, Annerovägen 12 Solna | Telefon: 08-52486828 | E-post: hagstromerlibrary@ki.se |

Webb: ki.se | Org. Nummer 202100 2973

Foto: Carrie Greenwood

Announcement: Lukas Meier 2025 Hagströmer Fellow

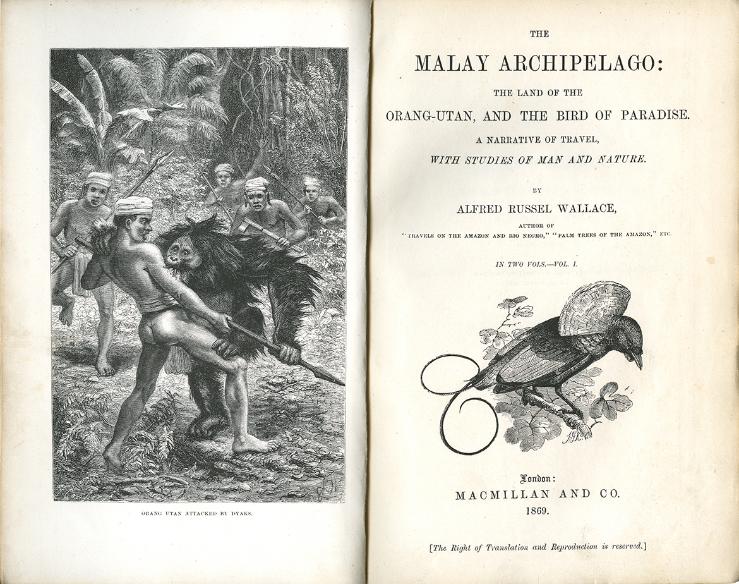

The 2025 Hagströmer Fellowship is awarded to Lukas J. Meier. Dr Meier is a fellow of the Edmond & Lily Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University, where he is conducting ethical analyses of the latest technology for stimulating the brain - so-called brain computer interfaces. Dr Meier studied philosophy at the University of Oxford and political science at the University of Göttingen and holds a PhD from the University of St Andrews. Subsequently, he was a Junior Research Fellow at the University of Cambridge. His research interests include neurophilosophy, artificial intelligence, medical ethics, philosophy of mind, and the history of these disciplines.

As our 2025 Hagströmer Fellow, Dr Meier will research the history of psychosurgery in Sweden - a project which proceeds from his investigations of brain washing during the Cold-War era and intelligence services' secret programmes in behavioural modification.

Välkommen till föredrag 14 nov. kl 18:00!

Badarna i Stockholm: Ett ämbetes uppgång och fall

Under medeltid och tidigmodern tid fanns det i Stockholm, liksom i andra svenska, finska, baltiska och nordtyska städer, publika badstugor som invånarna kunde besöka för både nöje och hälsovård. I badstugorna erbjöds besökarna bastubad – inklusive tvagning – varma karbad och kurer såsom åderlåtning och koppning. De flesta badare, och baderskor, drev sin verksamhet informellt, men under dramatiska omständigheter i samband med pestepidemin i Stockholm år 1657 fick badarämbetet i staden också skråprivilegier. I det här föredraget kommer vi få möta ett antal av de individer som drev badstugor i Stockholm från sent 1500-tal till tidigt 1800-tal. Hur förstod de sin verksamhet och dess hälsobringande effekter? Hur legitimerade badarna sin expertis i förhållande till andra hälsoprofessioner, såsom barberarna? Och vad hände egentligen inom bastuns fyra väggar? Badare utgör en ofta förbisedd grupp hälsoutövare, men när vi tittar närmare på deras roll i Stockholm under tre sekler framträder en ny bild av föränderliga ideal och praktiker kring hälsa. Charlotta Forss är biträdande lektor i historia vid Södertörns högskola. Hon har för närvarande ett forskningsprojekt som handlar om väder och identitet i Östersjöområdet under tidigmodern tid. Hon har tidigare forskat om hälsa och moral i den tidigmoderna bastun och hennes senaste publikationer inkluderar antologin Health in Early Modern Sweden utgiven av Amsterdam University Press (2024). TORSDAG 14 NOV KL. 18.00 Hagströmerbiblioteket Haga Tingshus Buss 515 (Odenplan) Hållplats Haga Södra Anmälan emotses före tisdag 12 november Email: info@hagstromerbiblioteketsvanner.se Telefon: 070 555 27 36 Förfriskningar serveras, Medlemmar inträde 130 kr Icke medlemmar 180 kr

2025 Hagströmer fellowship: a residential fellowship in the history of

medicine and related sciences

Dear Friends,

The Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library of Karolinska Institutet and the Catarina and Sven Hagströmer Foundation are now accepting applications for the 2025 Hagströmer Fellowship. The fellowship is a short to medium term research fellowship which provides a high level of integration at the Hagströmer Library in central Stockholm. We encourage applications from postdoctoral or senior researchers in the field of history of medicine and/or related sciences (early modern to twentieth-century). The library is a part of the medical university Karolinska Institutet, and its collections contains Sweden’s largest collections in the history of medicine and related sciences, includes more than 100 000 monographs published between c. 1480 and 2000, extensive manuscript collections and c. 1300 medical and scientific journals.Detailed description

The Hagströmer Fellowship is a residential fellowship (2-6 months) which supports a scholar who will travel to Stockholm to conduct research in the Hagströmer library during 2025. A sum of EUR 10 000 from The Catarina and Sven Hagströmer Foundation will be made available to cover accommodation, travel, cost of living in Stockholm, and additional insurance, if needed. Visiting scholar status at the Hagströmer library grants a workplace/ personal desk at the Hagströmer Library and access to collections (Mondays to Thursdays) for the duration of the stay. Please note, however, that the library is closed for summer between June, 21 and August 18. Affiliation status at KI grants an email address and use of library resources at Karolinska Institutet Library (KIB), including full access to scholarly databases and journals in medical sciences. The Hagströmer library expects the Fellow to spend a minimum of two months in Stockholm, to present their work at a public lecture at the library, to use the Hagströmer Library as their primary place of work, to engage with our collections and to write a short popular text about their work at the library. Application procedure The call is open between Oct. 1 and Nov 10, 2024 and should be sent by mail to the Catarina and Sven Hagströmer Foundation cshstiftelse@hagstromer.se (please label your email ‘The Hagströmer Fellowship’). The application should be in pdf format and must include the following documents in the following order. 1. A two-page description of yourself and your research as well as a brief outline of which collections you intend to use at the Hagströmer library, and how you intend to make use of your studies of the collections in your research. Also state the duration of your visit in Stockholm and your planned date of arrival. 2. A separate page with your full name and address. This page must also include the names and contact details of two references (references will only be taken on final candidates). 3. A CV of no more than three pages outlining your major academic and other relevant accomplishments and publications. 4. A copy of your PhD-certificate/highest formal academic degree. The Fellow will receive a personal notification and the decision will be announced on the webpage of the Hagströmer Library Dec. 16, 2024;https://hagstromerlibrary.ki.se/news

The Hagströmer Library is committed to fostering a diverse and inclusive

research environment and encourages members of any groups that have

traditionally been underrepresented in academia to apply for fellowship

support.

Please share this announcement with anyone who might be interested in

the library’s fellowship program. All application materials are due no later

than November

10, 2024. For further information about the library visit our

website or e-mail hagstromerlibrary@ki.se.

Thank you!

Eva Åhrén and Hjalmar Fors

Medical History and Heritage/Hagströmer

Library, Karolinska InstitutetFoto: Greger Hatt

GLAD SOMMAR FRÅN OSS PÅ HAGSTRÖMERBIBLIOTEKET

Vi har haft en intensiv vår med många fina evenemang och aktiviteter. Särskilt vill jag nämna den alldeles fantastiska konstutställningen Toxic Transits i Tingssalen. Den utforskade samspelet mellan mänskliga kroppar, metaller och mineraler, och miljö. Verken som visades inkluderade till exempel tårar som kristalliserats till juveler, och mässingsplåtar som avbildar traditionella kongolesiska ärrtatueringar. Utställningen går fortfarande att ta del av. Tyvärr inte längre på Hagströmerbiblioteket, men dock genom en bok av kuratorerna Beatrice Brovia och Nicolas Cheng. Boken heter också Toxic Transits och går att köpa genom oss. Den är dessutom nummer 28 i Hagströmerbibliotekets skriftserie. Även nummer 27 i serien släpps inom kort. Den är skriven av Olle Hagman och heter ’Se till och gör en då!’: Om den första inopererade pacemakern och om patienten som fick den. Den är ett slags fördjupad patientberättelse med dubbla perspektiv, dels författarens, dels Arne Larssons. Larsson var alltså den första patient som fick en inopererad pacemaker. Det uppstår ett väldigt fint samspel mellan dessa två berättelser. Ja, där var några små inblickar i vår verksamhet, samt kanske även lästips för hängmattan? Många sköna bad önskar vi på Hagströmerbiblioteket!

Hjalmar Fors

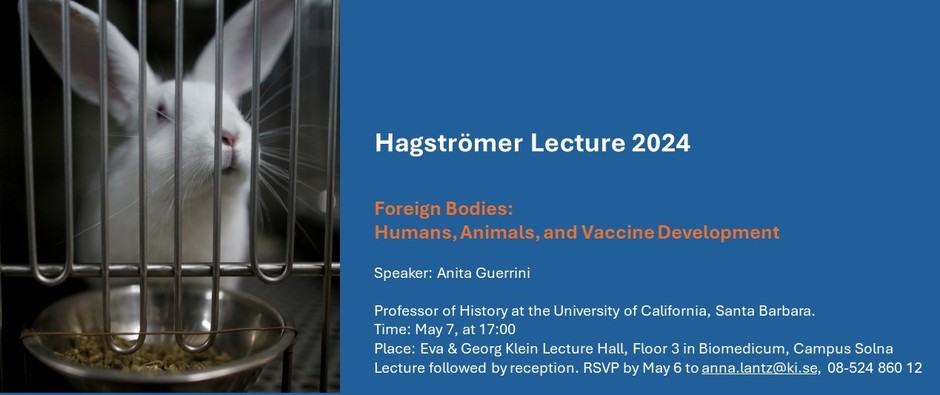

Now on Youtube: Hagströmer Lecture 2024

Inauguration speech for the exhibitionClarity and Truth, the Life of Jacob Berzelius in Biomedicum, Karolinska Institutet, 18 December, 2023

We have worked in this beautiful

building five years now. It’s full of life, full of science, full of productive

chance encounters.

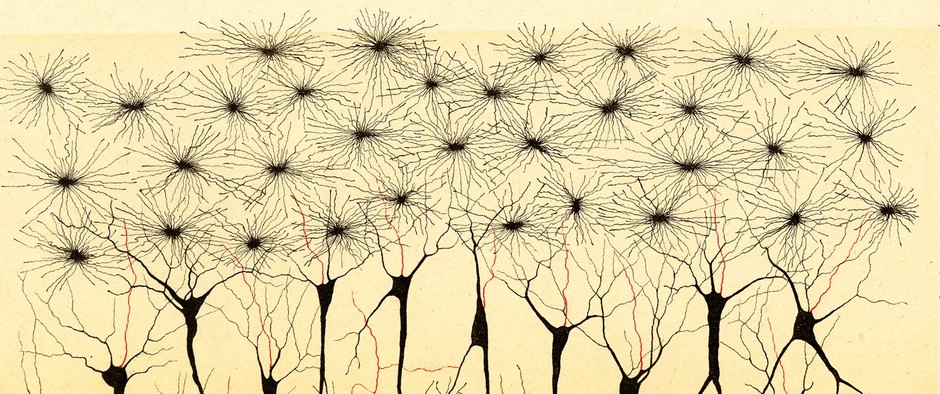

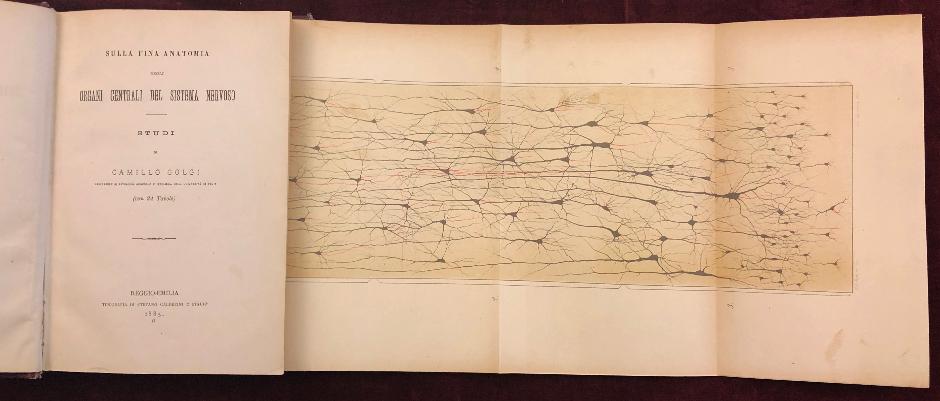

Image: Camillo Golgi,Sulla fina anatomia degli organi centrali del sistema nervoso.

Reggio-Emilia, Stefano Calderini e figlio, 1882, 1883, 1885.

[1] Funes, the memorious, 1944. “Two or three times he had reconstructed an entire day; he had never once erred or faltered, but each reconstruction had itself taken an entire day.”

