A Linnaean Kaleidoscope

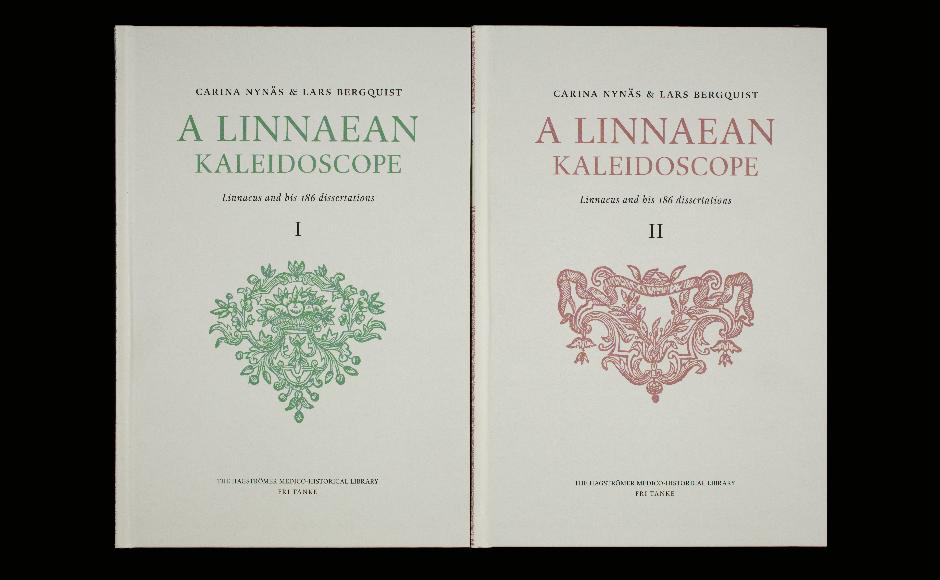

The Swedish 18th century scientist Carl von Linné (sometimes Carolus or Carl Linnaeus) has had an immense influence on the way we understand the natural world we live in. In two installments of the Hagströmer Library blog Linné will be treated starting today. A Linnaean Kaleidoscope I-II, now published as number 21 in the Hagströmerbibliotekets skriftserie, is introduced by its two authors Carina Nynäs and Lars Bergquist. Next week Ove Hagelin, who also has been instrumental in the creation of this work, will present an essay called The Hagströmer Library Series of Publications and Important Linnaeana, which details earlier publications in the series concerned with Linné. (Dan Jibréus).

The Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) profoundly and forever changed the way we think of nature and science.

Carl Linnaeus was captivated by the creed of life in God’s creation, where he himself, Linnaeus, persistently unearthed and arranged the divine order, putting the hidden system, previously wrapped up in inscrutable mystery, in a completely new context. He was able to see an eternity in each plant and to search for the significance of small shivering, shimmering insects and humble, living beings.

A Linnaean Kaleidoscope I-II, the first expanded introduction in English of all the 186 Linnaean dissertations, is not written only to bring forth the botanical, medical, zoological, geological, mineralogical and other contents important to him. As historians and biographers, theologians and philosophers of religion, we have also intended to reflect both Linnaeus and his theses in their cultural context, as well as the history of ideas and natural sciences, highlighting also the reverberations emanating from the Linnaean scientific workshop.

In theory, dissertations should be written by the students. Some did write their texts, but content and language had, as professor Bo Lindberg states, to be controlled by their professors, and in the 18th century that control was rationalized to the extent that the professors more or less wrote the dissertations themselves, for some remuneration.

The 186 dissertations, practically formulated by Linnaeus and defended under his presidency, usually present new knowledge, claiming to contribute to the advancement of natural history and medicine. Furthermore they have an international touch, reporting findings from exotic parts of the world, and sometimes being defended by disciples from other European countries.

A Linnaean Kaleidoscope, includes all 186 dissertations, reflecting imported theses as well as Linnaeus’ own domain of interest. The dissertations, written in Latin, have been available since the end of the 18th century in brief English summaries, translated by Richard Pulteney in A General View of Linnaeus’ Writings (1789, 1805).

In 1939, Gustaf Drake af Hagelsrum published a brief Swedish survey of the Linnaean theses: Linnés disputationer. Approximately half of the dissertations have been translated into Swedish as part of an ongoing project, initiated about one hundred years ago and edited by Svenska Linnésällskapet. From 1921 up to the present, 84 dissertations have been translated into Swedish in the Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift.

Thus, for over two hundred years the necessity of an updated and enlarged volume in English has become increasingly obvious. We have for almost ten years been working with A Linnaean Kaleidoscope to fill that gap.

Our work is intended for readers interested in the history of science, popular history, the world of ideas of the 18th century, and, of course, Carl Linnaeus’ personality, his way of thinking and intellectual development. As both of us have formerly been engaged in biographical studies, we regard our finished work also partly as a kind of scientific biography.

In the form of short essays we have wanted to open doors to the diverse and thrilling scientific world of the 18th century. Bones of contention in the world of the learned have therefore particularly captured our interest – as well as today less discussed Linnaean themes, such as his focus on dietetics, women’s and children’s health and pharmaceutical issues. The form we have chosen, the essay, generously allows space for the immense indigenous literature concerning Linnaeus and his scientific themes.

We have focused on the incredibly rich literature regarding Linnaeus’ world of ideas, as well as interpretations and comments on the different dissertations, instead of translating the Linnaean dissertations verbatim. Thanks to the Swedish researchers and their meticulous efforts we have obtained an immense source material, enabling us to approach Linnaeus and his dissertations from important angles.

Our ambition has also been to enlighten general questions, connections and contexts, typical of the period, and to understand Linnaeus’ dissertations in relation to both previous scientific results and sometimes even later development.

With our book we have strived to find our place between Richard Pulteney’s brief overviews and a hopefully forthcoming modern complete translation with scientific comments, made by experts from the different scientific fields.

Also Linnaeus’ relation to God and the relation between modern science and the belief in God as Creator are treated in A Linnaean Kaleidoscope. Within the frames of modern and postmodern theology Linnaeus’ physico-theological approach seems to have become extinct. The images of God and nature are also more elusive and complex than the adherents of Enlightenment believed. But the rapturous wonder Linnaeus brought about in his botanical and zoological perspectives, his impetus and zeal, his unconditional admiration and love for nature are not yet outdated.

The Linnaean Kaleidoscope I-II is beautifully illustrated with original plates and frontispieces.

Carina Nynäs & Lars Bergquist, 24 August 2016