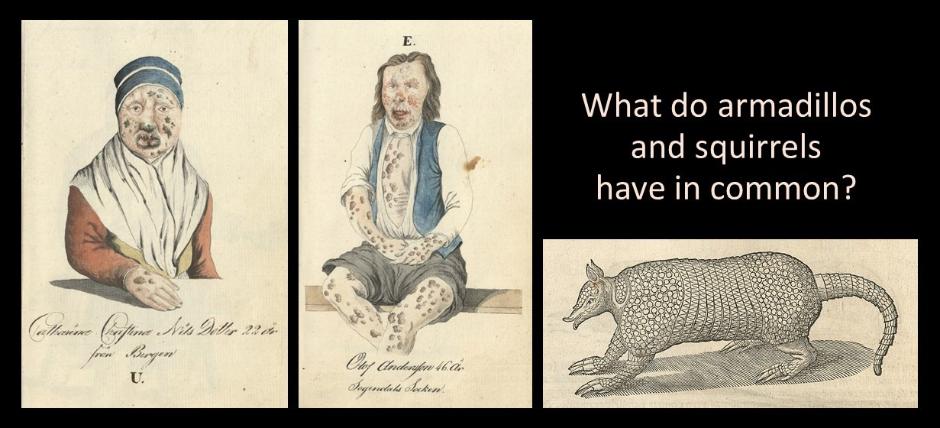

What do armadillos and squirrels have in common?

Over the past year, we have learned of the possible consequences of eating or having close contact with exotic animals like pangolins and bats. New viruses and bacteria can develop and spread at food markets when animals and meat are handled carelessly. Leprosy is a specific infectious disease that is often thought to be a thing of the past, but mycobacterium leprosa is a bacteria that still exists in many countries and that spreads through both zoonotic and anthroponitic processes (i.e. from animals to humans or vice versa). What is less well-known is that, apart from certain species of ape, armadillos and squirrels also carry the bacteria and become sick. If you want to read more about leprosy, I refer you to my blog entry of 4 May 2016.

The armadillo – certainly not man’s best friend

You could say that the leprosy bacteria has found the perfect host in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). The animal has a long lifespan, a low body temperature and lives close to human habitation. While it is not found in Europe, it is common in Central and South America. Scientists believe that humans once infected the animal and now it is returning the infection through a variety of routes. These animals are used as pets (for racing) but can also end up on barbecues due to their tasty meat after having been shot and run over. They are nocturnal and in the USA are called “Mexican road-bumps”. The infection risk has been known about since the 1970s, although it seems no one quite realised just how common it is for people to be infected. When the spread of the disease and the habitation of the animal were compared, there was a considerable geographical overlap in the graphs. Awareness has risen in recent years.

Social worker José Ramirez lives and works in Mexico and has written a book about the many years of suffering he endured after contracting leprosy, an unlikely diagnosis that was not established until the end of the 1960s – 7 years after onset. From that point on he spent many years at Carville leprosy hospital, which was effectively a leper colony. The doctors there were sceptical about his having leprosy since he had not travelled to the countries where the disease was endemic. The most likely disease vector was an armadillo. Different medicines were still being tested at this time, and powerful painkillers often had severe side-effects. One such that made it into production was the drug Thalidomide, which led to serious birth defects when taken by pregnant women. The treatment has improved over the years, but driving the bacteria from the body was once a long and arduous process, which, for the unlucky, caused severe harm before taking effect. This is still the case in many developing countries, where sufferers can sustain damage to the nerves, skin and, eventually, the bone. These days, combination preparations are used involving different types of antibiotics to achieve greater efficacy and avoid resistance. After many years of treatment José Ramirez recovered largely unscathed, since which time he has devoted his professional life to informing people about leprosy and supporting sufferers.

Professor Stewart Cole has worked at Institut Pasteur for many years and in 2007 was made professor and director of the international health and research body Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne. As some of the leading leprosy researchers of today, he and his team have used advanced DNA techniques and molecular-biological research to map the bacteria and categorise 154 strains from around the world.

The poor red squirrel

A few years ago, National Trust researchers in the UK found that the population of red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) on the British Isles have leprosy. After researching its genome, they concluded that it is a mediaeval variant of the bacteria that produces similar symptoms as those seen in humans: lumps, growths, patchy skin, etc. The squirrels lose the tufts of hair on their ears. Since squirrels were used for food (their meat is said to resemble chicken) and for their fur, there was once much more contact between us and them. Today, however, the species is protected and almost extinct, which is also a consequence of having been out-competed by the invasive North American grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). It is no longer common for squirrels to infect humans.

The beneficence of J.E.Welhaven

For his entire working life at St Jörgen’s leprosy hospital in Bergen, priest Johan Ernst Welhaven (1775 - 1828) did his best to care and make life easier for the seriously ill patients there. Apart from curing their souls, the much beloved priest collected clothes, food and medicine, which he distributed to the sick. This gave him good insight into healthcare and enabled him to get to know the patients, about whom he also made careful notes. It is not inconceivable that life-long hospitalisation awaited the incurably sick, who often lived for a fairly long time. Many of these hospitals also served as poor houses and medical institutions for the multimorbid and elderly. In the Middle Ages, Landskrona once boasted such a hospital – effectively a Swedish House of the Holy Spirit (a kind of hospital prevalent in mediaeval Europe) – but towards the end it mostly took care of other patients than those with leprosy. The Hagströmer Library holds a book containing unique hand-coloured drawings of 32 patients from the leprosy hospital in Bergen, probably drawn by Welhaven himself.

Readers interested in interdisciplinary subjects concerning veterinary versus human medicine and medical history can find out more in the anthology Humanimalt, published in 2020. This is one of a series of three books from Exempla publishers, the others being Främmande Nära and InomUtom, which are due for publication next spring and autumn respectively.

Ann Gustavsson, 15 October 2020

Illustrations:

Armadillo. From Willem Piso & Georg Marggraf & Johannes De Laet: Historia naturalis Brasiliae. Leiden & Amsterdam (1648). Hagströmer Library.

Drawings of patients. From Johan Ernst Welhaven: Beskrifning öfver de spetälske i S:t Jörgens hospital i staden Bergen i Norrige (1816). Hagströmer Library.

References:

Avanzi, Charlotte (2016) Red squirrels in the British Isles are infected with leprosy bacilli, Science 11/11.

Avanzi, Charlotte (2018) Genomics: a Swiss army knife to fight leprosy. Thèse No 8482. Lausanne: La faculté de sciences de la vie.

Gustavsson, Ann (2005 - 2006). Landskrona hospital. Leprahospital eller fattighus? Master’s dissertation in osteoarchaeology, Stockholm University.

Ramirez, José P. (2009) Squint. My Journey with Leprosy. Mississippi: The University Press of Mississippi.

Learn more: Professor Stewart Cole giving a talk, listen here!

Ann Gustavsson is an archivist/curator at Karolinska Institutet’s Medical History and Heritage Unit. She has a master’s degree in archaeology and another in osteoarcheology. With a background in cultural studies, she went on to read ancient history and archival science. Her speciality is pathological lesions in bone. Ms Gustavsson is currently inventorying, analysing and digitizing Karolinska Institutet’s anatomical skull collection.

Translation: Neil Betteridge