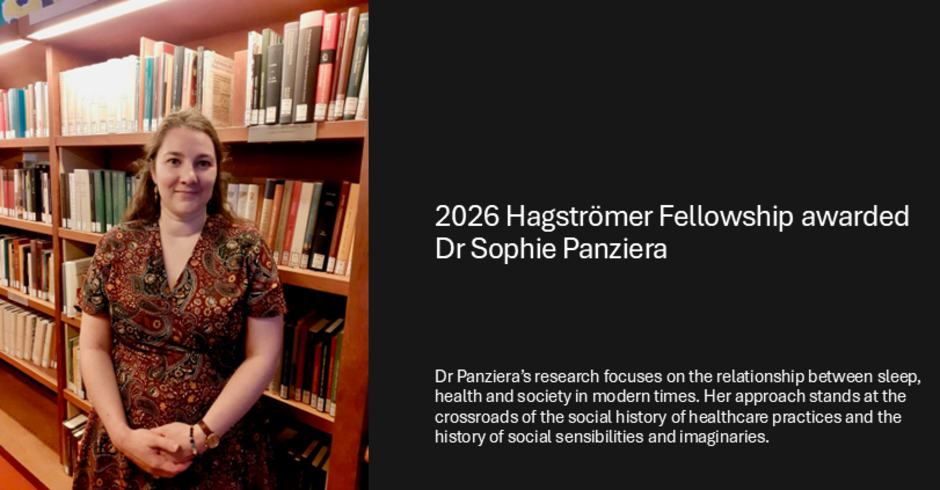

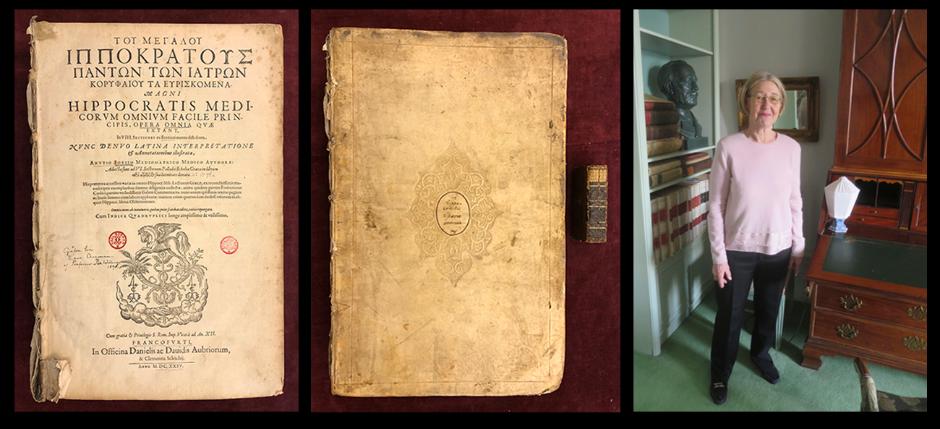

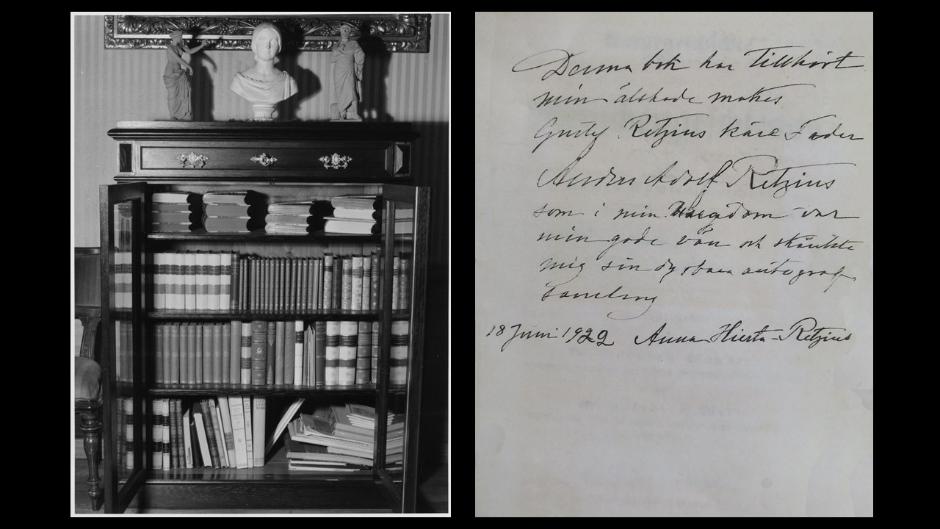

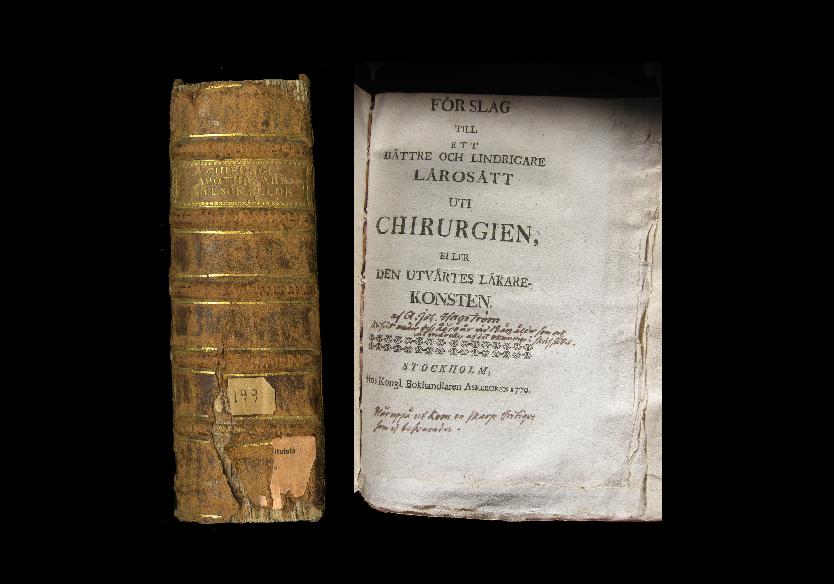

Announcement: Emma Hagström Molin the 2024 Hagströmer Fellow

The 2024

Hagströmer Fellowship is awarded to Emma Hagström Molin. During her time as

Fellow, Hagström Molin will study the ‘Swedish History of Medicine and Science

Told Through its Archives and Libraries’. She will investigate how medical

doctors and librarians began to historicize and nationalize medicine and

medical knowledge towards the end of the eighteenth century. The aim of the

study is to uncover how libraries and archives were created, and conceived, as

repositories bearing witness to a national history of medicine.

2024 Hagströmer fellowship: a residential fellowship in the history of medicine and related sciences

Dear Friends,

The Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library of Karolinska Institutet and the Catarina and Sven Hagströmer Foundation are now accepting applications for the 2024 Hagströmer Fellowship. The fellowship provides a postdoctoral or senior researcher in the field of history of medicine and/or related sciences (early modern to twentieth-century) with financial support to explore the collections of the Hagströmer Library. The Hagströmer library contains Sweden’s largest collections in the history of medicine and related sciences, including more than 100 000 monographs published between c. 1480 and 2000, extensive manuscript collections and c. 1300 medical and scientific journals. In addition, the 2024 fellowship provide opportunity to work in the archives of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, kept at its Center for History of Science. We encourage applications which make use of both collections.Application procedure The call is open between Nov. 1 and Nov. 30, 2023 and should be sent by mail to the Catarina and Sven Hagströmer Foundation cshstiftelse@hagstromer.se (please label your email ‘The Hagströmer Fellowship’). The application should be in pdf format and must include the following documents in the following order. 1. A two-page description of yourself and your research as well as a brief outline of which collections you intend to use at the Hagströmer library, and how you intend to make use of your studies of the collections in your research. Also state the duration of your visit in Stockholm and your planned date of arrival. 2. A separate page with your full name and address. This page must also include the names and contact details of two references (references will only be taken on final candidates). 3. A CV of no more than three pages outlining your major academic and other relevant accomplishments and publications. 4. A copy of your PhD-certificate/highest formal academic degree. The Fellow will receive a personal notification and the decision will be announced on the webpage of the Hagströmer Library Dec. 15, 2023; hagstromerlibrary.ki.se The Hagströmer Library is committed to fostering a diverse and inclusive research environment and encourages members of any groups that have traditionally been underrepresented in academia to apply for fellowship support. Please share this announcement with anyone who might be interested in the library’s fellowship program. All application materials are due no later than November 30, 2023. For further information about the library visit our website or e-mail hagstromerlibrary@ki.se. Thank you! Eva Åhrén and Hjalmar Fors Medical History and Heritage/Hagströmer Library, Karolinska Institutet Karl Grandin Center for History of Science, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Välkommen till ett nytt läsår med Hagströmerbiblioteket!

Höstterminen har rivstartat med många bokade visningar och forskarbesök! Snart drar vi iäven gång våra populära föredragskvällar i HBV:s regi. Först ut är Johan Wennerberg som håller sitt föredrag "Kampen mot tuberkulos" torsdag den 21 september kl 18.

Håll ögonen öppna och följ oss här på hemsidan eller i sociala media, för vi har en spännande höst framför oss här på biblioteket!

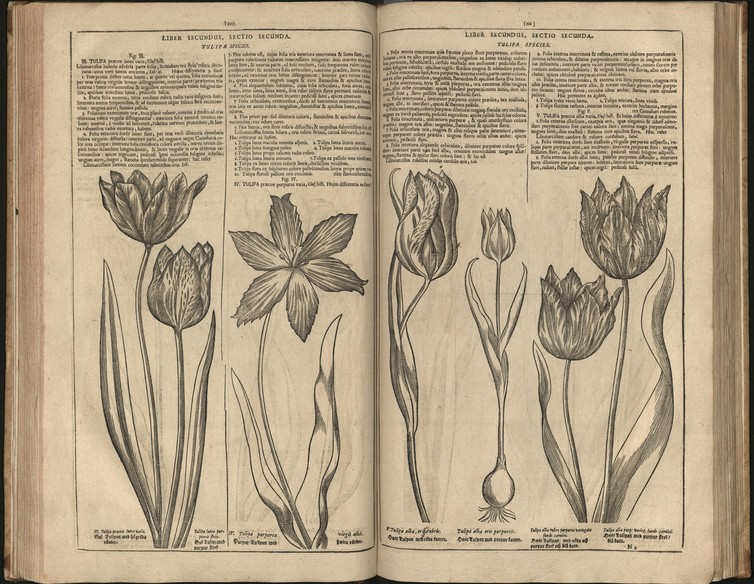

Campi Elysii Liber Secundus. . . Olof Rudbäck d.ä. Uppsala (1696) - 1701.

God Jul och Gott Nytt År!

Season´s Greetings and Best Wishes for the New Year from the Hagströmer Library!

Photo: Greger Hatt

Announcing the 2023 Hagströmer Fellow!

Vincent

Roy-Di Piazza is a historian of science, religion

and the global Northern World. He is also a specialist of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772)

and his posterity. Vincent recently obtained his DPhil in history of science,

medicine, economic and social history from the University of Oxford in 2022. An

Associate Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a postdoctoral associate

at Oxford, he has been a Fellow of the Fondazione Cini in Venice, Italy, the

Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and a visiting researcher at the

department of history of science and ideas at the University of Uppsala.

As

a Hagströmer Fellow, Vincent will conduct new research on Swedenborg’s famous treatise

on copper (De Cupro, 1734) based on a rare first edition and related literature

preserved in the Hagströmer collections. You can follow him on social media via

Twitter: @RoyDiPiazza and on his personal website: roydipiazza.com.

Welcome to the Hagströmer Lecture 2022!

The pandemic of Covid-19 has seen a renewed interest in medical history and the sort of expertise only professional historians can offer. But how can historical perspectives inform scientific responses to emerging infectious diseases and could an appreciation of the deep history of pandemics have contributed to better responses to Covid-19? Drawing on their extensive research on the history of epidemics and pandemics, the two distinguished speakers will put recent experiences into historical perspective, while posing questions for the future.

Speakers:

David Morens, M.D., National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease

Emerging epidemics: 5,000 years of existential threats

David M. Morens is Senior Advisor to the Director, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Institutes of Health, which he joined in 1998. He is trained in pediatrics, preventive medicine, infectious diseases, and virology. Dr. Morens has served as a Public Health Service officer in various capacities at the Center for Disease Control. He was also Professor of Tropical Medicine; Microbiology; Epidemiology, and Public Health at the University of Hawai‘i School of Medicine. Dr. Morens has authored hundreds of scientific articles in major biomedical journals. His career interest for over 45 years has been the study of emerging infectious diseases. He speaks and writes frequently on numerous aspects of emerging diseases, on viral disease pathogenesis, and on the history of medicine and public health.

Mark Honigsbaum, PhD, University of London

Remembering Pandemics, Imagining Covid-19

Dr Mark Honigsbaum is a medical historian, journalist and academic with wide-ranging interests encompassing health, technology, science and contemporary culture. A regular contributor to The Lancet and The Observer, he is the author of five books including Living With Enza: The Forgotten Story of Britain and the Great Flu Pandemic of 1918 (2009) and The Pandemic Century: One Hundred Years of Panic, Hysteria and Hubris (2019) which was named a “health book of the year” by the Financial Times and “science book of the year” in The Times. A former Wellcome Research Fellow, Mark is currently a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Journalism at City, University of London, where he teaches an MA specialism in health and science reporting and is researching the relationship between pandemics and cultural memory.

Moderator:

Jessica Norrbom, PhD, Karolinska Institutet

Jessica Norrbom is a researcher and lecturer at KI:s Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, specialized in molecular exercise physiology. She also has a large interest in popular science communication and was awarded “Enlightener of the year 2021” for her work with debunking health myths through books and podcastsPandemic Futures, Pandemic Pasts

TIME: NOVEMBER 16, AT 17:00 PLACE: EVA & GEORG KLEIN, FLOOR 3 IN BIOMEDICUM Lecture followed by reception. RSVP by November 9 to anna.lantz@ki.se 08-524 86012

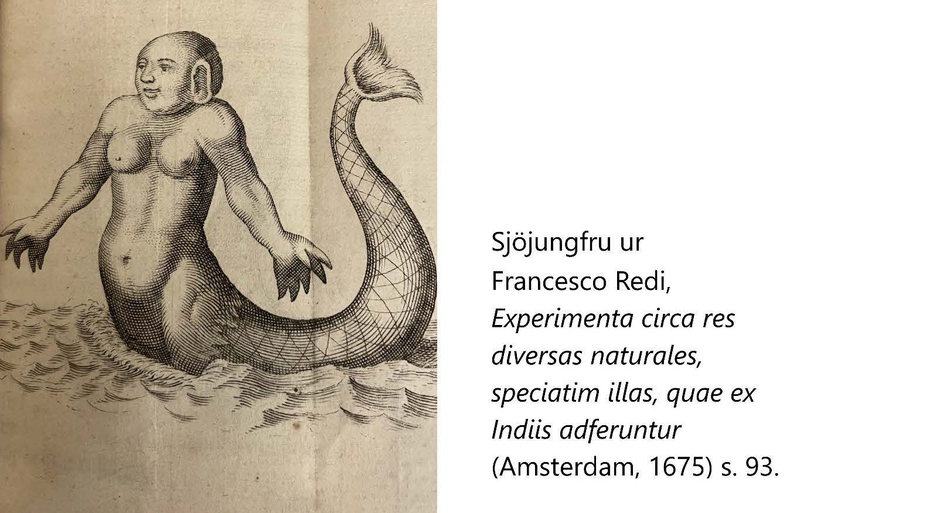

Verket Nya Liv i byggnaden Life City av David Molander

Nya Liv – är ett 35 meter långt konstverk i 13 delar som sträcker sig genom byggnaden Life City i Hagastan Stockholm. Konstverket bygger på begreppet Life Science / Livsvetenskap och bildmaterialet kommer främst från Hagströmmerbibliotekets samlingar, men även flera andra källor som Subic lab, Human Protein Atlas, och google earth. Konstnären David Molander jobbar ofta just med collage där han ombearbetar materialet till helt nya bilder. Bland detaljerna kan man se avbildningar av livets uppkomst på jorden, hjärnröntgen, mikroskopiska illustrationer av celler, vulkanska system, riktiga och påhittade djur, numeriska ekvationer, den så kallade ödlekvinnan. I en av delarna har konstnären använt utraderade porträtt av kända botaniker som ersatts av speglar så att betraktaren själv tar deras plats i skapelsens krona. Du är välkommen att gå in och titta på verket i byggnaden på Solnavägen 3 som är öppet under kontorstid.

En film som visar verkets tillblivelse kan ses här.Zoombar bild av verket kan ses här.

Text och bild: David Molander

Hagströmer fellowship in the history of medicine and/or related sciences

Välkommen till ett nytt läsår med Hagströmerbiblioteket!

Höstterminen har rivstartat med många bokade visningar och forskarbesök.

Nu drar vi också igång våra populära föredragskvällar i HBV:s regi. Först ut

blir årets Hagströmer Fellow, fil. dr. Raissa Bombini, som redan den 24:e

augusti kommer att hålla föredraget Precious stones in late medieval and early modern plague medicine.

Photo: Greger Hatt

Glad midsommar!

Tack alla vänner och besökare för ett fint år!

Bibliotekets läsesal är stängd från 27 juni - 16 augusti.

Väl mött till hösten!

New date for "Precious stones in late medieval and early modern plague medicine"

Raissa Bombini´s lecture scheduled for 1 June has been re-scheduled for 24 August instead because of traffic problems in Stockholm city.

If you have any questions please contact:

Anna Lantz 070-712 95 75 anna.lantz@ki.se

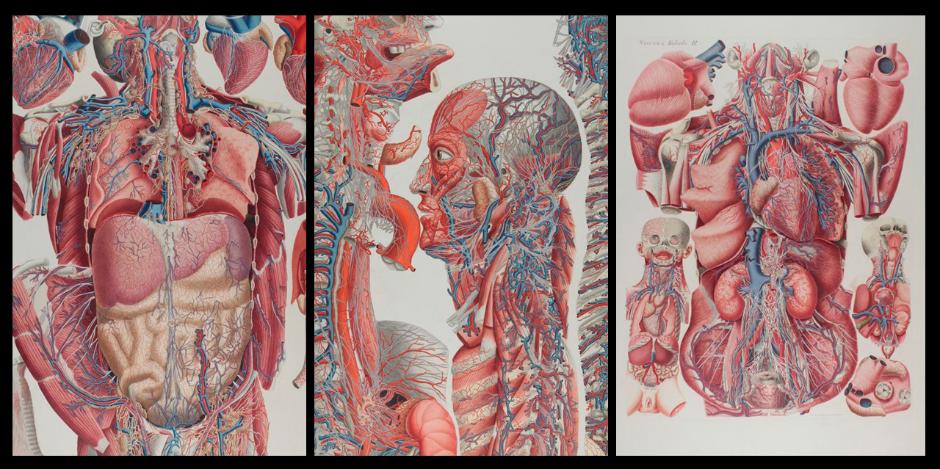

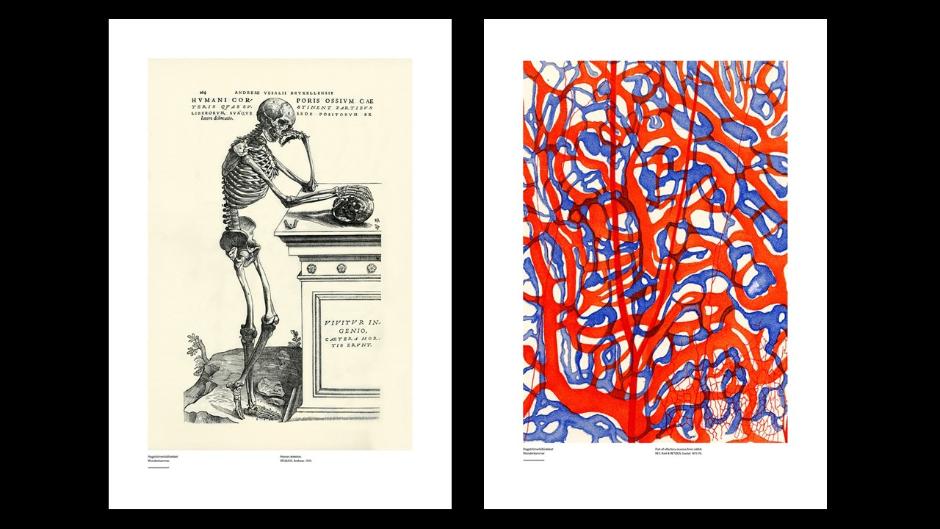

Anatomical images become art in the Berzelius Laboratory - Anatomiska bilder blir till konst i Berzeliuslaboratoriet

The Hagströmer Library provides the art on display in the Department of Neuroscience's newly renovated premises on the 6th floor of the Berzelius Laboratory. The theme is classical anatomy and early microanatomy (histology). Beautiful and striking images from works by Andreas Vesalius, Camillo Golgi, Ramon y Cajal, Paolo Mascagni and other historical researchers are what meet visitors and students. The selection was made by Professor Björn Meister in collaboration with the Hagströmer Library, which was also responsible for reproduction and framing.

