I see dead people

In addition to skeletal samples gathered during archaeological excavations, various anatomical collections are housed in museums and institutions worldwide. In many cases, the acquirement of these samples may be questionable from an ethical point of view, and so the reason for upholding this practice has been questioned. Obviously, there is an ongoing important debate regarding ethics, reburials and the housing of human remains in different institutes, but that is a whole other story.

Osteologists (bone experts) and biological anthropologists (specializing in human skeletal remains) work with bones on a day-to-day basis. Unlike physicians, we examine the remains of people whose soft tissues decomposed a long time ago. We inspect the shape, appearance and size of the bones. We measure them: lengthwise, widthwise, girthwise. And from these observations, we assess age at death, sex and stature of people from long ago. In addition to this, chemical analyses of skeletal remains, such as DNA, isotopes and trace element analysis shed further light on past populations regarding genetic relationships, diet and much more.

Anthropologists spend hours on end starring into a pair of hollow eye sockets asking questions: Who are you? How can I get to know you, and the life you lived? What happened to you?

We then embark on the journey to find the answers to these, one might argue, impossible questions. In our efforts to do so, skeletal traits or anomalies caused by severe living conditions, disease or trauma are examined, recorded and scrutinized in detail. The next step is to analyze and interpret the findings. How far you choose to go in your interpretations is entirely up to you and your scientific conscience.

My professional interests recently shifted from prehistoric life-ways to injuries inflicted through criminal actions. This transition started a few years back, just before I began my two-year training at the Police Academy in Stockholm, when a colleague at the Archaeology Department of Stockholm University introduced me to a unique “case”: A man who lived and died around 2500 years ago during the Swedish late Bronze Age. His remains were discovered and exhumed 130 years ago during peat digging in southern Sweden. His bones exhibited no less than 700 various injuries, including blunt and sharp force trauma. For me, this undertaking was to become a natural progression from archaeology into the world of forensics.

As a scientist, I established that his injuries were inflicted in a certain order of events, manner of execution and possible technique(s) used. On a more personal level, I might venture more spectacular conclusions. Yet, as this is not the forum for vivid descriptions of his wounds, it suffices to say: He died a gruesome and painful death.

He had received several blows to the head causing some very specific injuries: three nearly identical circular fractures. I and several experienced colleagues were puzzled by their appearance and regularity. Just prior to this, I had recorded and documented remains from an anatomical collection (now kept by the Medical History and Heritage Unit at Karolinska Institutet), that were stored at Stockholm University at the time. I remembered two skulls from the collection that both had very similar rounded injuries. Attached to those two skulls were two pieces of paper with writing in black marker and the same handwriting: “Murder” and “Blow with hammer” as well as the same case number.

The comparisons with the wounds found on the remains from the anatomical collection kept by the Medical History and Heritage Unit, thus provided a plausible interpretation of the shape of the implement used, and the manner of in which the circular fractures were inflicted to the Bronze Age man.

So, it is evident that the anatomical collection comprises a very valuable source of information, and a clearer image of what happened to that man many years ago emerges. Now new questions arise: What ultimately killed him? What implements were used? Who killed him? And why was he killed? I can’t shake the feeling that he himself might not have been completely innocent. The questions remain unanswered, but will always be open for exploration, discussion and interpretation.

And ultimately, there is a significant difference between archaeology and forensics: In archaeology, we don’t have to worry that our interpretations are responsible for condemning an innocent for a crime (?) committed more than 2000 years ago.

Petra Molnar, 6 September 2016

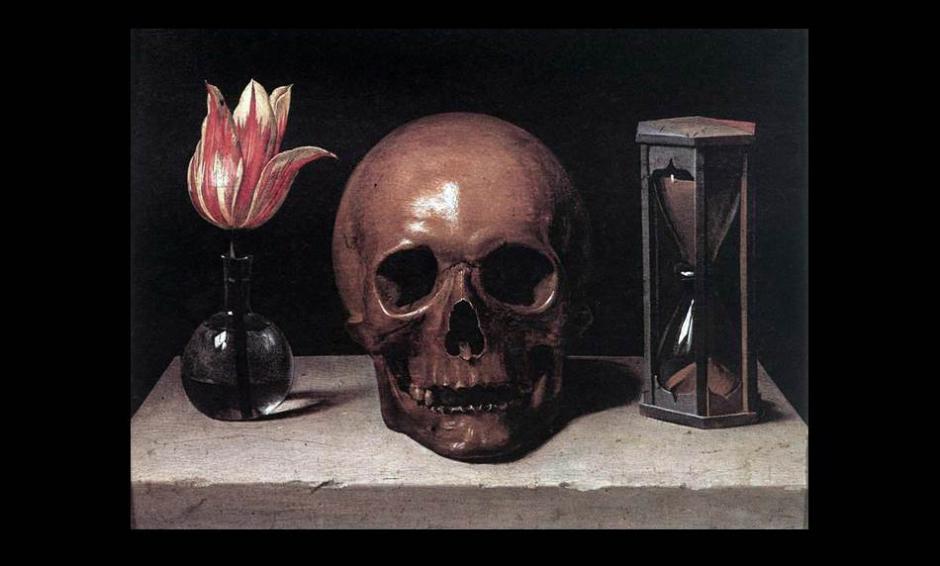

Illustration from:

Still-life with a skull, oilpainting, Philippe de Champaigne 1644. Tessé Museum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Philippe_de_Champaigne_Still-Life_with_a_Skull.JPG?uselang=s... (accessed 2016-09-06).

Petra Molnar earned her PhD in Osteoarchaeology from Stockholm University in 2008 and graduated from the Swedish Police Academy in 2014. She recently participated in the Visiting Scientist Program offered by the Forensic Anthropology Unit at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner’s Office in New York City. She is currently working as a Crime Scene Investigator and Forensic Anthropologist at the Swedish Police Authority in Stockholm, Sweden.