The Swedish physician Christofer Carlander (1759-1848)

The Nordic Encyklopedia (Nordisk familjebok) published in 1905 stated that for a long period of time Christofer Carlander was the centre around which medical science in Sweden moved. At the same time he was one of the most experienced physicians. For 20 years, 1793-1814, he practised medicine in Gothenburg, and kept records of his 6000 patients. In all they comprise 2200 pages in folio, giving details of the diseases, the treatment and the outcome for each case. Many patients were followed for over ten years with new complaints. The document is unique in Sweden, if not in the world.

The patients were of all social classes, from the bishop’s wife to prostitutes, but servants and craftsmen predominated. Many details give ethnological evidence of life in the city. Carlander could be summoned at any time and went to see the same person up to five times a day if he saw the need. Only in the summer could he be free and leave the city for about three weeks, visiting friends and relatives in western Sweden, but some years he could not find anyone to replace him and from the summer of 1807 he was in constant service for three years.

He was well aware of the limitations of medical science of his time. His correspondence with his collegue and friend in Stockholm, Jonas Gistrén, which has also been preserved, reveals his concern. Positioned in Gothenburg he had the opportunity to import modern medical literature from London, for his own education as well as that of Gistrén, professor Pehr Afzelius in Uppsala and a couple of other prominent physicians who shared his eagerness to learn. A list of orders from 1801 contains 21 items for himself, among them ”Bell’s Engravings”, ”Haggarth on Fever”, ”Whately on Strictures” and ”Willan’s Diseas of London”.

Carlander dealt with all kinds of morbidity, even contributions by surgeons were recorded, including two cases of breast cancer. Specific diagnoses unknown at the time can be identified through his careful descriptions, e.g. a case of lung embolism during pregnancy and a myocardial infarction.

He was a skillful obstetrician, in many instances delivering babies with thongs. The local midwives were independent and proud of their methods, some very competent and involved in the care of women and small children in general. They cooperated well with Carlander, while others were reluctant to call for him, and still others were clearly incompetent.

Sometimes he had to find solutions to specific problems, such as rings in various sizes made of cork covered by wax for women with prolapse of the womb. An instrument to ligate the stalk of a benign polyp of the womb was manufactured by a local silversmith according to a design Carlander found in a German book printed i Jena in 1787. With that he prevented bleedings from being lethal in several cases.

Many patients were children with infectious diseases, worst of all smallpox, for which Carlander introduced vaccination in 1802. Within a couple of years he and his collegues carried out a programme that covered the whole Gothenburg population.

Among children and adults tuberculosis was frequent, the various forms called scrofula, comsumption or hectic disease. Numerous patients suffered from involvement of the hips or vertebras with resulting collapse and deformation.

Syphilis was another threat, often treated by quacks with mercury compounds on the mere suspicion or fear, but Carlander’s use of this remedy was more restricted. The disease was shameful, and he could not be sure that his records were not read by others, so in some cases he used witty synonyms for their names.

The texts were his private records and contain notes such as ”stubborn as hell”, ”big cow” and ”sweet child”.

Although in general Carlander made efforts to help in any illness, problems with sight and hearing in elderly patients were exceptions: ”Cannot be made young again”.

Death was constantly present in this society and Carlander took a special interest in the death process, keen that it should be calm and smooth, the patient prepared to leave, to say good-bye. He came to see patients even when death was close, to comfort them, and to prescribe valeriana, opium, jelly, and drinks soothed by salep.

In 1814, he retired to Stockholm, inaccessible to the many patients who never let him rest. There, he was mainly involved with administration and served as a referee of medical literature for The Swedish Society of Medicine. His vast collection of medical science books, which includes many copies of valuable ancient works, is now kept in the Hagströmer Library.

Gudrun Nyberg, 14 September 2016

Illustrations:

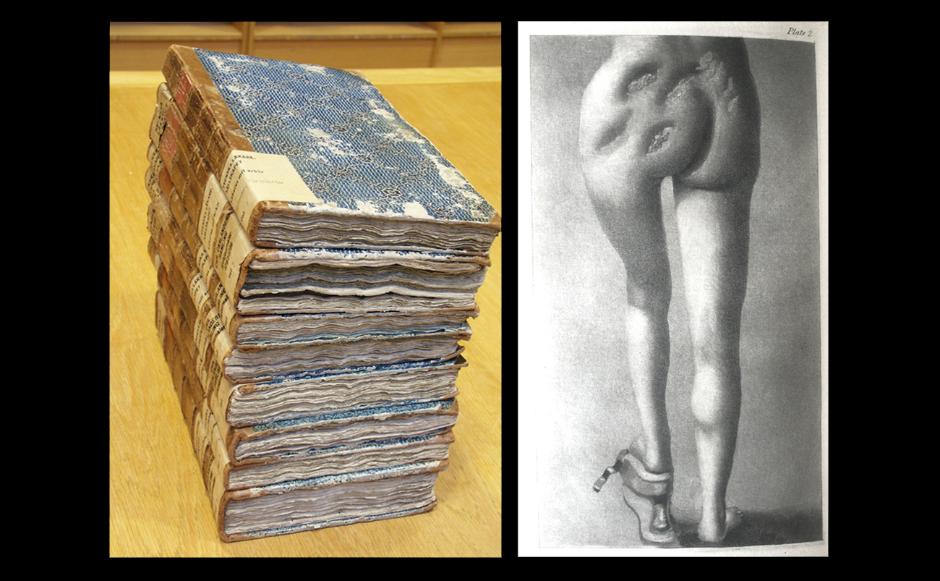

Carlander’s medical records, 2200 pages in folio, are kept at the National Archives in Stockholm.

One of Carlander’s books on scrofula (tb) was Edward Ford’s Observations on the Disease of the Hip Joint, London 1794.

Nyberg, Gudrun. Doktor Carlanders Göteborg – folkliv, sjukdom och död 1793-2014. Stockholm, 2007.

Nyberg, Gudrun. Doktor Carlander i praktiken – läkekonst 1793-1814. Stockholm, 2009.