The Department of Neuroscience is responsible for teaching anatomy, histology and neuroscience in several educational programs at Karolinska Institutet. Every year, more than 2,000 students pass through the department, and many others use or pass through the premises. We have received a very positive response from staff, visitors, and students, says Björn. You can often see people stopping in the corridor to look at different images. All images are illustrations from scientific books, and they are not only in the corridor but also in the teaching rooms and in the room for tutors, ie. students who have completed the course in anatomy with good results and who work as teachers in anatomy. Each semester, 40 students are offered to become tutors in anatomy. It is very popular among students to work as teachers in order to deepen their knowledge of anatomy. We often get double the number of applicants, says Björn.

Hagströmerbiblioteket står för konsten vid undervisningsavdelningen i institutionen för neurovetenskaps nyrenoverade lokaler på plan 6 i Berzeliuslaboratoriet. Temat är klassisk anatomi och tidig mikroanatomi (histologi). Vackra och slående bilder ur verk av Andreas Vesalius, Camillo Golgi, Ramon y Cajal, Paolo Mascagni och andra historiska forskare är det som möter besökare och studenter. Urvalet har gjorts av professor Björn Meister i samarbete med Hagströmerbiblioteket, som också stått för reproduktion och inramning.

Institutionen för neurovetenskap är ansvarig för undervisning i anatomi, histologi och neurovetenskap inom flera utbildningsprogram vid Karolinska Institutet där studenter från läkarprogrammet och ämnet anatomi dominerar. Fler än 2.000 studenter passerar varje år institutionens undervisningsorganisation och det är stundtals mycket folk som rör sig i lokalerna. Vi har fått väldigt positiv respons från personal, besökare och studenter, berättar Björn. Man kan ofta se personer stanna upp i korridoren för att betrakta olika bilder. Samtliga bilder är illustrationer ur vetenskapliga böcker och de finns förutom i korridoren även i kursexpeditionen och i rummet för tutorer, dvs. studenter som genomgått kursen i anatomi med bra resultat och som verkar som lärare i anatomi. Varje termin erbjuds 40 studenter att bli tutor i anatomi. Det är mycket populärt bland studenter att verka som lärare och fördjupa sina kunskaper i anatomi. Vi får ofta det dubbla antalet sökande, säger Björn.

Text: Hjalmar Fors, 28 January 2022

Season´s Greetings and Best Wishes for the New Year from the Hagströmer Library!

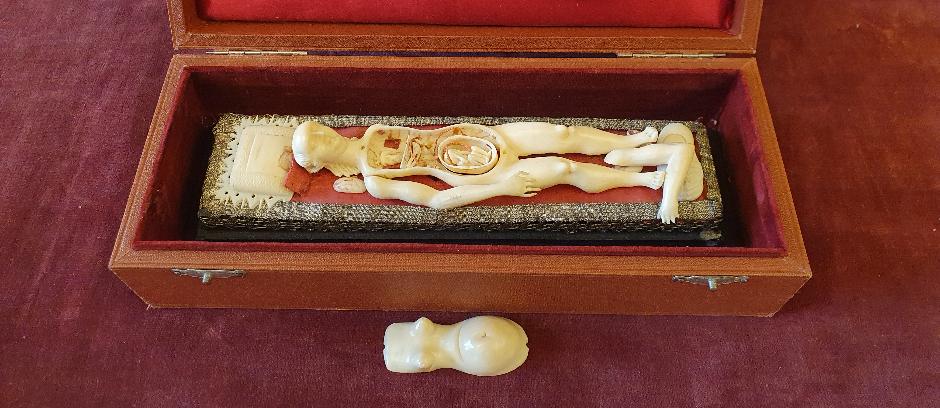

This lady is an anatomical manikin made from ivory, and she is pregnant. Made in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there exists about 180 of these manikins in museums, libraries, and private collections. Their exact function is unknown, but they clearly provided anatomical instruction. They often came in pairs, one female and one male, and it is quite likely that they were used to give instructions to newlyweds of the upper echelons of society. Ours was probably made by the Nuremberg ivory turner Stephan Zick (1639-1715). Perhaps she was made to be a wedding gift, or to be used by midwives to teach women about their bodies? She was handed over to us for safekeeping by the Department of Women’s and Children’s Health at Karolinska Institutet earlier this December. We do not know when she arrived at KI but judging from the age of the repurposed instrument box in which she came, she may have been with us a hundred years or so.

Do not forget to keep an eye out for events and exhibitions in Haga Tingshus and online during 2022! And if you have not already: please visit our temporary exhibit Dürer to Daumier: Artists of science in the collections of the Hagströmer Library. Welcome back in 2022!

GLAD SOMMAR FRÅN HAGSTRÖMERBIBLIOTEKET!

Ett år har gått sedan det sist var sommar, och vi har

verkligen saknat vår viktigaste resurs: våra besökare och vänner! Men till

hösten hoppas vi kunna öppna för visningar igen. Den 25/8 öppnar läsesalen, och

vi kommer även att fortsätta erbjuda digitala visningar och hybridvisningar

(alltså när en del av besökarna är på plats, och en del finns med på

videolänk). Fler filmer för KI:s youtubekanal är också på gång, liksom

webbutställningar. Vi hoppas också kunna återuppta våra populära föreläsningar

i Hagströmerbibliotekets Vänners regi.

Ser man tillbaka på läsåret 2020/21 har fokus varit på

katalogisering, digitalisering, städning och gallring. I den nationella

databasen Libris hade vi förut cirka 500 poster, men har nu 6299. Där finns nu

all referenslitteratur från de senaste 30 åren, viktiga delsamlingar (Linné,

Scheele, Berzelius mm) och många sällsynta böcker som inte finns på andra

svenska bibliotek. Under året har vi också kommit igång med att publicera

material i Alvin, en plattform för digitala samlingar och digitaliserat

kulturarv. Ett särskilt fokus har varit texter av och kring Carl von Linné. I

samband med inventering av materialet har vi med viss förvåning kunnat

konstatera att HB har en av världens största samlingar med manuskript kopplade

till Linné och Linneanerna. Endast, Uppsala Universitet, Linnaean Society i

London och möjligen även K. Svenska Vetenskapsakademien har större samlingar.

Vilka samlingar som är mest intressanta är något vi får tvista om. I Alvin har

vi även publicerat medicinhistoriska museet Eugenias bildsamling av svenska

sjukhus och mer är på gång, bland annat KI:s porträttsamling.

Läsåret 2021/22 blir konstens år på Hagströmerbiblioteket.

1/9 har vi vernissage för en ny utställning med arbetsnamnet Dürer till

Daumier: Vetenskapens konstnärer i Hagströmerbibliotekets samlingar Den är skapad av vår kurator Anna Lantz och visar

illustrationer i böcker och grafiska blad ur bibliotekets egna samlingar.

Senare under vintern presenterar vi två utställningar i samarbete med konstnärerna

Jenny Åkerlund och Ida Rödén. Åkerlunds verk av glas och papper baseras på

teman som optik och oftalmologi. Rödéns arbeten kretsar kring den fiktive

Linnélärjungen Jonas Falck.

Ha en riktigt skön sommar, och väl mött på

Hagströmerbiblioteket i höst!

Hjalmar Fors

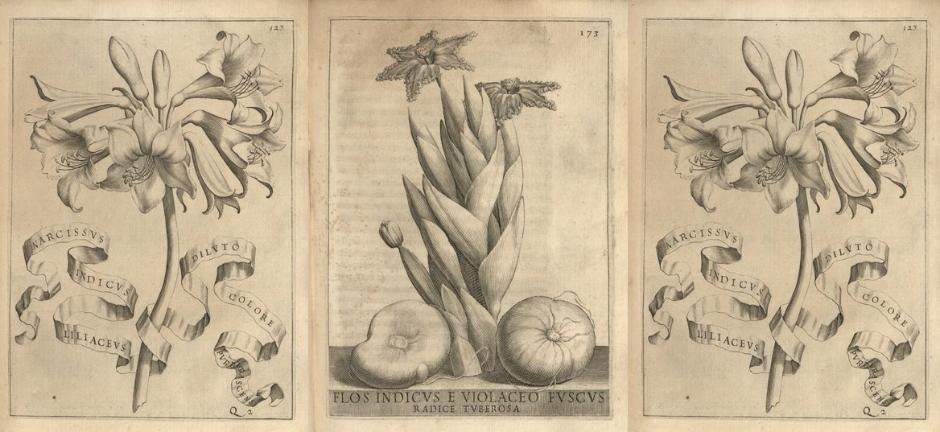

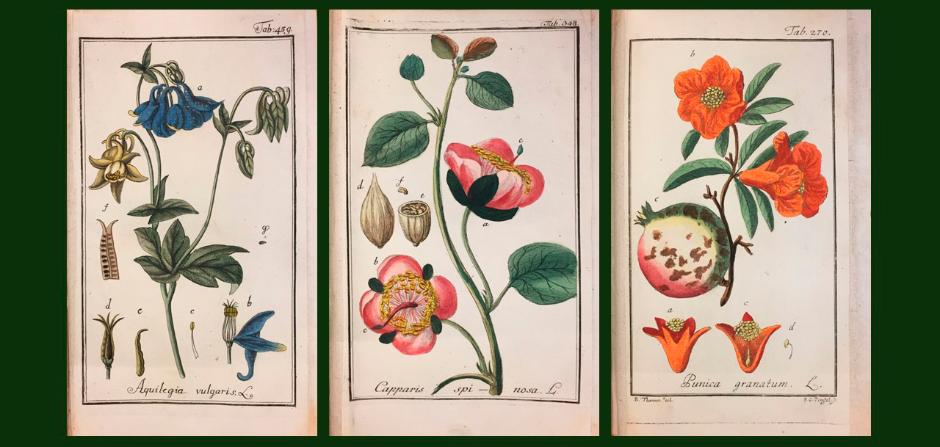

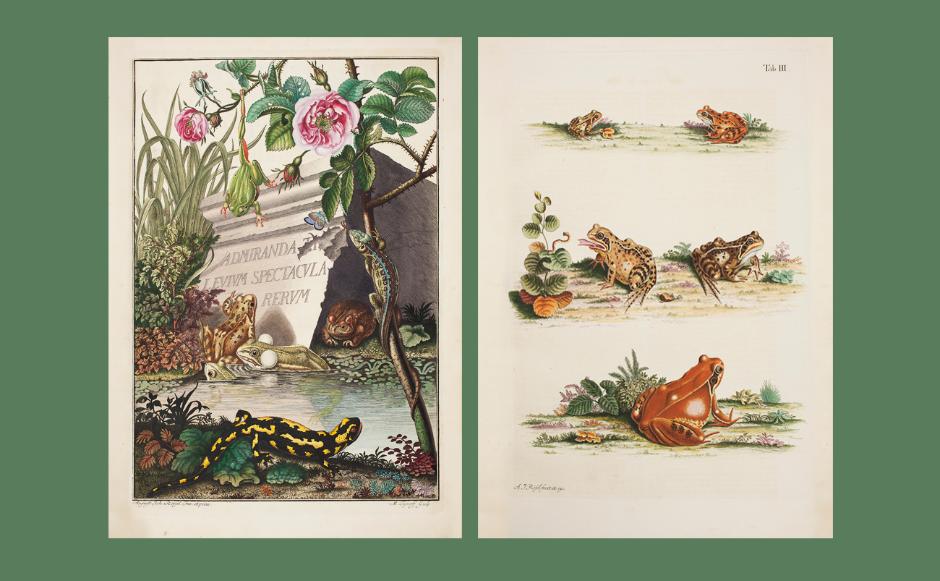

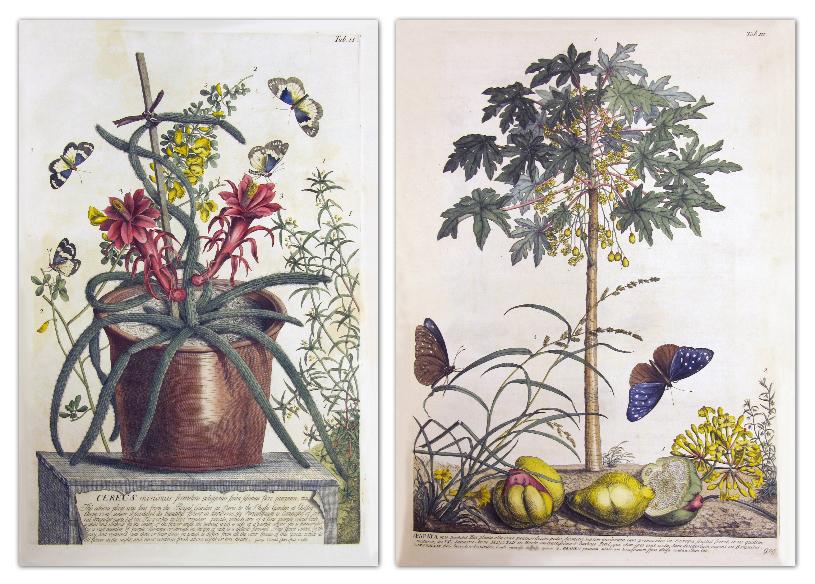

Anna Maria Vaiani

These beautiful engravings

were done by Anna Maria Vaiani (ca 1604-1655), one of only a few known women

artists represented in the Hagströmer Library collections. She was an Italian

printmaker, flower painter, and miniaturist from Florence. The images are from

the first printed treatise on floriculture, Flora overo cultura di fiori

written by Giovanni Battista Ferrari (1584–1655) and printed in Rome 1638. It

is a rare and interesting book, with illustrations depicting some of the rare

and exotic flowers in the luxurious Barberini gardens on the Quirinale in Rome.

