Berengario da Carpi in the Hagströmer Library!

One of the very rare books in the Hagströmer Library is Isagoge breves printed in 1522, known in less than ten copies in the world. Two of these are to be found in Sweden at the Hagströmer Library and at the university library in Uppsala as part of the Waller collection. It is a descriptive anatomy and a manual on how to dissect the human body illustrated with woodcuts, presenting the most comprehensive and independent understanding of human anatomy at the time. The author is Jacopo Berengario da Carpi (ca 1460- ca 1530), one of the most important Italian anatomists before Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) and Isagoge breves is one of his best known works and a great scientific achievement.

Berengario´s life

Berengario grew up in Carpi in the region of Emilia Romagna in Northern Italy where his father was a barber-surgeon. He spent his youth in the company of Alberto Pio, son of the Lord of Carpi and they had the same teacher in Aldus Manutius, the great humanist printer, who lived and taught there in the 1470s. Berengario probably never went to medical school before going to Bologna for his doctorate in the 1480s, instead he learned both anatomy and dissecting from his father and his own practical experience. In 1489 he received his degree in Bologna, and the years directly thereafter are quite unknown. Because of political events and the troubled history in the area he probably had access to plenty of dead and wounded bodies to dissect and practice anatomy on and gained medical success by his skill in surgery and practical medicine. In 1502 he became Lecturer in surgery in Bologna, a position he held until 1527 and when the plague broke out there in 1508 Berengario was also appointed what today would be called Commissioner of Health in order to fight the plague.

He had a large clientele and built himself a fortune as physician to the rich and powerful in Bologna and the surrounding areas. In 1516 he bought a palazzo where he held his art collection which included a roman torso, a painting by Raphael, works by Benvenuto Cellini, and others. Around this time Berengario was called to Florence by the pope Leo X to treat one of his friends there and he also successfully treated the pope´s nephew Lorenzo de Medici, Duke of Urbino, for an injury to the head. Later in 1526 Berengario spent some time in Rome on the request of another pope, Clement VII in order to treat people suffering from syphilis, using mercury(!). Cellini, who met him there writes: “a very shrewed person he was, too, he did wisely in leaving Rome; for not many months after, all those whom he had treated were a hundred times worse than before, and he would have been killed had he stopped”. Cellini also complains that Berengario was expensive and charged his clientele huge amounts for his service. Altogether he seems to have been quarrelsome and ferocious, sometimes threatened by severe punishment and even death, but his influential friends usually saved him. When he died in Ferrara around the year 1530 he was a wealthy man known all over Italy.

Isagoge breves of 1522

The main source for anatomical knowledge in the early 16th century were the writings of Galen who were active in the 2nd century AD, and whose works had dominated anatomical knowledge and learning ever since. His texts were used at universities all over Europe and their authority were never disputed nor contradicted. Berengario who knew them well and published several books on anatomy himself often referred to Galen in his texts, one of them being Isagoge breves. Isagoge breves is an instruction book in anatomy and dissection, a manual for students, with extremely detailed information on the anatomy of the entire human body, as he knew it. In this work Berengario is among the first to trust his own scientific inquiry and thereby putting some of the authority of Galen´s texts into question. Furthermore the illustrations were the most comprehensive attempt of making anatomical images from nature instead of the traditional schematic figures. Some even claim his anatomical figures to be the first ever made drawn from nature. He writes himself that a good anatomist “does not believe anything in his discipline simply because of the spoken or written word: what is required here is sight and touch.”. At the time he had the most independent knowledge and accurate scientific understanding of the human anatomy and Isagoge breves was an important contribution to the development of modern anatomy. Immediately after it was printed it became the most authoritative book on the subject before Andreas Vesalius´ Fabrica of 1543, a truly remarkable achievement.

