Mycobacterium tuberculosis – the white plague

Tuberculosis is one of the specific infection diseases that has claimed – and is still claiming – many lives. It is called the white plague, a name that was very probably coined to contrast it with the Black Death, as the bubonic plague was known. And while sufferers turn very pale, the notion of whiteness can also be associated with youth and innocence. Children are more susceptible to infection than adults. After a sharp decline of the disease in Europe with the arrival of antibiotics and improvements in living standards after the Second World War, the disease is on the rise again, especially in eastern Europe. The problem of bacterial resistance means that the disease can become a serious threat again unless a new vaccine is found or antibiotic use is reduced around the world, as this merely increases the populations of resistant bacteria.

Symptoms and history

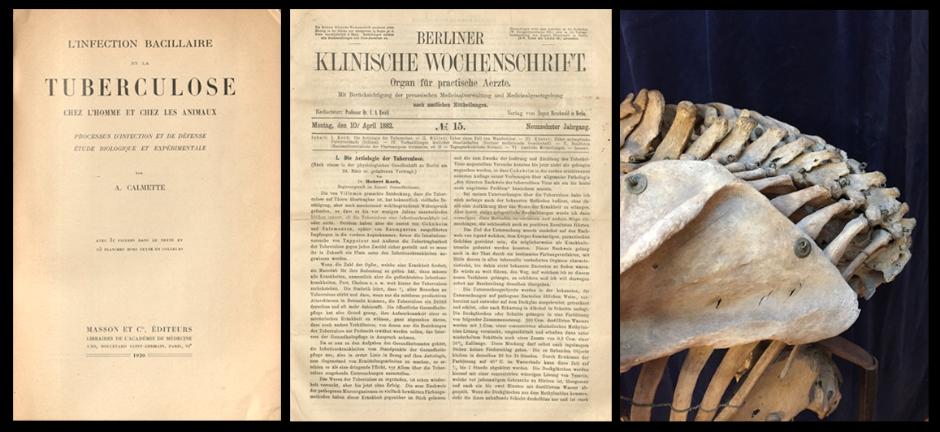

Pott’s disease, or Pott’s hump, is a pathognomonic (typical) abnormality associated with tuberculosis. When the vertebrae collapse and ankylosis (fusion) causes them to fix in place, the back takes on a sharp forward-leaning curvature – or hump. Often, the ribcage and collar bones take on a new shape to help the body cope with the deformation. We have three cases amongst the skeletons in the collection of the Medical History and Heritage Unit at Karolinska Institutet. Tuberculosis is caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacterium, which was discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch (1843-1910), earning him the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1905. While only one in ten people with the bacteria develop tuberculosis, the disease can lie dormant in the body for decades, often breaking out when the immune system is weakened. White Fox, a Pawnee native American who arrived in Sweden in 1874 to perform, died of tuberculosis, and his remains were taken into the care of KI. The skin from his torso was repatriated later, but not before it had been analysed by microbiologists at KI to ensure that it was no longer infectious. It is interesting to note that Robert Kassman, White Fox’s impressario/partner, died of the same disease (intestinal tuberculosis) 35 years later. Given the properties of the bacterium, it could very well have been the same strain that killed him. It is estimated that about one third of the world’s population carry the bacterium in a latent state. The bacterium is extremely robust and can survive for months outside the body, maybe even longer. My uncle contracted tuberculosis as a child in the 1930s from second-hand clothes and died at the age of two. No one else in the family was infected.

There is a bovine strain of the bacterium that can spread via meat and milk, otherwise it can infect via airborne transmission, just like leprosy. First, nodules (tubercles) form in the lungs – this is the infection tissue. The bacteria can remain in the lungs or can be spread. Pleural plaques (a kind of calcification of the soft tissue) can also form in the lungs. Two to seven per cent of tuberculosis patients develop skeletal tuberculosis. As well as the vertebrae, tuberculosis can affect the major joints (arthritis of the hip) and cause bone growth on the back/inside of the ribs. The symptoms of the disease depend on the organs affected, but generally include fatigue, anaemia, emaciation, diarrhoea and nocturnal fever-like sweats. The bacteria can settle in the stomach or intestines. Pulmonary tuberculosis nearly always induces coughing or even haemoptysis (the expectoration of blood). It is mostly contagious within families, with small children being particularly susceptible.