Text and photo: Anna Lantz

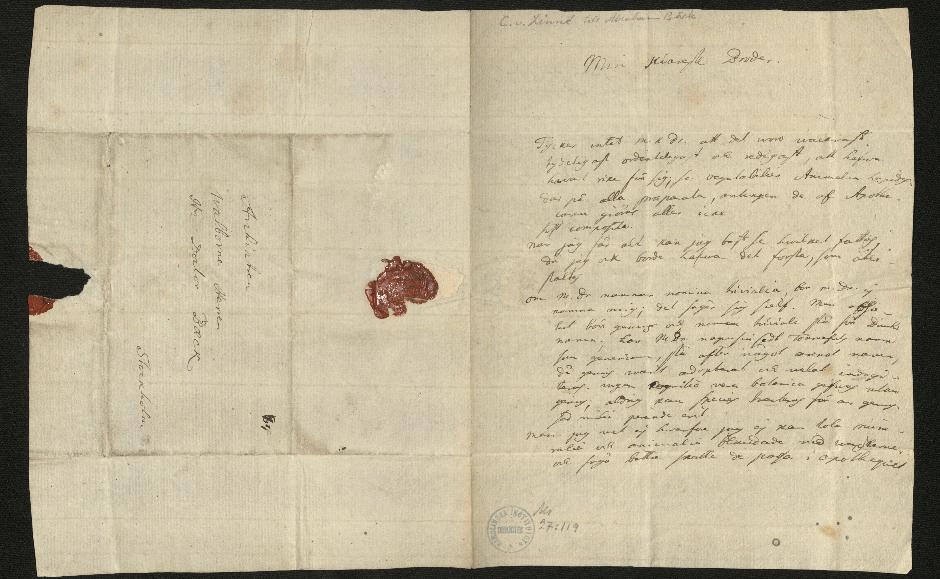

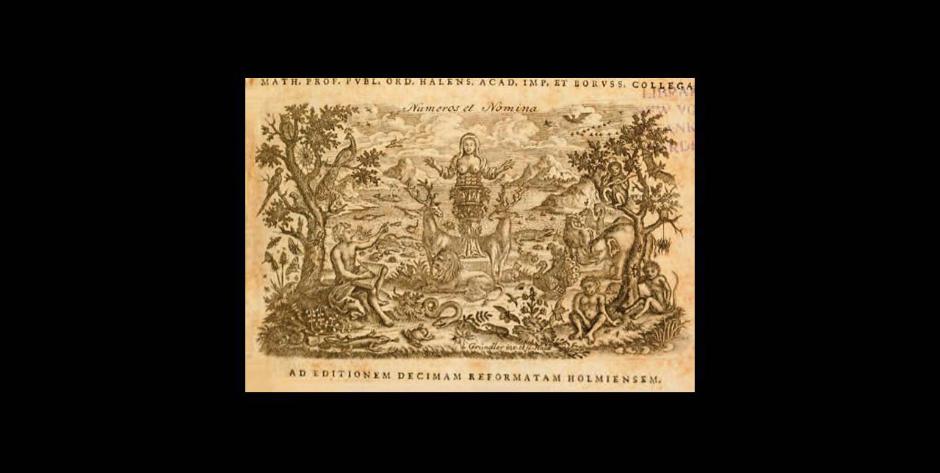

Papers holding the world together - A conference on the written heritage of Carl Linnaeus and the Linneans, May 11, 2021

Works

by, and about Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) and the Linneans form an important

subset of the Hagströmer library collections. Linnaeus was by profession a

medical doctor and this was also true for many of his close friends,

collaborators, and students. As time passed a great number of documents and

books with Linnean provenance ended up in the two major medical libraries of

Stockholm, the library of Karolinska Institutet, and the library of the Swedish

Society of Medicine. It is these two libraries that form the core of the

Hagströmer. Despite of their importance, these collections are largely unknown

to most historians of natural history and medicine. They are, indeed, even

rarely accessed by scholars of Linnaeus.

On May 11, 2021 a zoom

conference was hosted by the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library of Karolinska

Institutet,. Organized by Hjalmar Fors and Eva B. Nyström, the conference

invited a group of prominent scholars to discuss Linnean manuscripts and

printed works extant in the Hagströmer collections.

Photo: Letter from Carl Linnaeus to Abraham Bäck, 13 November 1761 (KIB MS 27:119).

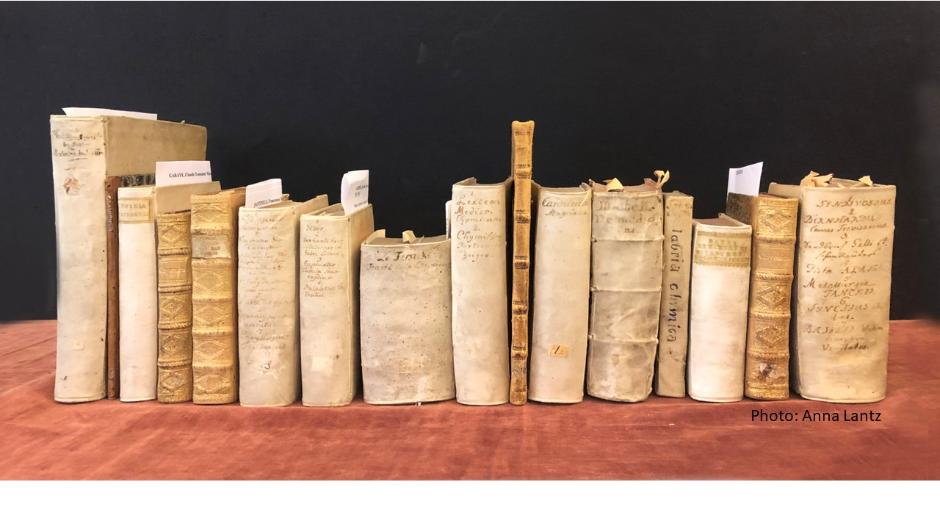

Season´s Greetings!

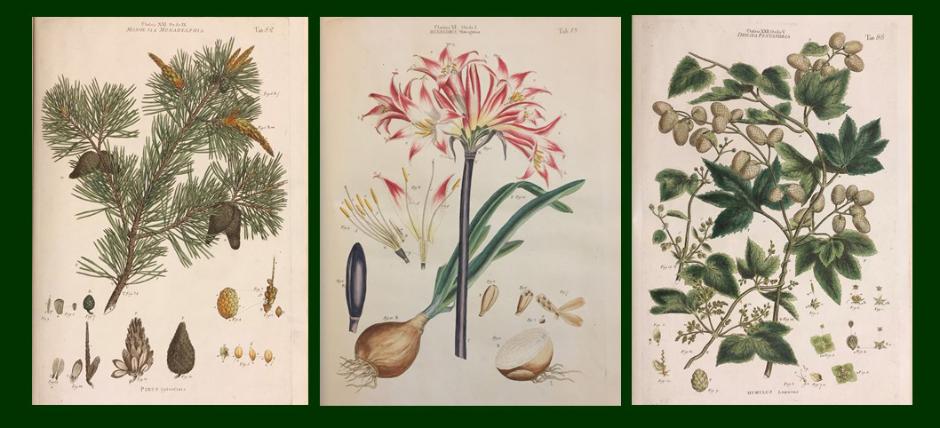

A beautiful selection of books from our collections!

Art at the Hagströmer Library 2021!

In 2021, the Hagströmer Library will focus on art and artists. Beginning in the spring with an exhibition of illustrations in books and prints within the library's own collections, featuring some of art history's most famous figures, created by our curator Anna Lantz.

During the autumn, we present new exhibitions in collaboration with two female artists: Jenny Åkerlund and Ida Rödén. Åkerlund's works of glass and paper are based on themes such as optics and ophthalmology. Rödén's work revolves around the fictional Linnaeus disciple Jonas Falck.

Keep an eye out for events and exhibitions in Haga Tingshus and online during the year!

Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden och Honoré Daumier är bara några av de världsberömda konstnärer vars verk ingår i Hagströmerbibliotekets samlingar. Våra samlingar har också inspirerat framstående samtida konstnärer som Ulla Wiggen, Helene Schmitz, Nikolina Ställborn, Uriel Orlow och David Molander..

2021 riktar Hagströmerbiblioteket fokus på konsten och konstnärerna. Vi inleder under våren med en utställning som visar illustrationer i böcker och grafiska blad ur bibliotekets egna samlingar, av några av konsthistoriens mest kända gestalter, skapad av vår curator Anna Lantz.

Under hösten presenterar vi nya utställningar i samarbete med två kvinnliga konstnärer: Jenny Åkerlund och Ida Rödén. Åkerlunds verk av glas och papper baseras på teman som optik och oftalmologi. Rödéns arbeten kretsar kring den fiktive Linnélärjungen Jonas Falck..

Håll utkik efter evenemang och utställningar i Haga Tingshus och online under året!

God Jul och Gott Nytt År!

Season´s Greetings and Best Wishes for the New Year!

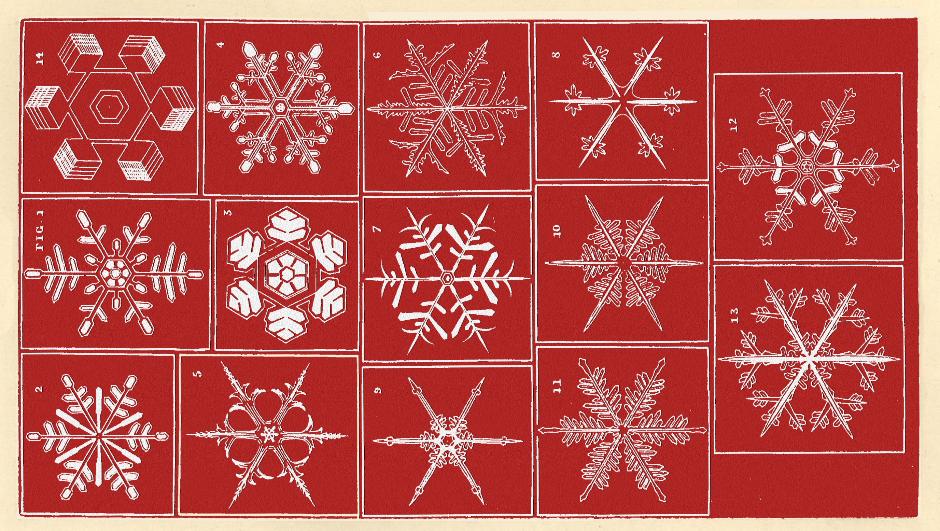

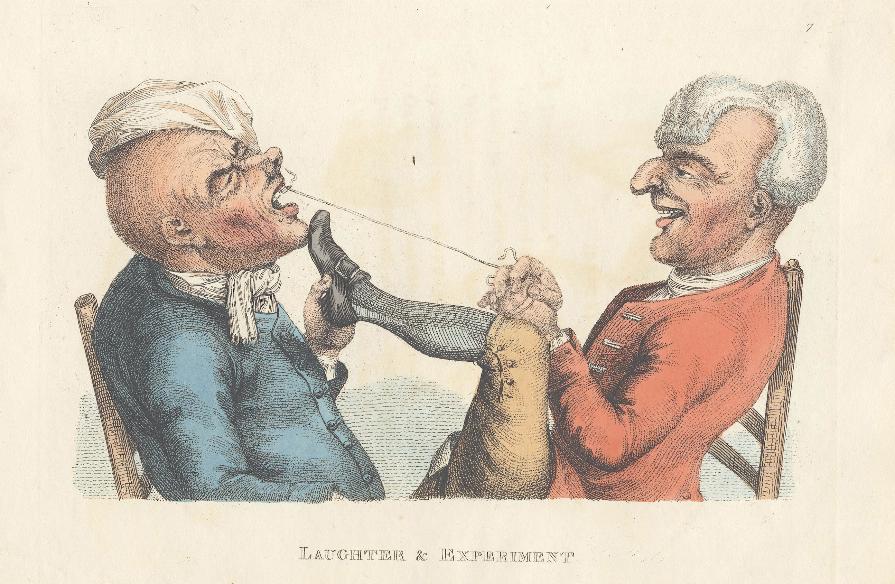

Snow Crystals. Lionel S. Beale, How to work with the microscope (London 1868). Hagströmer Library, Karolinska Institutet.

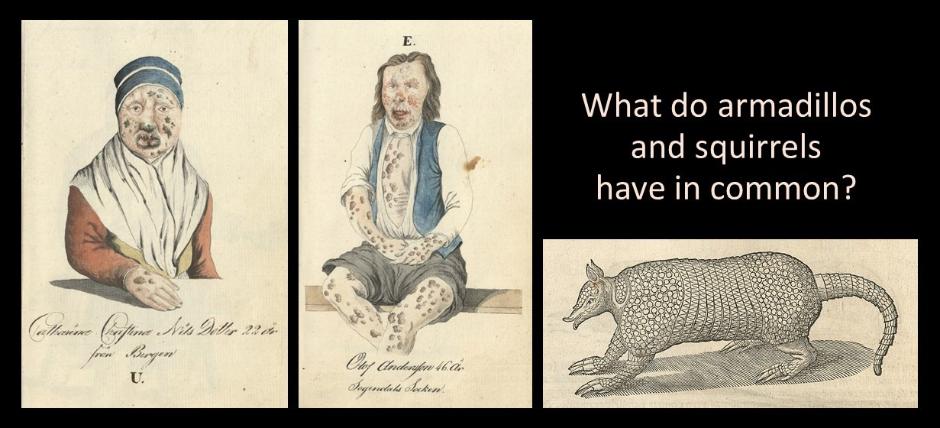

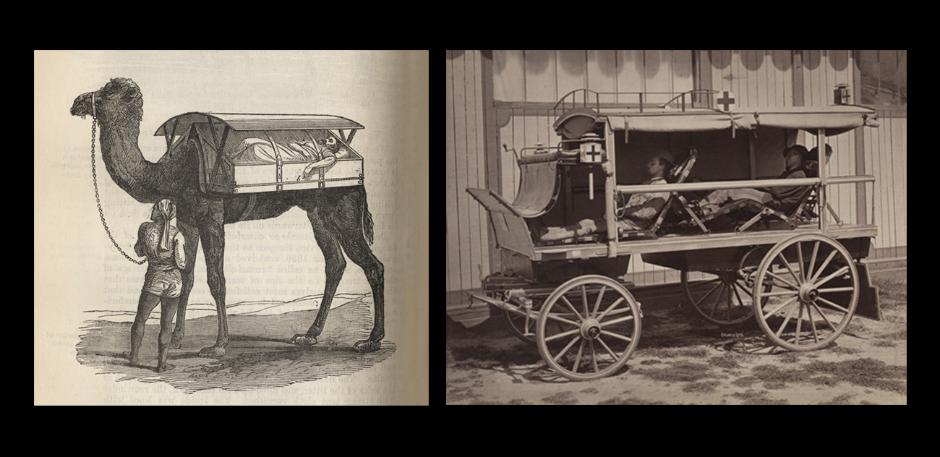

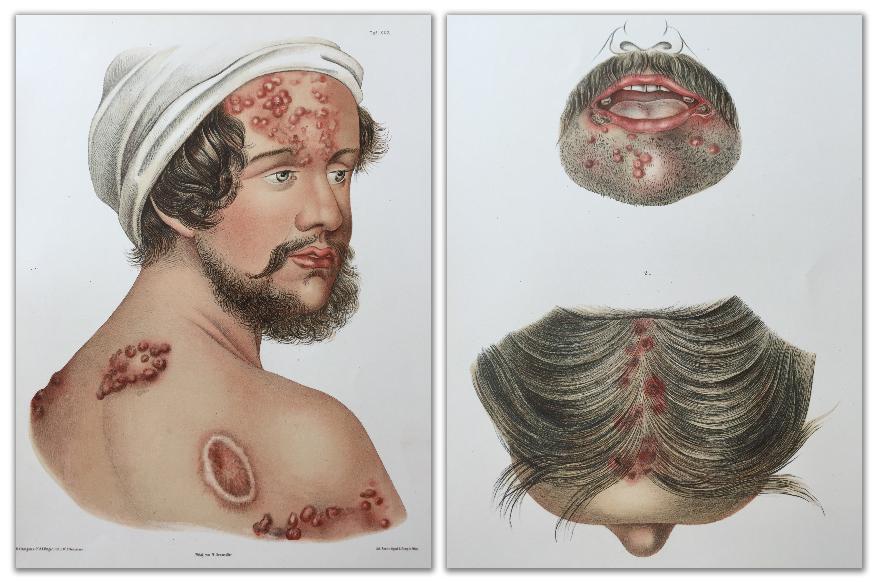

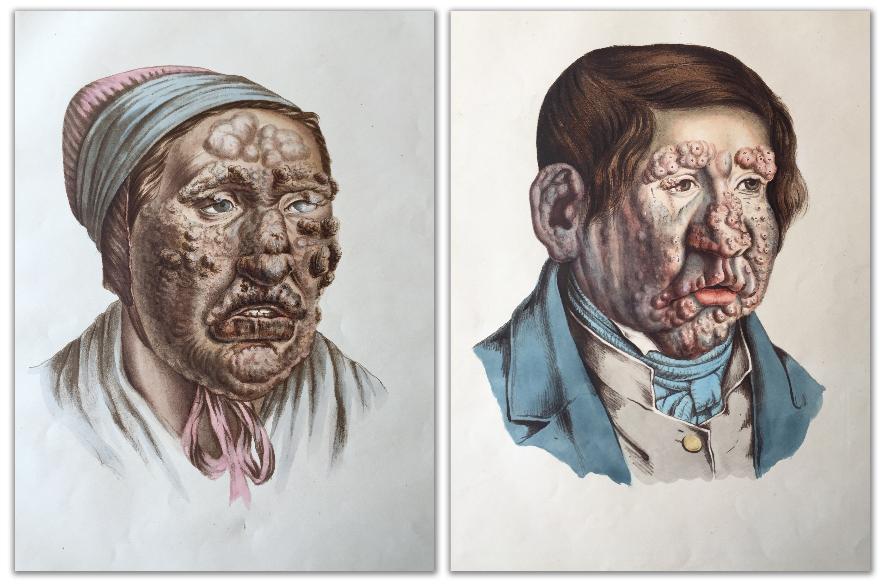

What do armadillos and squirrels have in common?

