Not everything was better before, part I

The reliance of health on an effective immune system and nutritious food is just as true today as it has always been. But this was not easy in the past, particularly for the poor. Normal folk had no access to penicillin, and until penicillin became available after the Second World War what today would be considered a mundane, easily treatable infection could prove fatal. This was a common cause of death, in fact, particularly amongst children. Penicillin was an enormous medical discovery made by Alexander Fleming in 1928, and it earned him and his colleagues Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, who helped to turn penicillin into a drug, the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1946.

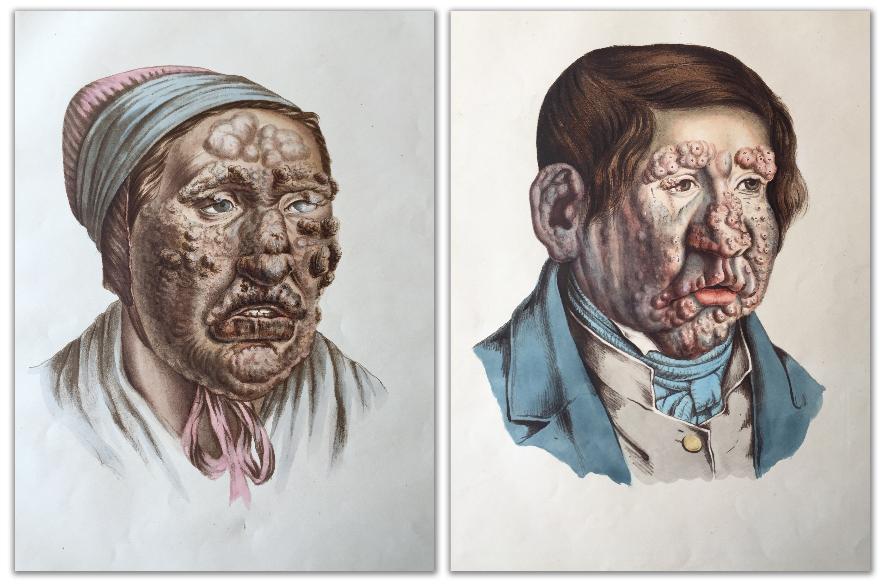

Bone material in the anatomical collection kept by the Unit for Medical History and Heritage, KI shows traces of more severe infection diseases, such as leprosy and syphilis. Chronic infection diseases can leave marks on the cranium and tibia, unlike more short-term diseases, which leave behind no skeletal evidence. The Hagströmer Library collection includes pictures of people with leprosy.

Leprosy is caused by the Mycobacterium leprae bacterium, which comes from the same family as tuberculosis, a disease that became increasingly prevalent with the decline of leprosy in the first decades of the 20th century, partly, it is thought, because people who contracted TB developed immunity to it. The leprosy bacterium was discovered by Norwegian doctor Gerhard Armauer Hansen in 1874 – hence its one-time alternative name of Hansen’s disease. In the book On leprosy and fish-eating we can find Jonathan Hutchinson’s theory that leprosy could be contracted by eating rotten fish (something to bear in mind, perhaps, when shopping for the evening meal!). This Hansen rightly believed to be completely wrong.

The incubation time can sometimes be as long as 40 years, but the speed with which the disease develops and how it manifests itself differ widely. As with many other diseases it depends on the strength of the immune system of the person contracting it. It does not seem, however, to be especially infectious, and people living in the same family as an infected individual sometimes remain healthy. Amongst other organs, leprosy hits the nerves and the skin; lumps and swellings develop, and eventually the bones themselves are affected, causing a condition called Facies leprosa in which the hard palate and nasal bone atrophy and corrode. Since the bacteria also attack the middle bones of the hands and feet, fingers and toes eventually drop off too. The loss of sensation can lead to secondary risk and injury, since it can lead to reduced mobility and impaired speech and vision. It is usually such secondary diseases, such as blood poisoning, that are the cause of death.

The oldest documented case of the disease is found in India from around 300 BCE, while tuberculosis appears to have existed in Egypt as far back as Pharaonic times. Leprosy was mentioned in the Bible, but there is some doubt as to whether it is the same disease we mean today.

In Sweden, leprosy has been around since the 1100s, and persisted for many centuries. The last patient was discharged from a hospital in Järvsö in 1943, and the last fatality was in 1976. During the Middle Ages, special leprosy hospitals were established to care for these stigmatised people, who, until then, had lived largely as social outcasts, forced to wear distinctive clothing and rattle bells and the like to warn people of their approach. Leprosy was common on Crete, which built several lepers’ hospitals and even a leper colony, Spinalonga, that was still in use by the mid-20th century. Once the island was a place where the sick and their families were deported; now it is a tourist attraction.

In the 1940s, doctors tested a preparation of sulphur, which proved effective. They subsequently prescribed a combination of antibiotics to prevent the bacteria becoming resistant. This is the same method used today for tuberculosis, which is once again on the rise. Leprosy still exists in countries like India, Brazil and Burma, but ignorance and shame force the sick into their homes and away from the hospitals. What relief you will probably feel now, the next time you catch a cold that passes in a week!

Ann Gustavsson, 4 May 2016

References:

Ehlers, E & Cahnheim, O. Die lepra auf der insel Kreta. Leipzig, 1901.

Danielssen, D.-C., Boeck, W. Traité de la spédalskhed ou éléphantiasis des Grecs. Atlas de 24 Planches coloriées. Paris, 1848.

Hutchinson, J. On leprosy and fish-eating. London, 1906, 5f.

Uddenberg, N. Lidande & läkedom I. Medicinens historia fram till 1800. Stockholm, 2015, 133ff.

Åbom, P.-E. Farsoter och epidemier – en historisk odyssé från pest till ebola. Stockholm, 2015, 26-42, 386-388.

Illustrations from Traité de la spédalskhed ou éléphantiasis des Grecs. Atlas de 24 Planches coloriées by Danielsson & Boeck. 1848.

Translation: Neil Betteridge