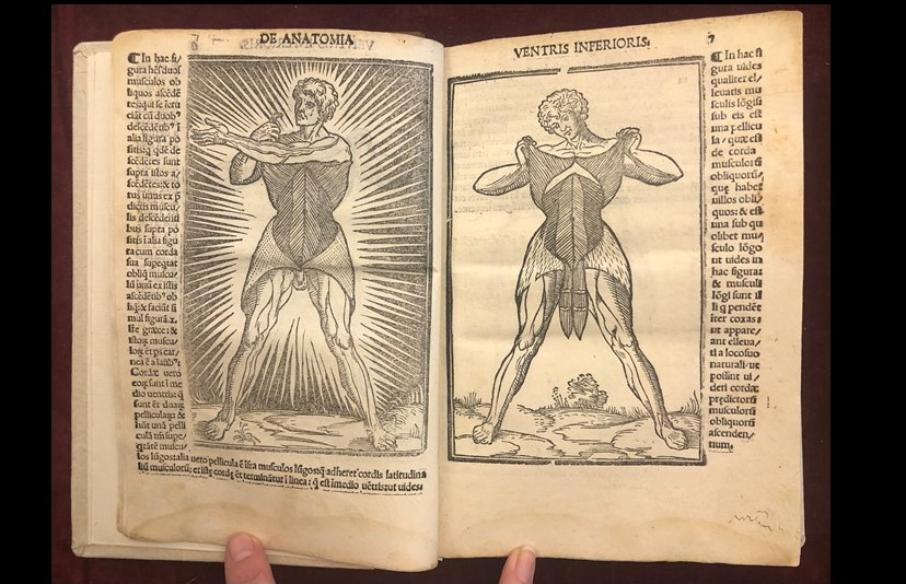

The title page has a beautiful floral border and as in many books at the time both the colophon and the printers mark are found at the very end of the book. In total there are nineteen full page and two smaller anatomical woodcuts in the book and only a few of them will be briefly discussed here. The majority of the illustrations depicts muscle manikins, all together nine images. These figures are all placed in front of a landscape background making an aesthetically bold and graphic statement. The second manikin is the most dramatic with its strong rays of light in a dark sky behind the figure. Another noticeable manikin is holding a rope in his hand, maybe indicating that ropes were often used for suspending the corpse for muscle studying, and that most of the corpses used by anatomist were from dead criminals executed by hanging.

There are two images of skeletons in the book. One is depicted seen from the front with picturesque houses and trees in the background, seemingly smiling and in movement with the arms moving from side to side. The other skeleton is depicted from the back standing in front of grave (?) surrounded with rocks and shrubberies with a town at the horizon, holding one skull in each hand as if juggling. In effect the three skulls in this image are all depicted from different angles, whereby both the top, back, and side of the skull is shown. These two skeletons with their vivid and lively appearance might be based on to the iconography of the dance of death, which was a well-known motif with a long tradition in Italian art, and in other parts of Europe as well. The other illustrations in the book depict arms, legs, and the female reproductive organs among other things. The artists name is unknown, but several names has been suggested. Regardless who the artist was, these illustrations had a great impact on later anatomical images such as the famous muscle manikins placed in beautiful landscapes in Vesalius´ Fabrica.

Isagoge breves is a small and portable book of ca 205 x 140 mm, making it easy to carry around and to use, which might be one of the reasons why there are so few copies still in existence today. The first edition of 1522 which has been discussed here was printed in Latin by Benedictus Hectori in Bologna, but several editions were printed thereafter which are also rare. For all who wish to see all the images referred to in this text please visit Friends of Hagströmer Library on Facebook (Hagströmerbibliotekets vänner), for those who wish to study the entire work page by page, the Wellcome Library has digitized their copy of the book, and for those lacking knowledge in Latin there are at least two English translations of Isagoge breves, one made in 1660 and another in 1959. Please see the links and the references below!

Anna Lantz, 23 April 2020

Links

View the images discussed in this text: here

View Isagoge breves online: here

References

Berengario da Carpi, Jacopo, Isagoge breves, perlucide ac uberime, in Anatomia[m] humani Corporis. (Bologna: Benedictus Hectoris, 30 December 1522)

Berengario da Carpi, Jacopo, A short introduction to anatomy (Isagogae breves) Jacopo Berengario da Carpi translated with an introduction and historical notes by L.R. Lind and with anatomical notes by Paul G. Roofe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959)

Carlino, Andrea, books of the body: anatomical ritual and Renaissance learning translated by John Tedeschi and Anne C. Tedeschi (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999)

Choulant, Ludvig, History and bibliography of anatomic illustration by Ludwig Choulant, translated and annotated by Mortimer Frank. Further essays by Fielding H. Garrison, Mortimer Frank [and] Edward C. Streeter, with a new historical essay by Charles Singer, and a bibliography of Mortimer Frank (New York: Schuman's, 1945)

ANNA LANTZ, MA, curator of rare books and prints at the Hagströmer Library is an art historian and book historian specialising in early modern medical illustrations and printmaking techniques.