Over the past year, we have learned of the possible consequences of eating or having close contact with exotic animals like pangolins and bats. New viruses and bacteria can develop and spread at food markets when animals and meat are handled carelessly. Leprosy is a specific infectious disease that is often thought to be a thing of the past, but mycobacterium leprosa is a bacteria that still exists in many countries and that spreads through both zoonotic and anthroponitic processes (i.e. from animals to humans or vice versa). What is less well-known is that, apart from certain species of ape, armadillos and squirrels also carry the bacteria and become sick. If you want to read more about leprosy, I refer you to my blog entry of 4 May 2016.

The armadillo – certainly not man’s best friend

You could say that the leprosy bacteria has found the perfect host in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). The animal has a long lifespan, a low body temperature and lives close to human habitation. While it is not found in Europe, it is common in Central and South America. Scientists believe that humans once infected the animal and now it is returning the infection through a variety of routes. These animals are used as pets (for racing) but can also end up on barbecues due to their tasty meat after having been shot and run over. They are nocturnal and in the USA are called “Mexican road-bumps”. The infection risk has been known about since the 1970s, although it seems no one quite realised just how common it is for people to be infected. When the spread of the disease and the habitation of the animal were compared, there was a considerable geographical overlap in the graphs. Awareness has risen in recent years.

Social worker José Ramirez lives and works in Mexico and has written a book about the many years of suffering he endured after contracting leprosy, an unlikely diagnosis that was not established until the end of the 1960s – 7 years after onset. From that point on he spent many years at Carville leprosy hospital, which was effectively a leper colony. The doctors there were sceptical about his having leprosy since he had not travelled to the countries where the disease was endemic. The most likely disease vector was an armadillo. Different medicines were still being tested at this time, and powerful painkillers often had severe side-effects. One such that made it into production was the drug Thalidomide, which led to serious birth defects when taken by pregnant women. The treatment has improved over the years, but driving the bacteria from the body was once a long and arduous process, which, for the unlucky, caused severe harm before taking effect. This is still the case in many developing countries, where sufferers can sustain damage to the nerves, skin and, eventually, the bone. These days, combination preparations are used involving different types of antibiotics to achieve greater efficacy and avoid resistance. After many years of treatment José Ramirez recovered largely unscathed, since which time he has devoted his professional life to informing people about leprosy and supporting sufferers.

Professor Stewart Cole has worked at Institut Pasteur for many years and in 2007 was made professor and director of the international health and research body Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne. As some of the leading leprosy researchers of today, he and his team have used advanced DNA techniques and molecular-biological research to map the bacteria and categorise 154 strains from around the world.

The poor red squirrel

A few years ago, National Trust researchers in the UK found that the population of red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) on the British Isles have leprosy. After researching its genome, they concluded that it is a mediaeval variant of the bacteria that produces similar symptoms as those seen in humans: lumps, growths, patchy skin, etc. The squirrels lose the tufts of hair on their ears. Since squirrels were used for food (their meat is said to resemble chicken) and for their fur, there was once much more contact between us and them. Today, however, the species is protected and almost extinct, which is also a consequence of having been out-competed by the invasive North American grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). It is no longer common for squirrels to infect humans.

The beneficence of J.E.Welhaven

For his entire working life at St Jörgen’s leprosy hospital in Bergen, priest Johan Ernst Welhaven (1775 - 1828) did his best to care and make life easier for the seriously ill patients there. Apart from curing their souls, the much beloved priest collected clothes, food and medicine, which he distributed to the sick. This gave him good insight into healthcare and enabled him to get to know the patients, about whom he also made careful notes. It is not inconceivable that life-long hospitalisation awaited the incurably sick, who often lived for a fairly long time. Many of these hospitals also served as poor houses and medical institutions for the multimorbid and elderly. In the Middle Ages, Landskrona once boasted such a hospital – effectively a Swedish House of the Holy Spirit (a kind of hospital prevalent in mediaeval Europe) – but towards the end it mostly took care of other patients than those with leprosy. The Hagströmer Library holds a book containing unique hand-coloured drawings of 32 patients from the leprosy hospital in Bergen, probably drawn by Welhaven himself.

Readers interested in interdisciplinary subjects concerning veterinary versus human medicine and medical history can find out more in the anthology Humanimalt, published in 2020. This is one of a series of three books from Exempla publishers, the others being Främmande Nära and InomUtom, which are due for publication next spring and autumn respectively.

Ann Gustavsson, 15 October 2020

Illustrations:

Armadillo. From Willem Piso & Georg Marggraf & Johannes De Laet: Historia naturalis Brasiliae. Leiden & Amsterdam (1648). Hagströmer Library.

Drawings of patients. From Johan Ernst Welhaven: Beskrifning öfver de spetälske i S:t Jörgens hospital i staden Bergen i Norrige (1816). Hagströmer Library.

References:

Avanzi, Charlotte (2016) Red squirrels in the British Isles are infected with leprosy bacilli, Science 11/11.

Avanzi, Charlotte (2018) Genomics: a Swiss army knife to fight leprosy. Thèse No 8482. Lausanne: La faculté de sciences de la vie.

Gustavsson, Ann (2005 - 2006). Landskrona hospital. Leprahospital eller fattighus? Master’s dissertation in osteoarchaeology, Stockholm University.

Ramirez, José P. (2009) Squint. My Journey with Leprosy. Mississippi: The University Press of Mississippi.

Learn more: Professor Stewart Cole giving a talk, listen here!

Ann Gustavsson is an archivist/curator at Karolinska Institutet’s Medical History and Heritage Unit. She has a master’s degree in archaeology and another in osteoarcheology. With a background in cultural studies, she went on to read ancient history and archival science. Her speciality is pathological lesions in bone. Ms Gustavsson is currently inventorying, analysing and digitizing Karolinska Institutet’s anatomical skull collection.

Translation: Neil Betteridge

HAGSTRÖMER LIBRARY ONLINE AND VIDEO LINK TOURS

Hagströmer Library's catalogue online. From Autumn 2020, our catalogue is available via the Hagströmer Library's website, where you will also find our virtual book museum. Please visit our catalogue and virtual museum here!

Mini tours of the Hagströmer Library on KI's youtube channel. View our mini tours by clicking here and then on the playlist Karolinska Institutet Medical History and Heritage. Or search for ‘Hagströmer Library’ on Youtube.

Library tours via video link. From Autumn 2020, we offer library tours via video link (zoom or teams). The price for this is the same as for regular viewings.

Responses to our live online tours:

"We have received a completely positive response to the tour of the Hagströmer"

Charlotta Forss, organizer of the workshop Health and Society in Early Modern Europe, Stockholm University, June 10, 2020.

Love it! "It's like a Dogma movie."

Participant of tour for the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, October 5, 2020.

BOOK AND VISIT THE HAGSTRÖMER LIBRARY

After being closed during the spring, the Hagströmer Library has opened for certain public activities during the autumn of 2020, of course observing the prevailing infection control recommendations. We offer face masks, disposable gloves and hand sanitizer to all visitors. All bookings are made via: hagstromerlibrary@ki.se

Library viewings in Tingshuset. During the autumn, we accept a limited number of pre-booked groups of up to a maximum of 10 people. Contact us for information.

Reading room opening hours. During the autumn of 2020, the reading room is only open for pre-arranged visits. We want to advise that we may have to say no to visitors on occasion as the space in the reading room is limited.

Booking of conference rooms in Haga Tingshus. Groups from Karolinska Institutet can, as usual, book floor 4 for workshops or mini-conferences to the extent that we have staff who can receive and see out. However, the number of participants is limited to 10 because there are limitiations in the house that make it impossible for larger groups to keep sufficient distances.

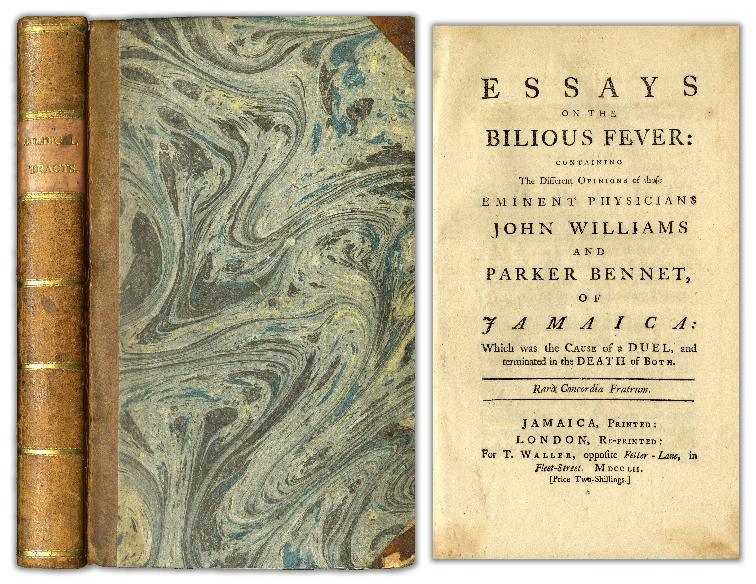

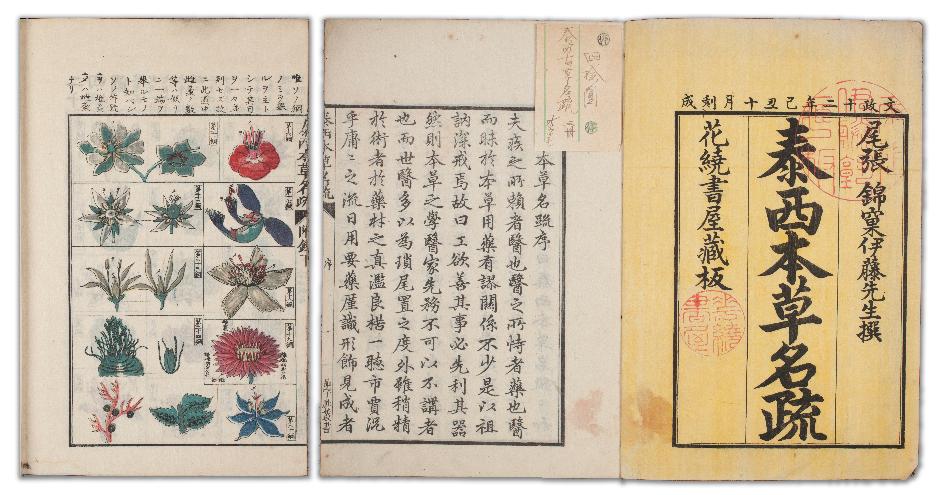

Exhibitions in the Library. This spring's standing exhibition with rare books in botany, pharmacy art and surgery selected by Ove Hagelin will remain during the autumn.

Lectures and Presentations. No public lectures will be held in Haga Tingshus during Autumn 2020.

Summer greetings from Hagströmerbiblioteket!

It is summer once more. During this very strange spring we have been forced to cancel

lectures, guided tours, the open reading room hours and much more. But let us

focus on the positive. The restrictions of our public activities have given us

more time to work with our collections. We have also taken the opportunity to

restore and paint the windows and door facing the motorway, take a look if you

happen to drive by

Come

September, something important will happen. We will make our library catalogue

with more than 45000 entries available online on the Hagströmer library

website. In cooperation with Karolinska Institutets Bibliotek we will, later

during the autumn, make several thousands of books searchable through Libris,

the national Swedish library database.

There will be more exciting

news from the library later in the autumn as well, and we hope to resume part

of our usual public activities. In fact, already a few months ago we started to

receive researchers by appointment only. In August we hope to be able to resume

our guided tours and open the reading room for visitors. Welcome back

after the summer!

Glad sommar önskar Hagströmerbiblioteket!

Det är nu sommar igen efter en märklig vår. Föreläsningar,

visningar, den öppna läsesalen och forskarbesök, allt har vi behövt ställa in.

Men för att fokusera på det positiva. Begränsningen av vår utåtriktade

verksamhet har gett oss tid att ägna tid åt arbete med samlingarna. Under våren har vi också passat på att få

alla fönster mot motorvägen målade. Passa på att kika om ni kör förbi!

En stor nyhet kommer att lanseras i september. Vi kommer att tillgängliggöra vår bibliotekskatalog

med mer än 45000 poster online via Hagströmerbibliotekets hemsida. I samarbete

med KIB kommer vi också troligen senare under hösten att göra flera tusen

böcker sökbara via Sveriges nationella biblioteksdatabas Libris.

Fler spännande nyheter kommer att avslöjas i höst, och även

den vanliga verksamheten hoppas vi kunna återuppta, åtminstone del. Redan i maj

smygöppnade vi för i förväg avtalade forskarbesök. I augusti hoppas vi kunna

starta visningar för små grupper igen, och öppna läsesalen, om än inte i full

skala. Välkomna tillbaka efter sommaren!

