Inauguration speech for the exhibitionClarity and Truth, the Life of Jacob Berzelius in Biomedicum, Karolinska Institutet, 18 December, 2023

We have worked in this beautiful

building five years now. It’s full of life, full of science, full of productive

chance encounters.

But I remember my old office in

the Retzius lab, with French balcony windows that I could open in summer to

feel the breeze on my face. I could hear the birds chirping in the birch tree

outside, and sometimes Lennart Nilsson would be on his hands and knees on the

lawn outside using some new optical contraption to photograph the bumblebees.

It’s just nostalgia of course.

Our memories are often deceptive. The curtains in my old office were so ugly I

stuffed them into the electrical utility closet. The walls were incredibly ugly

too, but I couldn’t stuff them away.

I think anyone who steps into

Biomedicum is struck by the care and thoughtfulness that has gone into the

architecture. The building clearly works, where so many others do not.

Part of it is down to physical

organization. The atrium and the cafeteria downstairs. The single point of

entry. The slits. The open-door policy.

But also the interior design.

Clearly someone with good taste has selected the materials and the colors. The

wood, the textiles, the leather. The beautiful, muted shades of brown, green

and violet.

Why are the colors and the

materials so important? As scientists, we tend to focus on the rational. The well-crafted

argument, the precise measurement, the exact figure. But we are also artisans

engaged in a craft, using and transferring tacit knowledge. We use our hands a

lot. We work in small teams, humans interacting closely, intensely with each

other. Our teams are diverse, mixing ages, genders, nationalities, and social

backgrounds. As a consequence, even though we tend not to talk about it much,

science is profoundly emotional. It’s

hard emotional work — adapting, competing, collaborating, figuring each other

out. I think that’s why the beauty of the physical environment is so important

to us, whether we realize that or not.

One way to structure and navigate

complex human relationships is through collective memory. Shared memories can

support shared values. But memories — especially collective ones — are fragile

constructions that require nurturing and support. Losing your memory —

especially collective ones — can be devastating.

In his book One hundred years

of solitude, Gabriel Garçia Marques tells of the orphan Rebecca who brings

to the sleepy village of Macondo a plague of insomnia. But ”No one was alarmed

at first. On the contrary, they were happy at not sleeping because there was so

much to do in Macondo in those days that there was barely enough time.”

But soon, the insomnia leads to

amnesia. Villagers first lose memory of their childhoods. It gets worse and

eventually they begin to forget the names of everyday objects. To remember,

they start to place written labels on everything: ”table, chair, clock, door,

wall, bed, pan”. Thus, writes Marques, ”they went on living in a reality that

was slipping away, momentarily captured by words, but which would escape

irremediably when they forgot the values of the written letters”.

So, the dangers of amnesia are

obvious. But memories can also overwhelm. Jorge Luis Borges once told the story

of Ireneo Funes[1], who

fell off a horse and hit his head badly. Upon recovery, Funes found that he

would now remember everything: the shape of the clouds at every moment, and the

configuration of every leaf on every tree he had ever seen. It was a curse of

course. Funes was incapable of making any generalizations. A dog in the morning

was for him utterly distinct from the same dog seen in the afternoon.

But I’m rambling. I found a few

reports[2]

in the scientific literature of actual people diagnosed with hyperthymesia: the

inability to forget. Most of those reports are sketchy. There are many more of

course, reporting the inability to remember.

Even worse, in my opinion, is wilful

amnesia, the active lack of curiosity about our past. It is a trait that has

been unfortunately all too common at this institute. We have an entire museum

of Swedish medical history stuck in a storage facility. An entire museum! Our

library of old books, Hagströmerbiblioteket, is beautiful but hard to reach and

open only occasionally.

Consistently, another striking

design feature of this building, was the complete absence of any memories. You

step inside and you might as well think Karolinska was founded five years ago.

Today, that changes. I hope today can be the start of a new era, where

Karolinska Institutet can come to terms with, and celebrate all of its

memories, as inspiration for the public and the next generations of scientists.

I hope one day all our historical artefacts, memories of two hundred years of

Swedish medical science, can be on display to excite and provoke and educate

the public. Until then, I am so very pleased to welcome you to the first

permanent historical exhibit at Karolinska Intitutet: Clarity and Truth, the

Life of Jacob Berzelius.

Sten

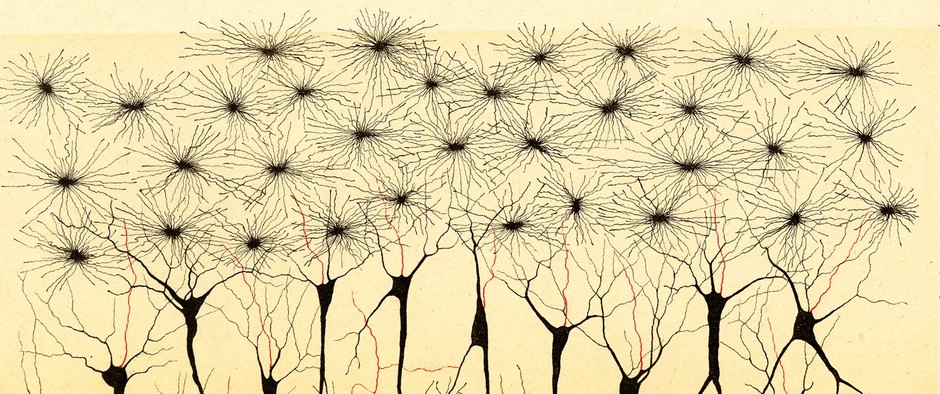

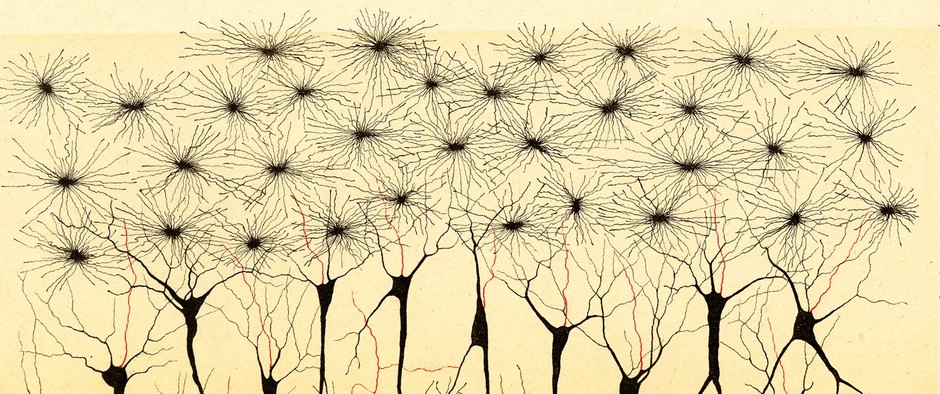

LinnarssonImage: Camillo Golgi,Sulla fina anatomia degli organi centrali del sistema nervoso.

Reggio-Emilia, Stefano Calderini e figlio, 1882, 1883, 1885.

[1] Funes, the

memorious, 1944. “Two

or three times he had reconstructed an entire day; he had never once erred or

faltered, but each reconstruction had itself taken an entire day.”

[2] E.g.

Jill

Price: "Starting

on February 5, 1980, I remember everything. That was a Tuesday."