The quest for eternal life

Mummies

These days, we do our utmost to prolong life, even that of seriously ill patients. There are accounts of people who, using the latest high-tech means, have had their bodies (or that of their loved ones) frozen in anticipation of new cures or methods of revivification. Certain people, such as Lenin, have been immortalised through embalming. Throughout the ages, humans have made sure to remember and cherish their dearly departed, and there is much poignant evidence of the love and consideration that endures long after death. In the Pharaoh Tutankhamen’s tomb was a lock of his grandmother’s hair and many a sarcophagus and engraved memorial stone from ancient Rome bears witness in words and pictures to the grief felt after the death of a child.

Mummification was a central pillar of ancient Egyptian funerary practice, and the pharaohs would plan their tombs from an early age, aware of the time it took to construct them and collect all the artefacts needed for the afterlife. It was believed that the soul comprised two parts, the Ka – the vital force – and the Ba – the spirit. The proper preservation of a dead body guaranteed its reunification with both parts of the soul and thus eternal life. They had separate rooms for all their accompanying possessions, including tiny figurines called ushabti to act as servants. The wall paintings inside the tombs usually come from the Book of the Dead and depict how the journey to the afterlife was to be properly navigated

While the Egyptians were experts at mummification, mummies can be found all over the world, from China to South America. The Egyptians improved the embalming technique during the New Kingdom, particularly the 18th Dynasty, which produced our best-preserved specimens. The value of the funerary objects also increased with time, and with it the number of robberies.

Sometimes the chance nature of a body’s location – be it a bog or an arid or extremely cold environment – has proved extremely preservative. Most people would have heard about Ötzi the “Ice Man” who was found in the Alps between Italy and Austria. Bogs preserve the organic material (such as hair and skin) better than the bones. It was once thought that this was solely due to the low pH, anaerobic conditions, but it was then discovered that sphagnum (peat moss) contributes to favourable chemical processes in a natural form of tanning. One bog body, referred to as the Lindow Man, is held by the British Museum, but most are found in Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands. Frequent finds were made when draining peat bogs or during times of need when peat was used as a fuel.

Egyptomania and the infancy of Egyptology

From the late 1700s until the first decades of the 1900s, a wave of Egyptomania swept through Europe. Napoleon’s Egypt campaign in 1798 catalogued the country’s monuments, fauna and flora, the scientific results of the expedition being published in Description de l’Égypte from 1809. Giovanni Belzoni (1778-1823) opened his exhibition of ancient Egyptian treasures in “The Egyptian Hall” in London in 1821, and the Rosetta Stone found by Napoleon’s soldiers in 1799 was the key that Jean-Francois Champollion (1719-1832) needed to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs in 1822. The first person to interpret the Rosetta Stone, however, was Swedish linguist Johan David Åkerblad (1763-1819), who despite his correct interpretation of some of the symbols on the stone years before Champollion, fell into oblivion. Other expeditions were then launched to Egypt and more and more mummies were discovered as royal tombs, temples and pyramids were excavated. Vast quantities of Egyptian objects were purloined, with mummies some of the most prized. People were convinced that mummy powder had medicinal properties when ingested, which was probably a case of linguistic confusion with the Persian word mumia (bitumen), a substance with antiseptic properties that was once thought to have been an essential ingredient of the mummification process. Mummies were also used to fuel steam trains, so versatile were their properties considered to be. In England, enthusiasts would host “unwrapping-parties” at which guests would gather around a mummy and ceremoniously remove its bindings and, if they were lucky, return home with an amulet discovered within. As the demand for Egyptian goods increased, many businessmen realised the lucrative advantages of this type of trade and many a shady deal was done. Unscrupulous people made forgeries and composites of objects and mummies in order to claim a higher price for a complete specimen. In more recent times, X-ray analysis has revealed that many mummies contain nothing like what was previously thought.

Of course, more serious examinations were also conducted. In 1908 Margaret Murray (1863-1963) of Manchester University carried out a scientific examination of a 12th dynasty mummy found by archaeologist Sir William Flinders Petrie (1853-1942). Petrie was a pioneer of systematic Egyptology, and was one of the foremost figures in the field along with Frenchmen Auguste Mariette (1821-1881) and Gaston Maspero (1846-1916) and Germans Heinrich Brugsch (1827-1894) and Adolf Erman (1854-1937), who all made important findings and composed lexicons. A seminal inventory of ancient artefacts was made in 1842-45 by the German Richard Lepsius (1810-1884), after which interest in mummies culminated with the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb by Howard Carter (1874-1939) in 1922, the progress of which was closely followed by the world’s press. In 1926 an early scientific examination was conducted by two French journalists using a little portable X-ray apparatus.

