The Swedes in 17th Century East Asia

In the1600s,

the Dutch conquered, one by one, the trading stations and colonies of the

Portuguese maritime empire in East India. Soon, its East India Company was one

of the world’s richest, most successful enterprises. It was so big, however,

that there were not enough Dutch people to staff it: in the two centuries of

the company’s existence, it is estimated that some 300,000 German and at least

a few thousand Swedish men were in its service. One could claim, therefore,

that this was the time of the first great cultural exchange between East India

and Sweden. Yet that thousands of Swedes lived and worked in Asia during the

17th and 18th centuries is, today, a little known fact. Unfortunately, we’ll

never know anything about who most of them were, what they knew and what they

thought about their lives; but a few we do know about. Engelbert Kaempfer – a

fairly famous German traveller to Asia – knew, for example, to report that a

manager of the company’s trading station in Siam (Thailand) was a Swede by the

name of Core (Kåre?) and that he had a pet: a tame meercat, which to its

owner’s immense grief was eaten by a snake. Another, Herman Grim from Gotland,

was probably one of the most widely travelled Swedes of his age. Grim was a

company surgeon and doctor who was stationed on Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Java,

amongst other places, but who also travelled as far afield as Novaya Zamlya – in the Arctic Ocean! He

eventually returned to the Baltic, where he tried, with a modicum of success,

to capitalise on his knowledge of East Indian medicine. He spent the last years

of his life in Stockholm, where his fellow doctors considered him something of

an eccentric yet fascinating curiosity. The books he wrote while in East India,

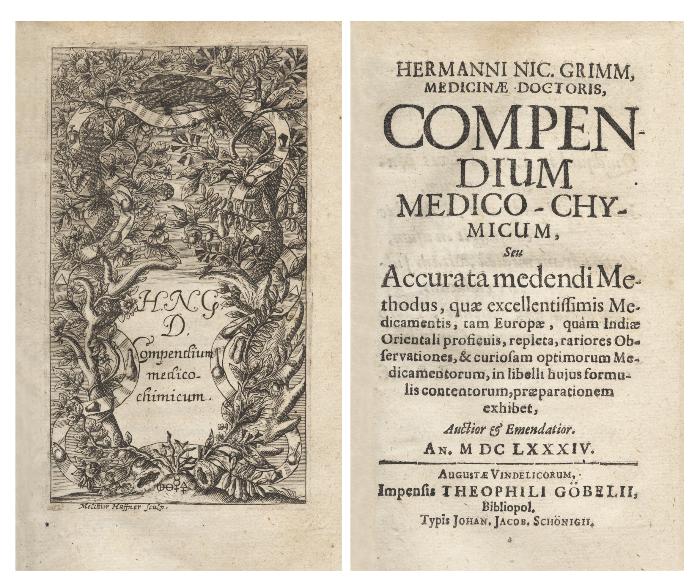

as well as many of his articles, can be found in the Hagströmer library. Frontispiece by Melchior Haffner (1660–1704) and title page of

Grimm’s Compendium Medico-Chymicum, published in Augsburg 1684.

The lecture was held at the Hagströmer library, 13 November 2014.

Text: Dr Hjalmar Fors, docent of the history of ideas and learning, Uppsala University.

Translation: Neil Betteridge.