Gigantism part 2

The Irish Giant.

The Tall Lapp Girl Kristina Katarina Larsdotter, who featured in an earlier blog, is not the only known case of gigantism. Charles Byrne was born in 1761 in the Irish village of Littlebridge, Co. Derry. He was of normal size at birth, but soon began to grow at an astonishing rate and to an astonishing size. As was the case with the Tall Lapp Girl, an explanation was sought. It was said that he had been conceived in a hayloft – hence his height. As a child he would dribble and spit copiously, which made his friends keep their distance. It has been suggested that he might have had a slight mental retardation. He suffered serious growing pains. Byrne was discovered, just like Stor-Stina, by a manager, Joe Vance, who saw in him a lucrative source of income. At first, public interest exceeded expectations, and they travelled through Scotland and Northern England on their way to London. By the time they arrived in the capital in 1782, Byrne was a celebrity and posters advertising his exhibition were everywhere. He was also the subject of much gossip and was introduced to the royal family and other aristocratic personages. It was said that he was so tall that he could light his pipe straight from the street lanterns. His income was such that he was able to buy a fine apartment, where he would receive visitors.

Gradually, however, the market for this type of spectacle became saturated, as more “giants”, we well as dwarves, were exhibited at other places, forcing Byrne to drop his price. He developed serious drink problems and was robbed of a banker’s draft that he had bought with all his savings. He also probably suffered from tuberculosis, which exacerbated his failing health.

Doctor and surgeon John Hunter was working in London at this time. He operated on patients and collected different anatomical samples and bodies both human and non-human. He was feared, since people knew that if his operations failed and the patients died, they could end up in one of his cabinets. He was particularly interested in animals and humans with morbid lesions and distinctive features, so he was naturally drawn to Byrne, especially when it turned out he was dying.

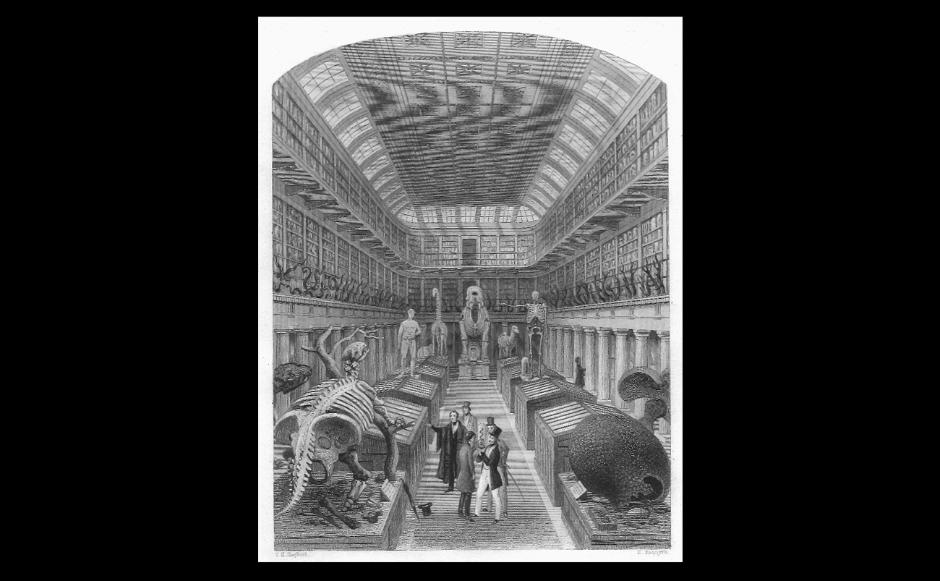

Byrne had other ideas than the Tall Lapp Girl concerning his body after death, and under no circumstances wished to end up as part of Hunter’s collection. So he paid one of his friends to make sure he was buried in a lead coffin and dumped in the sea. But this was not to be. Byrne passed away in 1783, a year after his arrival in England, at the age of only 22 and a height of 2.31 m (7 feet 7 inches). However, there was a great deal speculation about what had become of the body, as few people believed that it had been in the coffin. Either it had been removed by caretakers bribed by Hunter, who had had an accomplice stationed on the same street as Byrne’s apartment to inform him as soon as Byrne died, or simply stolen and the coffin filled with rocks before being lowered beneath the waves. Hunter then cleaned the skeleton, adding it to his collection four years later when interest in the circumstances surrounding the Irish Giant’s death had waned. Byrne’s skeleton can still be seen in the Hunterian Museum (founded in 1813), where it is one of the main attractions, despite the debate over whether it ought to be buried in accordance with his final wishes. The directors of the museum and others believe that is should be preserved for science. Already in 1909, US surgeon Harvey Cushing was able to announce by cutting open the cranium that Byrne had had a pituitary adenoma. In 2006, tissue was extracted for a DNA test from Byrne’s molars, from which scientists discovered the rare AIP mutation, leading them to draw conclusions about its heredity. Apart from the successful research that has already been done and that can help contemporary relatives and coming generations, scientists want to be able to continue using his remains for research. Another suggestion is for a replica to be made of his skeleton for exhibiting in the museum. This illustrates the predicament in which many museums now find themselves: should they preserve the remains that are possibly their greatest public attractions or return them for burial? There are countless mummies and other kinds of human remains at different museums and institutions, and such ethical issues ought to be balanced against the knowledge that can be gleaned from the research conducted on them. DNA techniques are becoming more and more refined, and it has become easier to examine trace elements, isotopes etc. in the laboratory. Nowadays, such analyses of bone samples can radically change current ideas of kinship, disease, diet, habitat and so on. The remains of indigenous peoples are often removed from institutions to be repatriated, and this applies as much to Karolinska Institutet as anywhere else; in the case of Charles Byrne, however, there is a medical aspect to take into consideration that is of much value for people living with gigantism today.