The Medical History and Heritage Unit manages a collection of mummified heads and bodies held in storage at the Gustavianum Museum in Uppsala. It forms part of the ongoing project to sort out Karolinska Institutet’s anatomical collections and includes a child mummy donated to Karolinska Institutet by Baron Jakob Vilhelm Sprengtporten (1794-1875) in 1850. A document in the faculty archives reads as follows: “A mummy donated by Baron Sprengtporten. [. . .] §.7 Hr. A. Retzius announced that a gift has been made to the Museum by Baron Sprengtporten of an Egyptian mummy in its coffin, wherefore the Professors have asked Hr Retzius to offer Baron Sprengtporten their sincere thanks.”

This mummy is not on display, but if on reading this you feel the need to make the closer acquaintance of other mummies, I can recommend a visit to the Gustavianum or the Egyptian rooms of the Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities in Stockholm.

Ann Gustavsson, 15 June 2017

Illustrations:

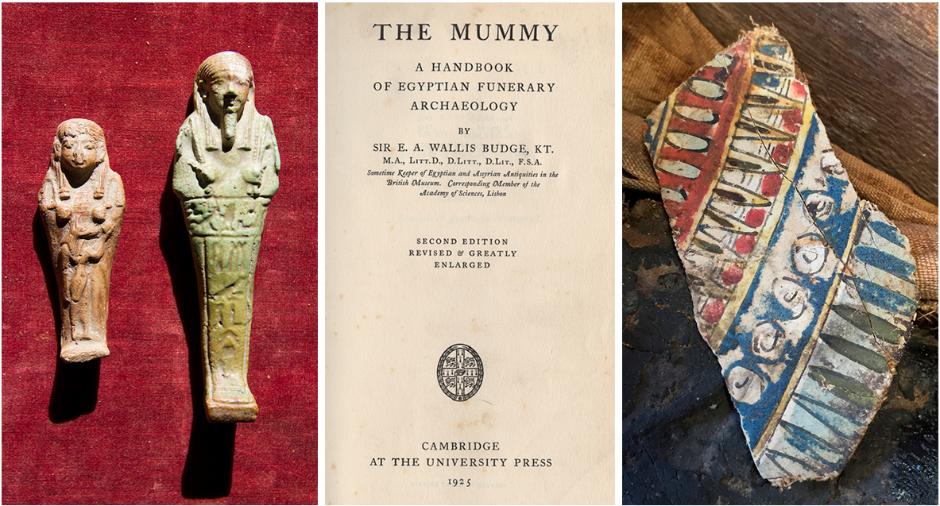

Title page from The mummy. A handbook of Egyptian funerary archaeology by Sir. E. A. Wallis Budge, 1925. Hagströmer Library.

Child mummy’s cartonnage. KI:s anatomical collection.

Ushabtis. Dan Jibreus´ private collection.

Photo: Ann Gustavsson, Dan Jibreus.

References:

Auderheide, A.C. The scientific study of mummies. Cambridge, 2003, p. 171, 175, 515ff.

Dunand, F & Lichtenberg, R. Mummies – A journey trough Eternity. London, 1994, p. 14f, 20, 23, 31, 74, 80, 98f, 112.

Lefkowitz, M.R. & Fant, M.B. Women´s life in Greece & Rome. London, 1992, p. 207.

Minten, E. Roman attitudes towards children and childhood. Private funerary evidence c.50 BC. - c. 50 – c. AD 300. Stockholm, 2002, p. 182ff.

Pringle, H. Mumiekongressen – Vetenskap, besatthet och den eviga döden. Stockholm, 2001, p. 83ff, 139, 156, 195ff.

Shaw, I. The Oxford history of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, 2000, p. 170, 303.

Document from the faculty archives, 25 March 1850, item 7, p. 57.

Learn more:

Tutankhamen and his family

14-year old girl cryogenically frozen

Piccadilly´s Egyptian Hall

Ann Gustavsson is an archivist/curator at Karolinska Institutet’s Medical History and Heritage Unit. She has a master’s degree in archaeology and another in osteoarcheology. With a background in cultural studies, she went on to read ancient history and archival science. Her speciality is pathological lesions in bone. Ms Gustavsson is currently inventorying, analysing and digitalising Karolinska Institutet’s anatomical skull collection.