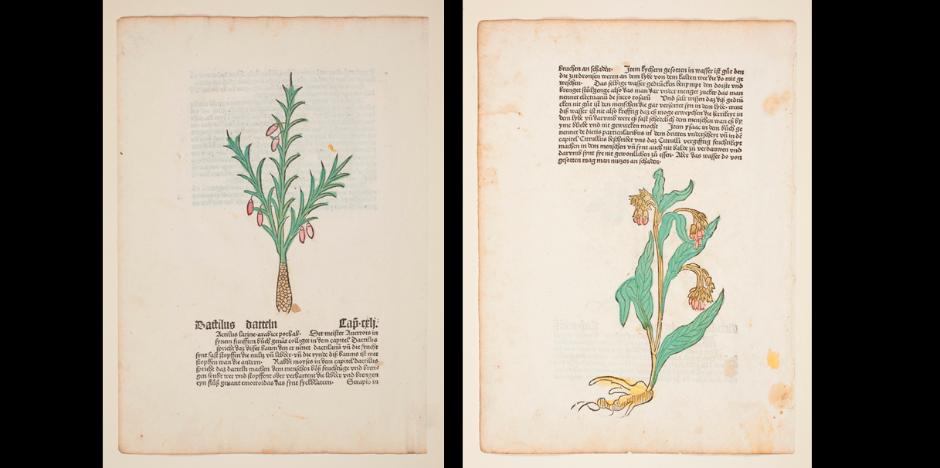

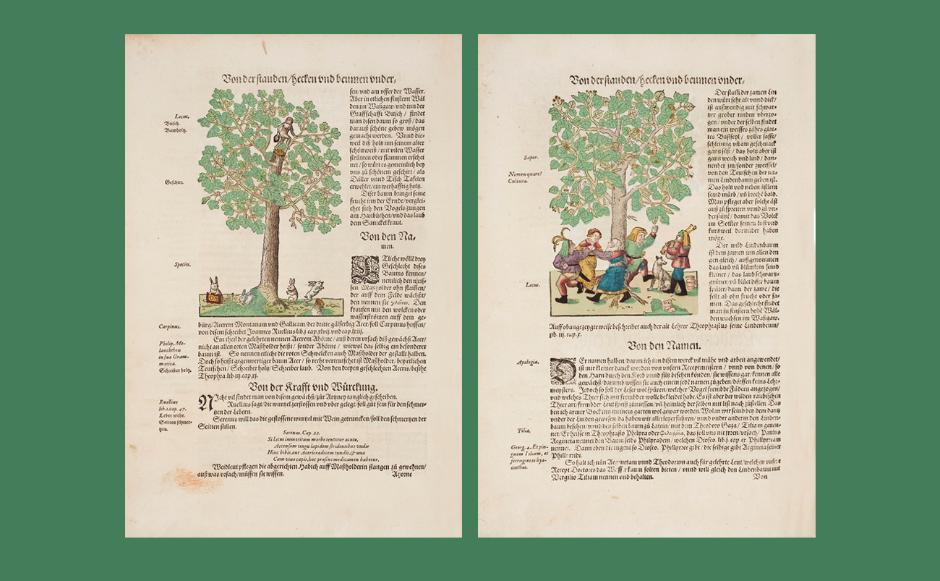

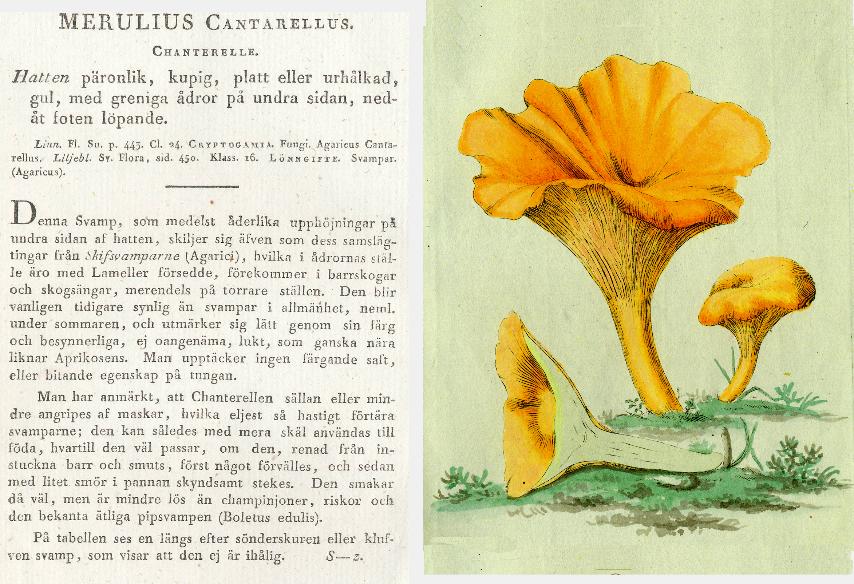

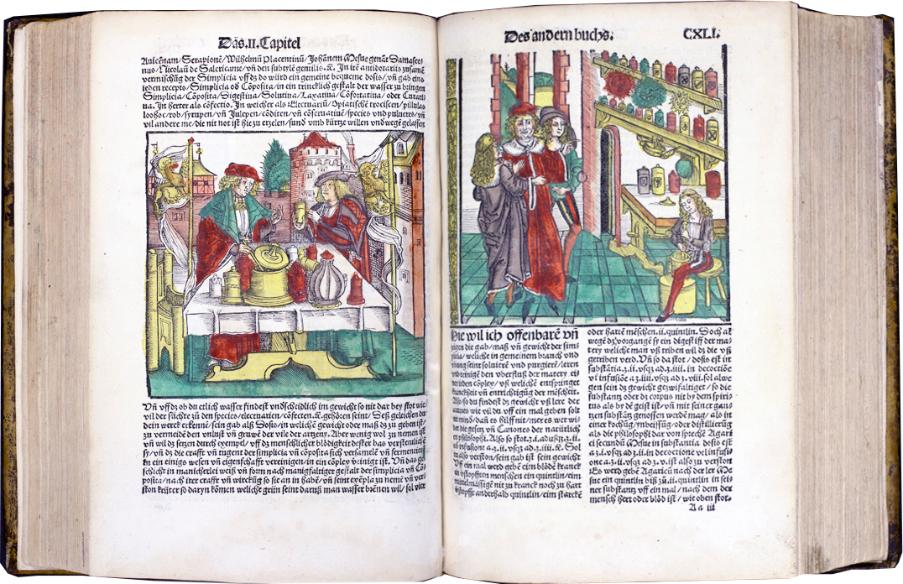

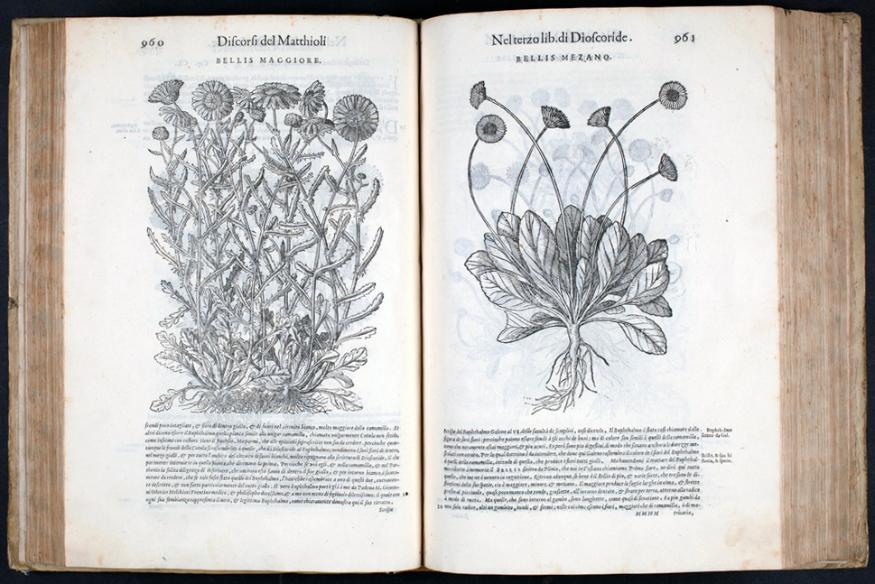

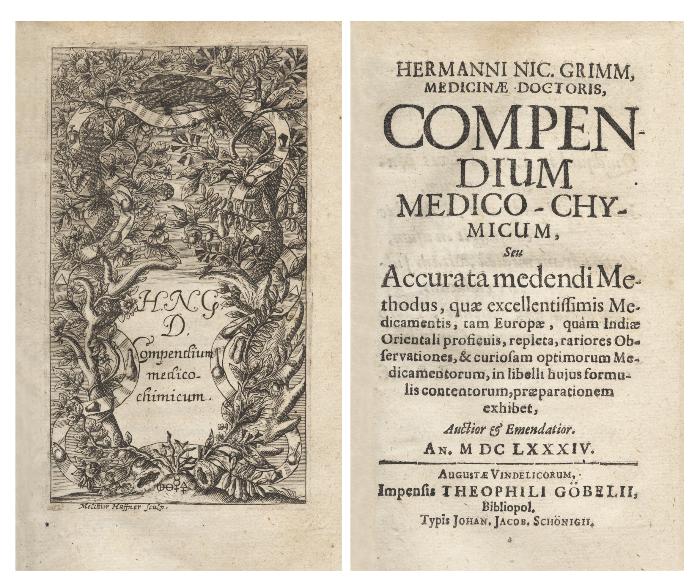

New Kreüterbuch, Leonhard Fuchs (Basel, 1543).

Kreutterbuch, Hieronymus Bock (Strassburg, 1580).

Kreutterbuch, Hieronymus Bock (Strassburg, 1580).

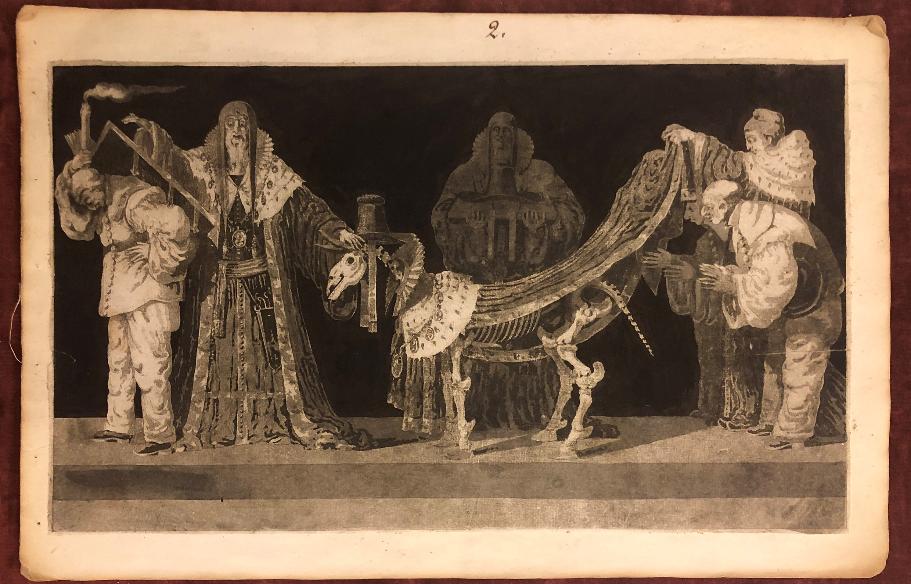

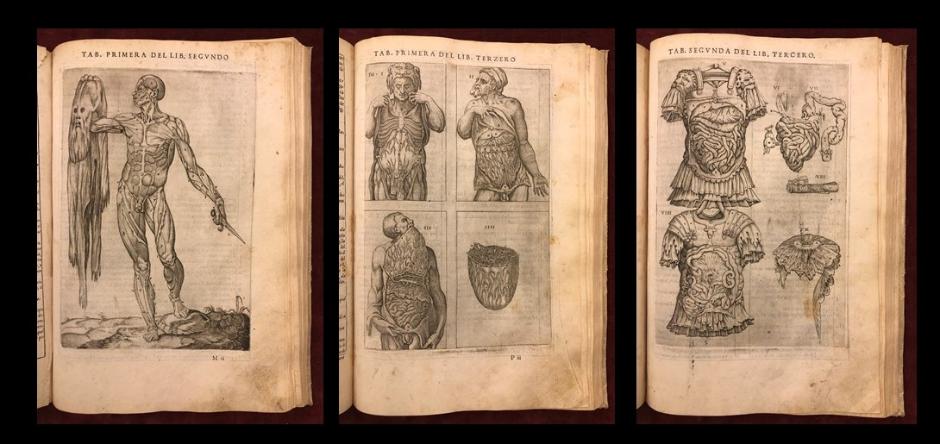

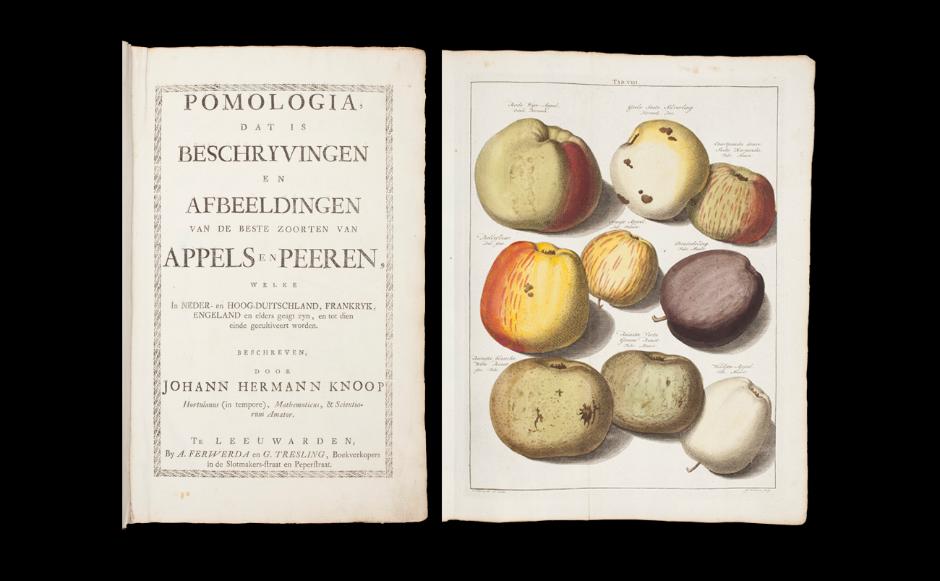

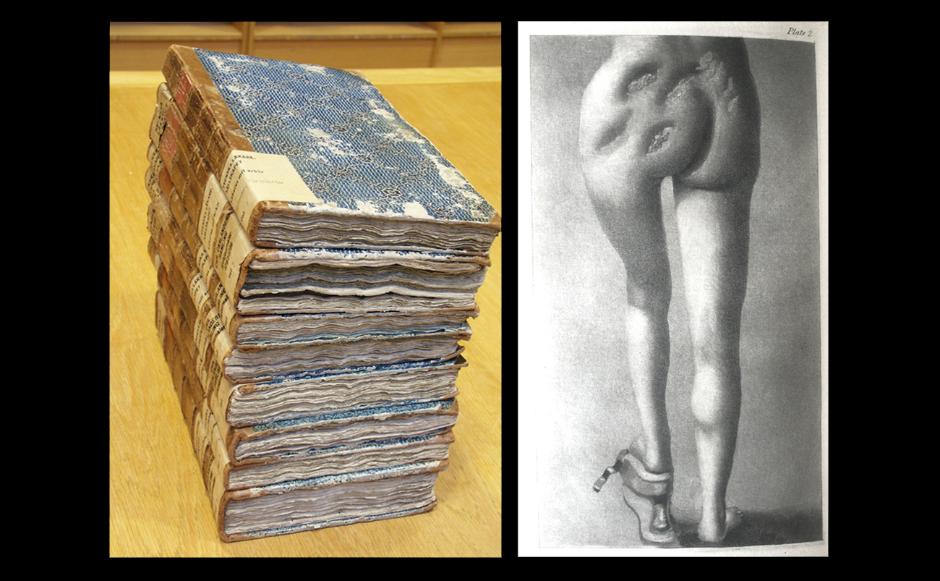

Juan de Valverde and his anatomical atlas

Juan de Valverde´s (ca 1525 -ca 1587) anatomical atlas Historia de la composicion del cuerpo humano first printed in 1556 was one of the most popular and widely read anatomical books during the sixteenth century. It was issued in more than ten editions in Spanish, Italian, Latin, and Dutch, being an indication of it´s great popularity. The Hagströmer Library is fortunate to have a total of four copies, the rare first edition of 1556 and three later editions printed in 1579, 1586, and 1589. This blog will briefly present Valverde and his anatomical book, focusing on some of the fascinating illustrations in the first edition, which featured copper plates that were later re-engraved or copied in all the later editions and in other books as well.

Very little is known of Valverde´s life. He was born in Amusco, a small village in the province of Palencia in Northern Spain and studied philosophy and the humanities at the university in either Valladolid or Palencia. After graduation he continued his studies abroad like many other young students at the time. In 1541 he arrived in Padua in Northern Italy where one of the best medical universities in Europe was located and where Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) taught anatomy. Valverde´s first year there is largely unknown, but he probably studied under both Vesalius and Realdo Colombo (c. 1515-1559) who was appointed to the second Chair of Surgery there. The meeting of Columbo and Valverde had a decisive impact on Valverde´s future success. During the following years he followed Columbo first to Pisa where Columbo was appointed to the Chair in anatomy and Valverde worked as his assistant, and then in 1548 they travelled to Rome where Valverde´s career continued to flourish. By 1555 he was teaching medicine in the Hospital of Santo Spirito and when St Ignatius of Loyola, co-founder of the Jesuit order and who later was canonized died in 1556, Valverde performed the autopsy. His medical prestige within Vatican circles was high and he became physician to Cardinal Juan Alvarez de Toledo, Archbishop of Santiago and first General Inquisitor of Rome, to whom Valverde also dedicated his book in 1556.

Historia de la composicion del cuerpo humano was printed in Spanish by Antonio Salamanca and Antonio Lafrery in Rome 1556. It contains forty-two full-page engravings depicting skeletons, muscle manikins and different body parts. The drawings were made by Gaspar Becerra (1520-1570), a Spanish architect, sculptor, painter, and anatomist who worked with Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, and the engravings were made by Nicolas Beatrizet (1515- ca 1589), a Frenchman who came to Rome in order to study the great works by Raphael, Michelangelo and others. Most of the illustrations in Valverde´s book are copied from the woodcuts in Vesalius´s famous Fabrica of 1543, as the muscle manikins, skeletons, and brains, which were copied in many anatomical books for centuries due to their high artistic quality and great popularity. Valverde writes in the foreword:

Although it seemd to some of my friends that I should make new illustrations without using those of Vesalius, I did not do so in order to avoid the confusion that could follow, not knowing clearly in what I agree or in what I disagree with him, and because his illustrations are so well done it would look like envy or malignity not to take advantage of them. Mainly becau- se it has been so easy for me to improve them as it shall be difficult for any other who would like to depart from them to make them that good.

One of the new illustrations, i.e. not copied from the Fabrica, is the spectacular échorché figure of a man holding his own skin in one hand and a knife in the other. The image is clearly influenced by the figure of St Bartholomew in Michelangelo´s fresco The Last Judgement from 1536-1541 in the Sistine Chapel in Rome, where Becerra worked as his assistant. St Bartholomew was a Christian saint who according to legend was skinned alive and then beheaded, and therefor often depicted holding the attributes of his martyrdom, the skin and a knife in his hands. The facial features in the skin, both in the engraving and in the fresco are by some said to bear the features of Michelangelo himself. The fresco was one of the most famous artworks in Europe at the time and certainly both Valverde and Becerra were aware of that many readers would recognize the affiliation between the two figures. Other new and striking images are the three men who seem fully content to display the inside of their abdomen, while curiously looking at each other. The top left figure is wearing a lion skin reminiscent of Hercules dressed in the Nemean lion´s skin, one of the many gods from Greek mythology popular in Baroque art. Maybe equally interesting are the odd images depicting figures in roman(?) armours opened at the stomach revealing the intestines of the bearer.

For all interested in the technique and craftmanship of these engravings, it is a wonderful and most interesting experience to put the five books next to each other, Vesalius´s Fabrica of 1543 and the four editions of Valverde´s book in order to carefully study the images side by side.

To see more images from Valverde´s book click here!

Anna Lantz, 29 May 2020

References

Choulant, Ludwig, History and Bibliography of Anatomic Illustration (New York and London, 1945).

Clair, Colin, Christopher Plantin (London, 1960).

