Some spinach a day keeps the doctor away

Eating nutritious food has always been important to

good health. If we don’t get enough nutrients in our early years or if our diet

is too samey, we can develop deficiency diseases that, at worst, can leave

traces on our bones. There are several such marks that are relatively common

when making osteological analyses, some of which can be seen in the material

housed in the anatomical collection at KI’s Medical History and Heritage

Unit.

Common signs of deficiency disease

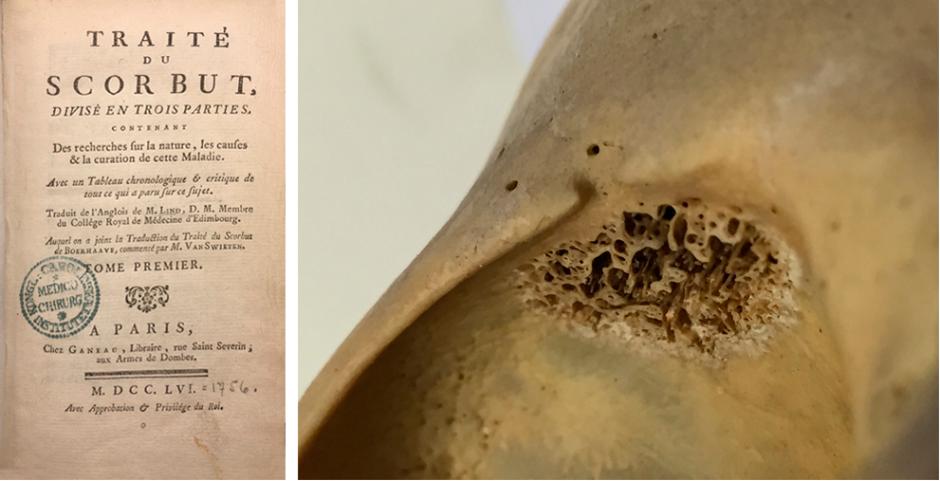

Starting with the skull, malnourishment often manifests itself as visible changes in the orbital roof,

where tiny holes and porosities form that in severe cases can suspend like peat

moss. The condition is called cribra orbitalia, and has

traditionally be interpreted as a sign of iron deficiency anaemia. Anaemia has

several different aetiologies. Low birth weight can make an individual more

precociously susceptible. Diarrhoea, haemorrhaging and intestinal parasites are

other possible causes. Similar hole patterns can also be seen on the top of the

skull, where they are called porotic hyperostosis. This kind of

skeletal change is most common in children, as it generally heals in adults.

This is because young individuals have a great deal of red bone marrow, which

more readily reacts with this type of lesion. In recent years, researchers have

looked into if it might be caused by a deficiency in something other than iron,

such as vitamin B-12. Since the most sensitive time is childhood, physiological

stress can leave traces in the form of visible, even ridged horizontal stripes

that appear mainly on the incisors. This condition is called enamel

hypoplasia and develops while the teeth are developing. It is possible

to calculate at which age the stripes appeared; if they are on the milk teeth,

it means the child suffered stress while still in the womb – i.e. that the

mother suffered stress or some kind of deficiency while pregnant. While it is

not fully known what causes the striping effect, researchers have been

interrogating the possibility that it is a result of stress related to

childbirth, malnutrition/stunted growth, imprisonment or other kinds of social

stress. Other stripes that can appear on the long tubular bones are

discoverable by X-ray and are called Harris lines.They too

can be caused by disease or trauma and appear when growth is suspended, but

whether this suspension is natural, given that growth can stop and spurt in

different periods, is a moot point.

Scurvy

These days, we know that scurvy is caused by vitamin C deficiency, and most people know that sailors

could lose their teeth when they were at sea for long periods of time with no

access to fresh fruit or vegetables. For some sailors, vitamin C deficiency

could be so severe as to prove fatal. Vitamin C, or ascorbic acid, helps to

build a strong immune system as well as cartilage and bone tissue, but cannot

be produced by the body. Scottish navy doctor James Lind (1716-1794) discovered

that the juice of citrus fruits could help the complaint and started to work on

prophylactic measures. Lind had several predecessors, but it was his work that

led to the discovery. Thanks to Lind, many hygiene and sanitation improvements

were made to life on board. He was the first person to make a thorough and

documented medical study on humans. At the Hagströmer Library, we have copies

of the first French edition of Lind’s Traité de scorbut. It was

published in 1756 and is thought to be as rare and prized as the first English

edition A treatise of the scurvy from 1753.