What causes such growth?

The pituitary gland, or hypophysis, secretes a number of different hormones. While it was discovered in antiquity, its function was long a mystery. Greek physician Galen (c. 129-199 A.D.) thought its purpose was to supply the nose with mucous (!). A pituitary tumour is the most common cause of gigantism/acromegaly. Descriptions of exceptionally tall people can be found far back in human history, but it was not until the second half of the 19th century that the disease was linked to pituitary tumours. In 1886, French neurologist Pierre Marie (1853-1940) described a disease involving the abnormal growth of the bones of the face, hands and feet. Acromegaly, as it is called, derives from the Greek akros (extremity) and megalos (large), and unlike gigantism only affects adults between the ages of 30 and 50, who, since already fully grown, are generally only affected in the extremities and the face. Nowadays, a combination of drugs, surgery and radiotherapy is available for patients with such tumours, and there are ways to contain the size of the tumours along with the hormone secretion that causes the abnormal growth, making it possible to slightly reduce the size of the extremities. There are also cases in which one or more of a patient’s ancestors had the same condition.

As puberty is also delayed by several years for people with gigantism, they have time to grow even more than normally growing individuals. When scientists examined Byrne’s skeleton they found that the epiphyses had not yet fused, which means that he was still not fully grown at the time of his death at 22 years old. Only about 30% of people with the AIP mutation develop a tumour, and only about 5% have a tumour that produces symptoms. The tumour, which is benign, grows very slowly and almost never spreads to other parts of the body. The symptoms can be very distressing, and include a bulging forehead, abnormally large jaw, hand and feet, and chronic headaches and perspiration. They can also suffer from disorders of the menstrual cycle and libido, while the pressure exerted by the tumour against the optic nerve can also cause visual disorders. The strangest symptom is that some men can start to produce breast milk, since the tumour secretes an activating hormone: prolactin. The disease is especially common amongst several families living in Northern Ireland. Scientists have discovered that the gene mutation sits on the 11th chromosome and traced it back to a common ancestor some 1,500 years, or approximately 66 generations, ago. If left untreated, gigantism or acromegaly can lead to an increase in mortality of 30% or so owing to problems that arise with the circulatory system and heart, and most of those who do not receive treatment die at a very young age. Scientists are still probing the diseases, researching, for instance, different functions between cells and proteins in order to learn how this mutation arises. If doctors know in advance who has this mutation, they will be able to X-ray their patients and operate before the tumour grows too large. This would not only avoid much unnecessary physical and mental pain but also make treatment much easier.

Ann Gustavsson, 17 August 2016

Learn more:

Watch BBC Documentary about Charles Byrne

Read about the Hunterian Museum

Illustration from:

Hunterian museum, Woodcut engraving, Sheperd and Radclyffe 1853. From Dr. Nuno Carvalho de Sousa Private Collections – Lisbon. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1853_-_Hunterian_Museum.jpg?uselang=sv (accessed 2016-08-15).

References:

Harvinder, S et al. "AIP mutation in pituitary adenomas in the 18th century and today". The New England Journal of Medicine, 2011, Vol. 364 (1):43-50.

Alberti, S. "The organic museum. The Hunterian and other collections at the Royal College of Surgeons of England". Medical museums – past, present, future. London, 2013, 19.

Collata, G. "In a giants´s story, a new chapter writ by His DNA". The New York Times, January 5, 2011.

Dalrymple, T. "Why the Irish giant´s skeleton remains a bone of contention". The Telepraph, December 22, 2011.

Mantel, H. The giant O´Brien. New York, 1998.

Moore, W. The knife man. London, 2006, 397ff.

"Royal College of Surgeons rejects call to bury skeleton of” Irish giant”. The Guardian, December 22, 2011.

Uddenberg, N. Lidande & läkedom II. Medicinens historia från 1800 till 1950. Stockholm, 2015, 109.

Åberg, H. m.fl. Bonniers Läkarbok; hormonsjukdomar. Stockholm, 2000, 151f.

Transcription of the lecture “A tall story: unravelling the genetics behind Charles Byrne – ‘the Irish giant’” by Professor Márta Korbonits and Brendan Holland at the Hunterian Museum November 23, 2011.