Cushing, Harvey, A Bio-Bibliography of Andreas Vesalius (New York, 1943).

Guerra, Fransisco, ‘Juan Valverde de Amusco’, Clio medica, 2 (1967).

Okholm Skaarup, Bjørn, Anatomy and Anatomists in Early Modern Spain (London and New York, 2015)

Ocular fundus

Chromolithograph. Eduard von Jaeger, Beiträge zur Pathologie des Auges. Mit Abbildungen in Farbendruck, Wien, 1855-56.

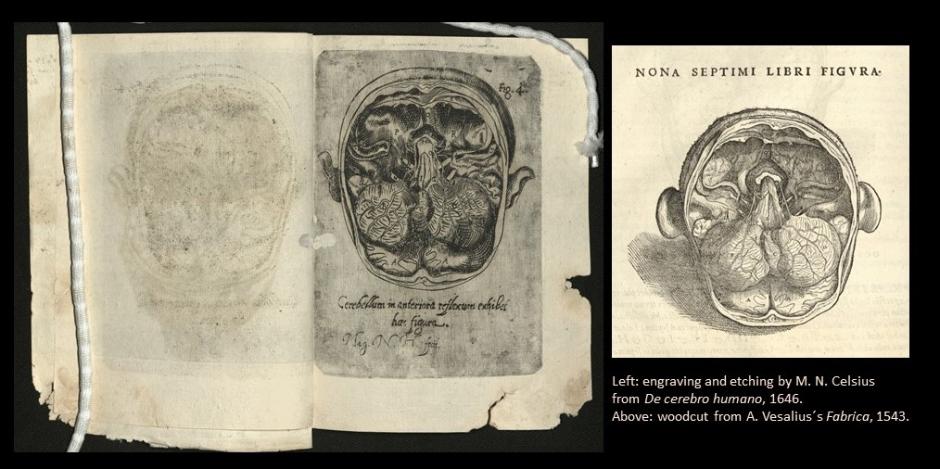

Magnus Celsius and his Anatomical Engravings

The first dissertation printed in Sweden illustrated with engravings is De cerebro humano printed in 1646. It is a small dissertation in quarto format of only sixteen pages illustrated with four engravings depicting the human brain. The first plate is signed in Latin `Magnus N. Helsing fecit´ giving us a clue to the artist´s identity, Magnus Nicolaus Celsius. He was a skilled engraver who later would illustrate three more dissertations and one treatise. Since a full discussion of all his engravings in these works would require a rather long text, the aim of this blog post is to give a short presentation of Celsius himself and of his engravings in De cerebro humano of 1646.

Magnus Nicolaus Celsius (1621-1679) was a Swedish mathematician, astronomer, and botanist, a versatile polymath active at Uppsala University during most of his life. He was the first of many in the Celsius family to become a scientist. Two of his sons were professors at Uppsala University and he was the grandfather of Anders Celsius who proposed the Celsius temperature scale, and there were others as well. After several years of studies at the university he became lecturer in 1655, and after being extraordinary professor for some years he became ordinary professor of mathematics in 1668, and between 1674 and 1675 he served as rector. Two years later he was ordained a priest and became a vicar in Old Uppsala before he passed away in 1679. Today Celsius is foremost known for deciphering the Hälsinge runes in the 1670s.

Celsius work as an engraver is one of his lesser known activities. Only a few engravings by him are known today and they were all made between 1646 and 1661 as illustrations in the four dissertations and the treatise mentioned above, printed at Uppsala University. Where he learned to engrave and where the impulse to do so might have come from is unknown, although he also made his own mathematical and astronomical instruments, suggesting a wider interest and skill for metalwork. There were others making engravings for dissertations at the university in the seventeenth century as well, but all of them except one are printed between the late 1660s and 1690s, several years after Celsius made his last engraving.

De cerebro humano was his third dissertation as a student at the university, where he enrolled in 1641. His uncle Olaus Unonius, professor of logics and metaphysics, was praeses and could preside over a dissertation in anatomy, here the human brain. As mentioned above it has a total of sixteen pages of text and four illustrations. The first four pages constitute the title and the dedication, followed by eleven pages of text ending with gratulations to the young student on the last page. There are different opinions regarding who wrote the dissertation, but we do know that Celsius made the engravings. Two of the images are full page engravings while the other two are smaller and fitted onto one and the same plate. Besides being the first known engravings Celsius did and the first engravings in a dissertation in Sweden, they are also the first illustrations in an anatomical dissertation in the country.

A study of the engravings and their relation to the text is very interesting, since it reveals that Celsius is firmly working within the established tradition of anatomical illustration dating back to Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) and his revolutionary work Fabrica of 1543, whose illustrations influenced later anatomical works for centuries. This is evident in that all four figures, besides being numbered all have small key letters referring to the text where that specific part is discussed and marked by the same letter, and also in that all the figures themselves derive from images in the Fabrica. Either Celsius had direct access to the great work, or more likely to one of the many anatomical books where Vesalius´s woodcuts were copied, maybe held in the university library or in one of the professors´ private libraries.

Of further note is that Celsius has engraved his own name on two of the plates, `Magnus N. Helsing fecit´ on the first plate, and `Mag. N. H. fecit´ on the last plate, at the time his name was Helsingius but later he would change it to Celsius. There is no reason not to assume that Celsius engraved all three plates himself even though he did not sign his name on the second plate. A closer examination reveals that Celsius´s figures in these three plates, as well as the later ones, often are made by a combination of line engraving and etching.

De cerebro humano is known in only a few copies in Sweden, of which some are held at the Hagströmer Library, the National Library of Sweden, and the Uppsala University Library.

Anna Lantz, 1 May 2020

Links:

View all the images discussed in this text: here

Primary sources

Unonius, Olaus, Disputatio physica de cerebro humano, quam ... sub clypeo ... Olai Unonij Gev. ... publicè defendendam proponit Magnus Nicolai Helsingus ... ad diem 16 decembris in audit. vet. maj. horis consvetis (Upsaliæ: imprimebat Eschillus Matthiæ, anno 1646)

Vesalius, Andreas, Andreae Vesalii Brvxellensis, scholae medicorum Patauinæ professoris, de humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Basileae: ex officina Ioannis Oporini, anno salutis reparatae M D XLIII. Mense Iunio, 1543)

Secondary sources

Annerstedt, Claes, Upsala universitets historia D. 1 1477-1654 (Uppsala: Universitetet, 1877)

Annerstedt, Claes, Upsala universitets historia. D. 2, 1655-1718, 2 vols (Uppsala: Universitetet, 1909)

Lidén, Johan Hinric, Catalogus disputationum, in academiis et gymnasiis Sveciæ, atque etiam, a Svecis, extra patriam habitarum, quotquot huc usque reperiri potuerunt; collectore Joh. Henr. Lidén, sectio I-V (Upsala, 1778-1790)

Meijer, Bernard and others eds., Nordisk familjebok, 38 vols (Stockholm: Nordisk familjeboks förlag, 1904 - 1926), IV (1905)

ANNA LANTZ, MA, curator of rare books and prints at the Hagströmer Library is an art historian and book historian specialising in early modern medical illustrations and printmaking techniques.

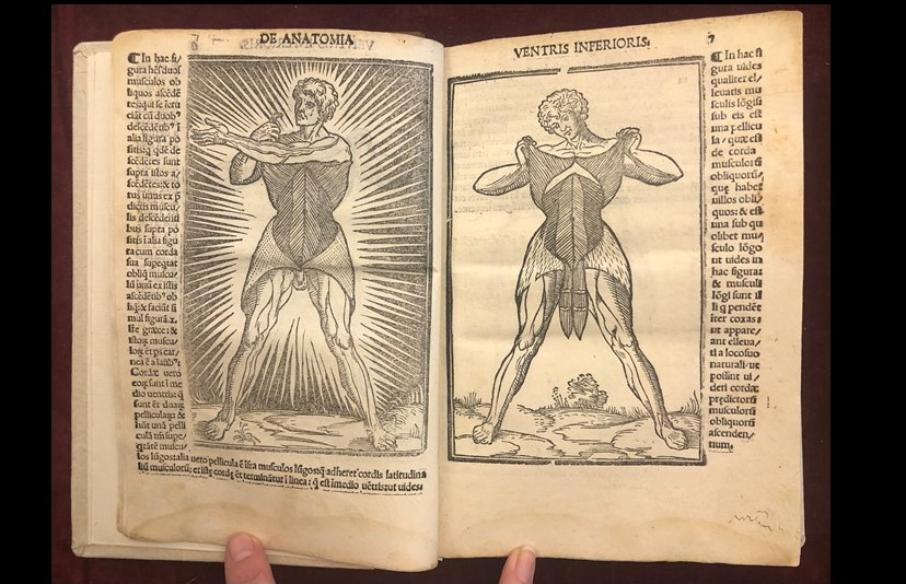

Berengario da Carpi in the Hagströmer Library!

One of the very rare books in the Hagströmer Library is Isagoge breves printed in 1522, known in less than ten copies in the world. Two of these are to be found in Sweden at the Hagströmer Library and at the university library in Uppsala as part of the Waller collection. It is a descriptive anatomy and a manual on how to dissect the human body illustrated with woodcuts, presenting the most comprehensive and independent understanding of human anatomy at the time. The author is Jacopo Berengario da Carpi (ca 1460- ca 1530), one of the most important Italian anatomists before Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) and Isagoge breves is one of his best known works and a great scientific achievement.

Berengario´s life

Berengario grew up in Carpi in the region of Emilia Romagna in Northern Italy where his father was a barber-surgeon. He spent his youth in the company of Alberto Pio, son of the Lord of Carpi and they had the same teacher in Aldus Manutius, the great humanist printer, who lived and taught there in the 1470s. Berengario probably never went to medical school before going to Bologna for his doctorate in the 1480s, instead he learned both anatomy and dissecting from his father and his own practical experience. In 1489 he received his degree in Bologna, and the years directly thereafter are quite unknown. Because of political events and the troubled history in the area he probably had access to plenty of dead and wounded bodies to dissect and practice anatomy on and gained medical success by his skill in surgery and practical medicine. In 1502 he became Lecturer in surgery in Bologna, a position he held until 1527 and when the plague broke out there in 1508 Berengario was also appointed what today would be called Commissioner of Health in order to fight the plague.

He had a large clientele and built himself a fortune as physician to the rich and powerful in Bologna and the surrounding areas. In 1516 he bought a palazzo where he held his art collection which included a roman torso, a painting by Raphael, works by Benvenuto Cellini, and others. Around this time Berengario was called to Florence by the pope Leo X to treat one of his friends there and he also successfully treated the pope´s nephew Lorenzo de Medici, Duke of Urbino, for an injury to the head. Later in 1526 Berengario spent some time in Rome on the request of another pope, Clement VII in order to treat people suffering from syphilis, using mercury(!). Cellini, who met him there writes: “a very shrewed person he was, too, he did wisely in leaving Rome; for not many months after, all those whom he had treated were a hundred times worse than before, and he would have been killed had he stopped”. Cellini also complains that Berengario was expensive and charged his clientele huge amounts for his service. Altogether he seems to have been quarrelsome and ferocious, sometimes threatened by severe punishment and even death, but his influential friends usually saved him. When he died in Ferrara around the year 1530 he was a wealthy man known all over Italy.

Isagoge breves of 1522

The main source for anatomical knowledge in the early 16th century were the writings of Galen who were active in the 2nd century AD, and whose works had dominated anatomical knowledge and learning ever since. His texts were used at universities all over Europe and their authority were never disputed nor contradicted. Berengario who knew them well and published several books on anatomy himself often referred to Galen in his texts, one of them being Isagoge breves. Isagoge breves is an instruction book in anatomy and dissection, a manual for students, with extremely detailed information on the anatomy of the entire human body, as he knew it. In this work Berengario is among the first to trust his own scientific inquiry and thereby putting some of the authority of Galen´s texts into question. Furthermore the illustrations were the most comprehensive attempt of making anatomical images from nature instead of the traditional schematic figures. Some even claim his anatomical figures to be the first ever made drawn from nature. He writes himself that a good anatomist “does not believe anything in his discipline simply because of the spoken or written word: what is required here is sight and touch.”. At the time he had the most independent knowledge and accurate scientific understanding of the human anatomy and Isagoge breves was an important contribution to the development of modern anatomy. Immediately after it was printed it became the most authoritative book on the subject before Andreas Vesalius´ Fabrica of 1543, a truly remarkable achievement.

The title page has a beautiful floral border and as in many books at the time both the colophon and the printers mark are found at the very end of the book. In total there are nineteen full page and two smaller anatomical woodcuts in the book and only a few of them will be briefly discussed here. The majority of the illustrations depicts muscle manikins, all together nine images. These figures are all placed in front of a landscape background making an aesthetically bold and graphic statement. The second manikin is the most dramatic with its strong rays of light in a dark sky behind the figure. Another noticeable manikin is holding a rope in his hand, maybe indicating that ropes were often used for suspending the corpse for muscle studying, and that most of the corpses used by anatomist were from dead criminals executed by hanging.

There are two images of skeletons in the book. One is depicted seen from the front with picturesque houses and trees in the background, seemingly smiling and in movement with the arms moving from side to side. The other skeleton is depicted from the back standing in front of grave (?) surrounded with rocks and shrubberies with a town at the horizon, holding one skull in each hand as if juggling. In effect the three skulls in this image are all depicted from different angles, whereby both the top, back, and side of the skull is shown. These two skeletons with their vivid and lively appearance might be based on to the iconography of the dance of death, which was a well-known motif with a long tradition in Italian art, and in other parts of Europe as well. The other illustrations in the book depict arms, legs, and the female reproductive organs among other things. The artists name is unknown, but several names has been suggested. Regardless who the artist was, these illustrations had a great impact on later anatomical images such as the famous muscle manikins placed in beautiful landscapes in Vesalius´ Fabrica.

Isagoge breves is a small and portable book of ca 205 x 140 mm, making it easy to carry around and to use, which might be one of the reasons why there are so few copies still in existence today. The first edition of 1522 which has been discussed here was printed in Latin by Benedictus Hectori in Bologna, but several editions were printed thereafter which are also rare. For all who wish to see all the images referred to in this text please visit Friends of Hagströmer Library on Facebook (Hagströmerbibliotekets vänner), for those who wish to study the entire work page by page, the Wellcome Library has digitized their copy of the book, and for those lacking knowledge in Latin there are at least two English translations of Isagoge breves, one made in 1660 and another in 1959. Please see the links and the references below!

Anna Lantz, 23 April 2020

Links

View the images discussed in this text: here

View Isagoge breves online: here

References

Berengario da Carpi, Jacopo, Isagoge breves, perlucide ac uberime, in Anatomia[m] humani Corporis. (Bologna: Benedictus Hectoris, 30 December 1522)

Berengario da Carpi, Jacopo, A short introduction to anatomy (Isagogae breves) Jacopo Berengario da Carpi translated with an introduction and historical notes by L.R. Lind and with anatomical notes by Paul G. Roofe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959)

Carlino, Andrea, books of the body: anatomical ritual and Renaissance learning translated by John Tedeschi and Anne C. Tedeschi (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999)

Choulant, Ludvig, History and bibliography of anatomic illustration by Ludwig Choulant, translated and annotated by Mortimer Frank. Further essays by Fielding H. Garrison, Mortimer Frank [and] Edward C. Streeter, with a new historical essay by Charles Singer, and a bibliography of Mortimer Frank (New York: Schuman's, 1945)

ANNA LANTZ, MA, curator of rare books and prints at the Hagströmer Library is an art historian and book historian specialising in early modern medical illustrations and printmaking techniques.

Spring 2020!

For all of You interested in the Hagströmer Library collections, this spring we will publish blogposts

once a week presenting books and other items from the collections! To receive our Newsletter, please sign up with Your email adress at the top right hand corner on this page (FOLLOW). You can

also follow Friends of the Hagströmer Library on social media, where even more

books will be discussed! Welcome!

Do You have a question for us? Please send us an email: hagstromerlibrary@ki.se

For Friends of the Hagströmer Library on social media, please follow these links:

Anna Lantz, 16 April 2020

Season´s Greetings!

This charming illustration belong to Max Taube´s (1851-1915) Der bunte Hans. Ein Bilderbuch zur Entwickelung des Farbensinnes für Kinder von 1-5 Jahren, and Gezeichnet von Adolf Reinheimer, printed in Leipzig in the 1870´s (?). To view more images from this book, and the cover as well, please visit Friends of the Hagströmer Library´s page on Facebook, press here!

Cancelled!