The critical component of vitamin C was not discovered until 1927 through the

work of the Hungarian biochemist Albert Szent-Györgyis (1893-1986), whose

research went on to earn him the Nobel Prize in 1937.

Traces of vitamin C deficiency are seldom found in archaeological bone matter

since it expresses itself in swollen mucosa, bleeding in the skin, periosteum

and gums and periodontitis, the causes of which are many. Vitamin C also helps

the body to absorb iron. This deficiency was probably more uncommon before the

introduction of agriculture when hunter-gatherers would eat more fresh and

unrefined food, such as berries, fruit and vegetables. Part of the vitamin is

destroyed during cooking and boiling. Maize, which was introduced to Europe by

Columbus, has often been associated in archaeological studies with a

deterioration in public health. It is high in sugar and starch and has been

shown to impact on both dental health and iron absorption. However, the plant

has been a food staple for centuries in other parts of the world. The conclusion

can be drawn that the advent of agriculture contributed to a slow decline in

human health. Very much on account of the increase in wheat and maize in the

diet but also of settlement, the consequence of which was the more rapid spread

of disease, with the accumulation of waste and stagnant water aggravating

bacterial growth and animal husbandry aiding the transmission of zoonoses.

Both lactose and gluten intolerance appeared after the arrival of

agriculture, although the pattern is complex and the changes gradual. For

instance, in Southeast Asia and Japan, where the staple food is rice, caries

has not increased since its introduction. It’s always hard to compare

hunter-gather societies and modern agriculture with the early agrarian

societies. Archaeologist Charlotte Roberts stresses that one must also factor

genetics and environment into understanding how the human body reacts to

different conditions.

Rachitis or the “English disease”

Once, rachitis was mainly common in children. The

condition is more commonly known as rickets and is caused by severe vitamin D

deficiency, which eventually gives rise to soft bones, a condition that in

adults is called osteomalacia. This softness is especially evident

in the long tubular bones of the arms and legs, which become bent under load.

The disease can also cause deformities in the pelvis, which can later lead to

life-threatening complications during childbirth. The KI collection houses a

couple of examples of babies who died of the disease before the age of 2,

probably from a combination of infection (maybe TB) and muscle weakness. In

Sweden, folk traditions were once rife about rickets and how it could be cured.

Protective amulets were common as a prevention, while it was thought a special

tree with a natural crevice or looped branch large enough to pull the sick

child through (known as a vårdbundet or “care-bound” tree)

possessed curative powers. A photograph of this practice (called smörjning)

can be seen in the Digital museum. Dr Nils Rosén von Rosenstein (1706-1773)

wrote a long account of childhood rickets, claiming that “the disease shows

itself when the child starts to teethe. Should it then proceed to become

emaciated, should the skin start to slacken and the belly to swell,

particularly on the right, the head to grow large, the face to become puffy and

pale with large veins in the neck, and the bone around the joints to become

enlarged: it thus already has a strong touch of this disease.” The description

continues in the same style. He also warns that “Women who have or have had

this ailment should think well before marrying. If their pelvis has become too

narrow they will either have difficult deliveries and tend to produce stillborn

babies or will die in childbirth.” According to Rosén von Rosenstein the

English disease had several causes, but usually the blame was placed on the

parents, who had brought the disease upon the child through their advanced age

or promiscuity; or on the baby having been raised in a “low-lying, damp and

marshy place”. He thought that children with rickets had too much acid in the

body. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Henrik Berg’s (1858-1936) Läkarbok was

a standard medical work. Berg recommended, amongst other things, fresh air and

sunshine, saline baths, horse-hair mattresses, dry-rubbing with wool and

washing with salted aquavit. Potatoes and farinaceous food was to be reduced in

favour of fresh milk, eggs, good quality bread, grain-based soups, meat soups,

gruel, wholemeal bread, rusks, fruit, berries and vegetables – a diet that

wasn’t always so easy for a poor family. Rickets often went hand in hand with

tuberculosis.