Given the tuberculous deformities found in Egyptian mummies, we know that tuberculosis has existed for at least 9,000 years. The disease arrived in Sweden in the middle ages, and in France and England it was believed that sufferers could be cured by being touched by royalty.

Treatments

It was once common for the sick to be treated with fresh air and nutritious food and to be put to bed outdoors. Many sanatoriums were built to help cure the sick and to keep them isolated. Doctors would aerate (pierce) or gas the diseased lung in an attempt to inactivate the disease and rest the organ; they also might fill the lung with oil. In Sweden, a cardiologist called Clarence Craaford developed a surgical method for removing parts of the ribs via the back, which could alleviate the disease. While excising parts of diseased lung tissue (lobes) was an option, in some more severe cases it was necessary to remove the lung altogether.

It took a long time for scientists to find an effective cure for tuberculosis, partly because the bacterium has a very resistant outer membrane and partly because the disease puts itself in a latent state and hides away in the body. Many people were infected without them or anyone else realising they were sick. Doctors started to use X-rays to see who had morbid abnormalities in the lungs, and to analyse expectorations under the microscope, which could reveal the type of mycobacterium they were dealing with. It takes a long time to cultivate the bacterium in the lab. Ventricle rinsing and bronchoscopy are other methods that have been used. If the tuberculous focus is elsewhere, doctors can analyse urine, pus, bone tissue or lymph glands. In 1921 Frenchmen Albert Calmette (1863-1933) and Camille Guérin (1872-1961) succeeded in producing a vaccine, initially one administered orally and then later by injection. Everyone born in Sweden between 1940 and 1975 was vaccinated, but even though the disease is starting to make a comeback in other countries (e.g. Russia), few people are inoculated today. A vaccine does not last a lifetime, and scientists are today working on a more effective agent. Using so-called tuberculin tests they can determine if someone has already been exposed to the tuberculosis bacterium or the vaccine. Chemotherapies (fully synthetic), such as PAS (para-aminosalicylic acid), sulfa, quinine and arsenic preparations, were the first medicines. PAS was developed by the Danish researcher Jörgen Lehmann (1898-1989), who was working at Sahlgrenska Hospital in Gothenburg, and the antibiotic streptomycin by Selman Waksman (1888-1973) and Albert Schatz (1922-1995). Waksman received the second Nobel Prize awarded for tuberculosis in 1952. These medicines, which appeared during the Second World War, are the most used and the most effective. At first, some antibiotics were powerfully allergenic and PAS tasted foul. But by this time, tuberculosis had already begun its decline, very much thanks to rising living standards. Famous sufferers in history include John Keats, the Brontë sisters, Charles Dickens and Alexandre Dumas.

The future

Better medicines have been developed over time, but one concern is that

the bacteria can develop resistance, so today patients are given four different

kinds of antibiotic at once. Treatments that once took at least two years can

now be completed in six months. If the bacteria are growing resistant, which is

becoming increasingly common with the over-use of antibiotics, treatment will

become all the more difficult.

Illustrations:

L´infection bacillaire et

la tuberculose chez l´homme et chez les animaux, A. Calmette, 1920

Die

Aetiologie der Tuberkulose. Mittheilungen

aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte. Berlin, 1884:

1.

Section of a spine with Pott’s disease.

Photos: Ann Gustavsson

References:

Bergmark, M. Från pest till polio. Stockholm, 1957: 172-177.

Jibréus, D. White Fox´ långa resa. Stockholm, 2013: 59, 79.

Roberts, C. A. & Buikstra J. E. The bioarchaeology of tuberculosis. A global view on a reemerging disease. Gainesville, 2003.

Hjärt- och lungfondens temaskrift om tuberkulos. Stockholm, 2010.

Åbom, P-E. Farsoter och epidemier. En historisk odyssé från pest till ebola. Stockholm, 2015: 44-77.

Bynym, W & H. Great

discoveries in Medicine. London, 2011: 160-162

Ann Gustavsson

is an

archivist/curator at Karolinska Institutet’s Medical

History and Heritage Unit. She has

a master’s degree in archaeology and another in osteoarcheology. With a

background in cultural studies, she went on to read ancient history and

archival science. Her speciality is pathological lesions in bone. Ms Gustavsson

is currently inventorying, analysing and digitalising Karolinska Institutet’s anatomical

skull collection.