Due to Covid-19, the activities at the Hagströmer Library are limited during the spring. This means that the lectures on April 27 and May 12 will be moved to the autumn instead and that no guided tours or other public activities will take place until May 15, initially. The reading room is also closed until then. More information about the activities at the library will be announced in due course. For other library services or questions please contact us at: hagstromerlibrary@ki.se or 08-5248 6828

Anna Lantz

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis

In the middle of the 1840s Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (1818-1865) was appointed assistant lecturer at the First Obstetrical Clinic of the Allgemeines Krankenhaus in Vienna. At that time mortality from puerperal sepsis was very high, especially in maternity hospitals. Between the years 1841 and 1843 as many as sixteen percent of the parturient women there died. Semmelweis noticed that those attended by midwifes, as opposed to medical students, had a much lower death rate with an average of only ca. two percent. This led him to surmise, correctly, that the medical students who came directly from the autopsy dissection room carried infective material with them, and a few years later he instituted a policy at the maternity division which required hand washing with chlorinated limewater. Within one month the mortality rate from puerperal fever fell to about three percent. After publishing many shorter accounts of his findings, he finally published his complete discussion in Die Aetiologie. Der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers in 1861. Semmelweis discovery of the etiology and prevention of childbed fever was truly revolutionary, saving lives and preventing suffering of women in childbirth.

The Hagströmer Library collection holds the following works by Semmelweis:

Die Aetiologie. Der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers, 1861.

Zwei offene Briefe an Dr. J. Spaeth, Professor der Geburtshilfe an der k.k. Josefs-Akademie in Wien, und an Hofrath Dr. F. W. Scanzoni, Professor der Geburtshilfe zu Würzburg, 1861.

Zwei offene Briefe an Hofrath Dr. Eduard Casp. Jac. v. Siebold, Professor der Geburtshilfe zu Göttingen, und an Hofrath Dr. F. W. Scanzoni, Professor der Geburtshilfe zu Würzburg, 1861.

Offener Brief an sämmtliche Professoren der Geburtshilfe, 1862.

Anna Lantz, 12 March 2020

Konsert på Hagströmerbiblioteket

Att mitt bland de gamla bokrariteterna i Hagströmerbibliotekets prunksal få se och lyssna till de unga musikerna i LILLA AKADEMIEN så virtuost traktera sina olika instrument blev en bejublad konsert bland höstens evenemang, som vi nu gärna vill få fler att uppleva genom ett nytt framträdande.

LILLA AKADEMIEN är en specialiserad och omsorgsfullt utformad musikskola, som grundades 1998 av den pedagogiska visionären och musikern Nina Balabina, vars konstnärliga ledare hon varit sedan starten. Idag är Lilla Akademien en väletablerad musikskola med omkring 730 barn och elever på de olika utbildningarna, i åldern 4-25 år. På några få år har Lilla Akademien vuxit till att bli en av de mest betydelsefulla och inflytelserika musikinstitutionerna i Skandinavien för utbildning av unga musiker, där en gedigen musikutbildning av hög kvalitet integreras med akademisk utbildning.

VARMT VÄLKOMNA!

ONSDAGEN 19 FEBRUARI KL. 18.00

Hagströmerbiblioteket Haga Tingshus

Buss 515 (Odenplan) Hållplats Haga Södra

Anmälan emotses före 14 februari

Email: anna.lantz@ki.se Telefon: 070 555 27 36

Förfriskningar serveras

Medlemmar inträde 130 kr Icke medlemmar 180 kr

JACOB BERZELIUS

Ingen vet mer om Jacob Berzelius och hans samtid än Jan Trofast. Hans senaste bok, Jakob Berzelius, Klarhet och sanning. Männis- kan bakom de vetenskapliga framgångarna (2018) är på 650 sidor. Men Trofast hittar hela tiden nytt material och arbetar just nu på ytterligare en bok i 400-sidors-klassen om Berzelius, en av sin tids främsta kemister. Jan Trofast kommer att väva samman den fram- stående kemistens vetenskapliga verksamhet med hans liv och umgänge. Genom den stora samlingen bevarade brev och reseanteck- ningar – både personliga och vetenskapliga – får vi följa Berzelius från barndomsåren och lära känna honom som människa. Fram träder inte bara en eldsjäl i det vetenskapliga arbetet utan också en kulturkritiker och engagerad medmänniska.

Jan Trofast är teknologie doktor i organisk kemi, vetenskaplig rådgivare inom life science, och kemihistoriker med inriktning på Jacob Berzelius och hans samtid.

MÅNDAGEN 10 FEBRUARI KL. 18.00

Hagströmerbiblioteket Haga Tingshus

Buss 515 (Odenplan) Hållplats Haga Södra

Anmälan emotses före 6 februari

Email: anna.lantz@ki.se Telefon: 070 555 27 36

Förfriskningar serveras

Medlemmar inträde 130 kr Icke medlemmar 180 kr

Spring 2020!

We are back!

Look out for the coming announcement of exciting activities at the Hagströmer Library this spring.

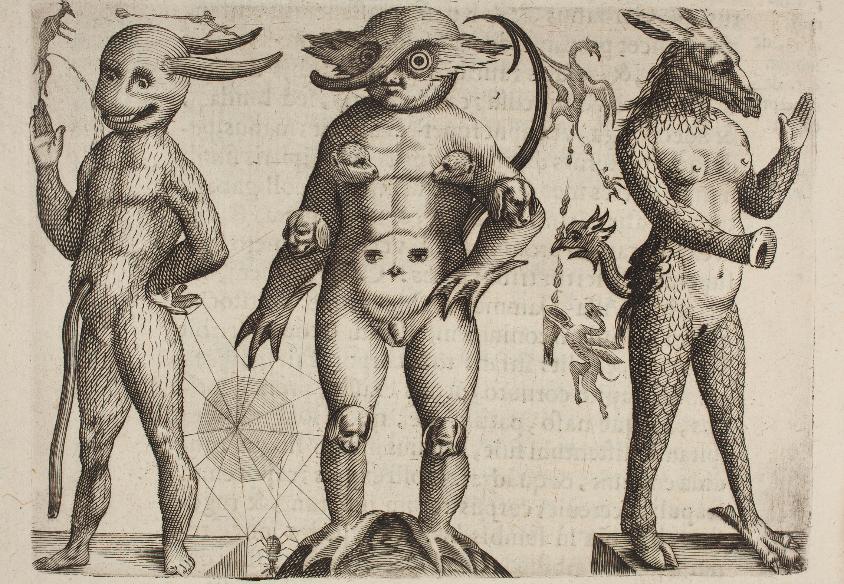

(F. Liceti, De monstrorum natura, caussis, et differentiis, Patavii, 1634)

God Jul och Gott Nytt År!

Season´s Greetings and Best Wishes for the New Year!

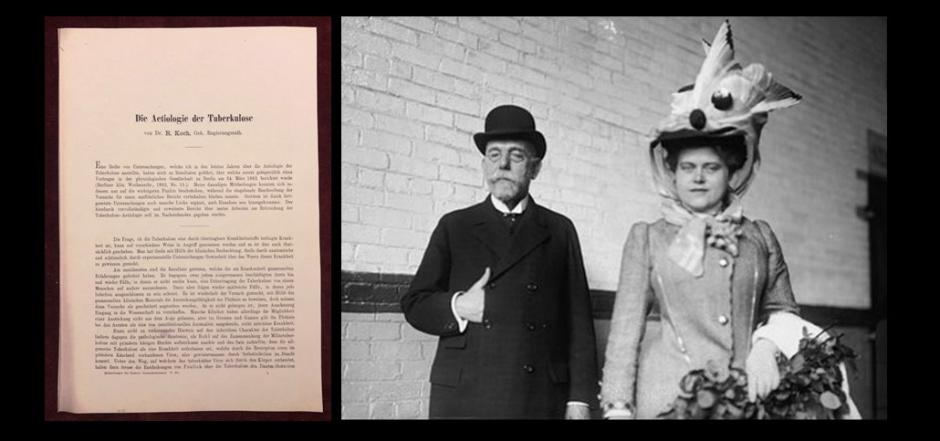

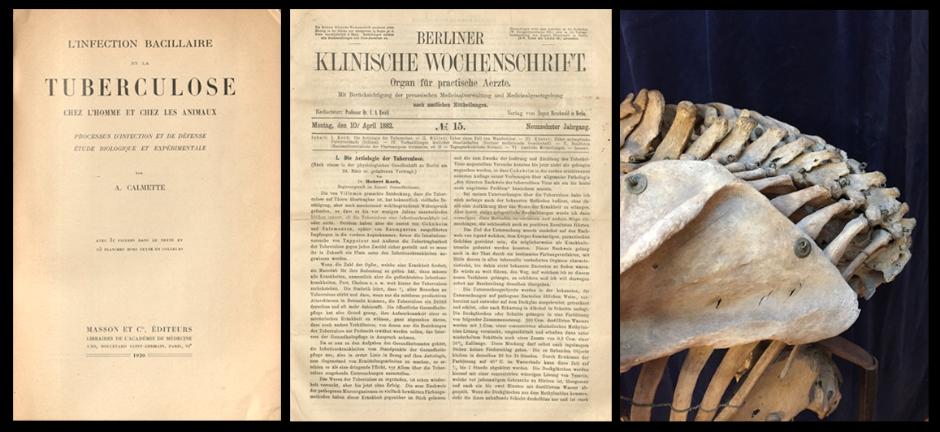

Robert Koch - 1905!

In 1905 Robert Koch was awarded The Nobel Prize in

Physiology or Medicine "for his investigations and discoveries in relation

to tuberculosis." His discovery of the tubercle bacillus was announced

1882 in Berliner klinische Wochenschrift. Two years later in 1884 he published a

fuller account in a paper Die Aetiologie der Tuberkulose in Mittheilungen

aus dem kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte 2, where he reported how he succeeded

in producing experimental tuberculosis in animals after cultivating the

bacillus.

Hagströmer Library Collection.

Anna Lantz, 11 October 2019

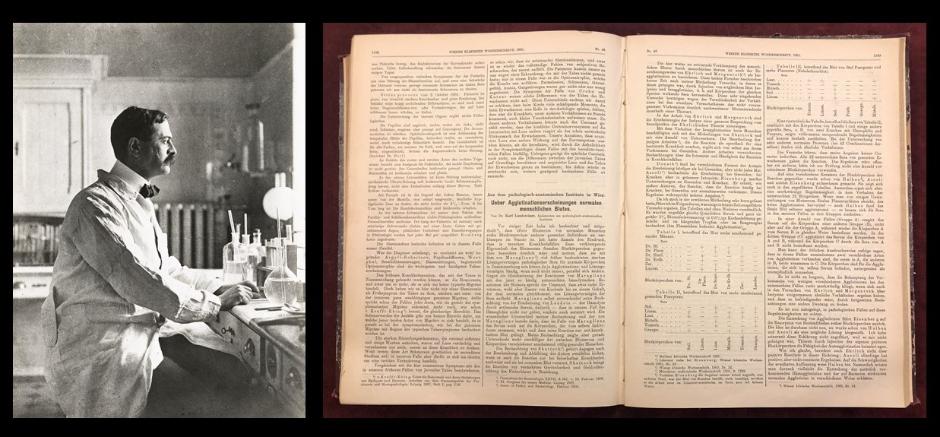

Karl Landsteiner – 1930

Landsteiner was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1930 “for his discovery of human blood groups”, which was published in a paper Ueber Agglutinationserscheinungen normalen menschlichen Blutes in Wiener klinische Wochenschrift 14, Jahrgang 1901. Hagströmer Library Collection.

Anna Lantz, 10 October 2019

Camillo Golgi!

Camillo Golgi shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Ramon y Cajal in

1906 “in recognition of his work on the structure of the nervous system”. This

work by Golgi “Sulla fina anatomia degli organi centrali del sistema nervoso”

is an extraordinary association copy as the front flyleaf has an inscription from Golgi himself to Gustaf Retzius “Herrn

Professor Dr. Gustaf Retzius Hochachtungsvoll C. Golgi”. It has 24 folding

chromolithographed plates and was printed in Reggio-Emilia in 1885. Hagströmer Library Collection.

Anna Lantz, 9 October 2019

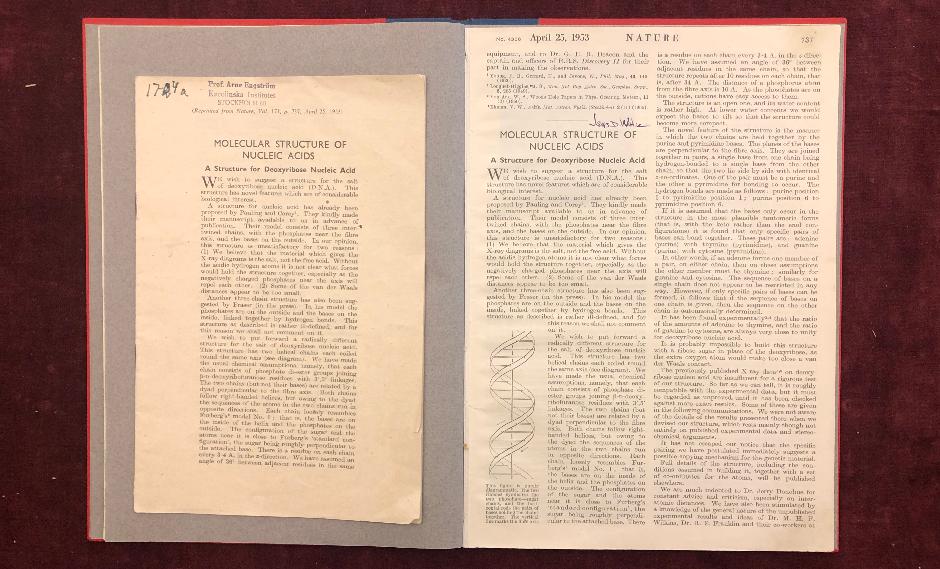

DNA - Watson, Crick, and Wilkins!

In 1962 Watson, Crick, and Wilkins were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in

Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure

of the nucleid acids". Their paper regarding the identification of the

double helix structure of DNA, and the copying mechanism of genetic material

was published in "Nature" 1953. The Hagströmer Library has both

the rare offprint of their article, previously owned by Professor Arne

Engström who held the speech when they received the

Nobel Prize, and an extract of the paper from "Nature" which Ove

Hagelin asked Watson to sign when they met in 2001 when all still alive Nobel

Prize winners in Medicine were invited to Karolinska Institutet at the

100-year-anniversary of the Nobel Prize.

Anna Lantz, 8 October 2019

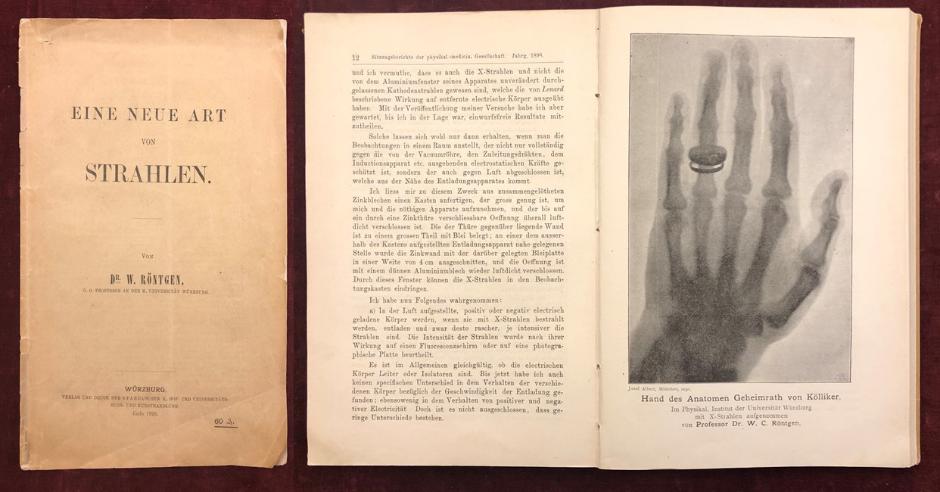

The 1st Nobel Prize in Physics!

In 1901 Wilhelm Roentgen was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the X-rays. The Hagströmer Library has both the first edition of the offprint of his "Eine Neue Art von Strahlen" printed in 1895 (Image 1), and the first edition of the two papers "Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen" and "Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen II" published in the journal "Sitzungs-berichte der Würtzburger physikalisch-medicinischen Gesellschaft zu Würzburg", from 1895-96 (Image 2).

Anna Lantz, 7 October 2019

Global Health in the Anthropocene? History and Planetary Health

Almost a year since delivering the 2018 Hagströmer Lecture at the Karolinska Institutet, it seems timely to reflect briefly on why I chose the topic of planetary health, and to touch on some subsequent developments.