Rickets was, as its popular epithet implies, a common disease in English

industrial towns, where buildings were densely packed and very little light was

let in between the houses and the factories. Many English doctors looked into a

possible cause. One theory was that the muscles grew more slowly than the

bones, which thus became curved. In was only in the 1700s that doctor Thomas

Percival (1740-1804) discovered that cod liver oil was an effective

prophylactic, but it was not until the 1900s that scientists began to

understand the relationship better. In the 1930s, after further research, Nobel

laureate Adolf Windhaus (1876-1959) was able to demonstrate that the substance

ergosterol was converted into vitamin D when the skin was exposed to sunlight.

Eventually, children started to be given fish liver oil, then vitamin A/D – and

these days only vitamin D drops. In Sweden, dairy products have been fortified

with vitamin D since the 1960s. Nowadays we know much more about the body’s

vitamin D needs. Ninety per cent of essential vitamin D (which is actually a

prohormone) is produced in the skin through exposure to the sun. The primary

function of the vitamin is to regulate the amount of calcium and phosphor in

the blood to ensure effective bone mineralisation. It also helps the body to

absorb calcium from the gut. It is not that common to find curved long tubular

bones amongst osteological material or in anatomical collections, for even if a

child is affected by the disease, the bones can remould themselves and regain

their strength later in life. In today’s society, the disease is sometimes

found in people who cover themselves for religious reasons and thus deprive

their skin of sunlight. Symptoms can be a pricking sensation in the hands or

muscle cramp. Pregnant and nursing women are particularly vulnerable. A

correlation can also be seen with diets that are low in dairy products and high

in fibre. A child also risks suffering vitamin D deficiency if its mother had

low vitamin D levels during pregnancy; elderly and sick people who spend

lengthy periods of time inside either in hospital or at home without access to

the outdoors are in the risk zone. A moderate amount of sunlight is therefore

vital for everyone. Many people take vitamin D supplements during the winter,

and research continues on what the long-term effects of vitamin D deficiency

might be.

Ann Gustavsson, 22 January 2019

Illustrations:

Title page from Traité de scorbut by James Lind, 1756. From

the Hagströmer Library collections.

Close-up of the orbital roof with cribra orbitalia. KI’s anatomical

collection.

Photos: Anna Lantz and

Ann Gustavsson.

Bibliography:

Aufderheide, A.C. & Rodríguez-Martin, C.The Cambridge

encyclopedia of human paleopathology. Cambridge, 2011:

305-314.

Berg, H. Läkarebok. Nya omarbetade och tillökade upplagan. Del

3-4. Göteborg, 1919.

Brickley, M, Ives, R.The bioarchaeology of metabolic bone disease.

Oxford, 2008: 41-74, 75-150.

Larsen, C.S. Bioarcheology. Interpreting behavior from the human

skeleton. Cambridge, 1997: 29ff, 45-46.

Ortner D.J. Identification of pathological conditions in human

skeletal remains. San Diego, 2003: 383-401.

Roberts, C. & Manchester, K. The archaeology of disease.

Gloucestershire, 2010: 234ff.

Roberts, C. & Manchester, K. What did agriculture do for us? In

G. Barker & C. Goucher (Eds.), The Cambridge World History 2015: 55-92.

Rosén von Rosenstein, N. Underrättelser om Barn-Sjukdomar och deras

Bote-Medel; Tillförene styckewis utgifne uti de små Almanachorna, nu samlade

och förbättrade. Stockholm, 1764.

(Nyutgåva: Jägervall M. Nils

Rosén von Rosenstein och hans lärobok i pediatrik. Lund,

1990.)

Uddenberg, N. Lidande & läkedom I. Medicinens historia fram

till 1800. Stockholm, 2015: 13, 261, 285, 291,325, 327f.

Uddenberg, N. Lidande & läkedom II. Medicinens historia från

1800 till 1950. Stockholm, 2015: 148, 149f, 150f.

Learn more:

Vitamin D deficiency in modern society.

The Smörjning folk cure.

Ann Gustavsson is an archivist/curator at Karolinska Institutet’s Medical

History and Heritage Unit. She has a master’s degree in archaeology and another

in osteoarcheology. With a background in cultural studies, she went on to read

ancient history and archival science. Her speciality is pathological lesions in

bone. Ms Gustavsson is currently inventorying, analysing and digitalising

Karolinska Institutet’s anatomical skull collection.

Translation: Neil Betteridge