WIRSUNG, Christoph (1500–1571)

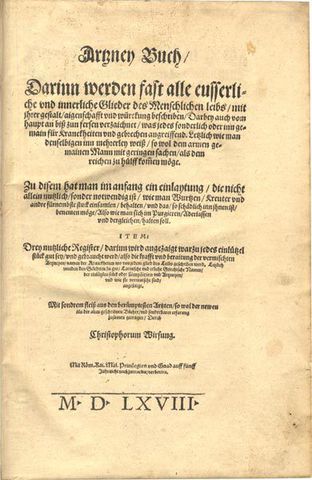

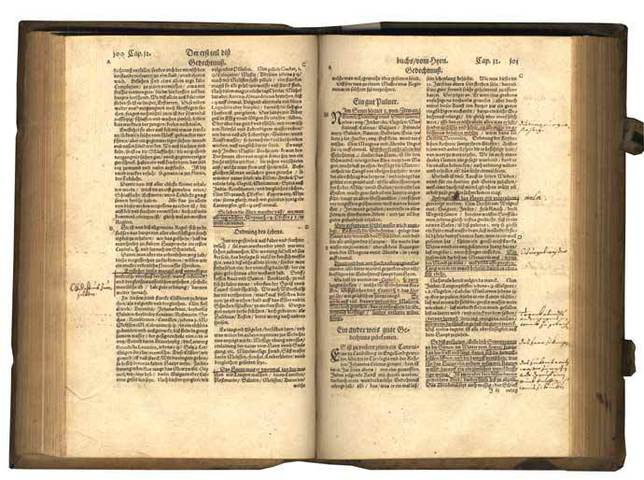

Artzney Buch, Darinn werden fast alle eusserliche und innerliche Glieder des Menschlichen leibs, mit jhrer gestalt, aigenschafft und würckung beschriben. Darbey auch vom Haupt an biß zun fersen verzaichnet, was jedes sonderlich oder inn gemain für Kranckheiten und gebrechen angreiffend. Letzlich wie man denselbigen inn mehrerley weiß, so wol dem armen gemainen Mann mit geringen Sachen, als dem reichen zu hülff kom[m]en möge. Zu diesem hat man im anfang ein einlaytung, die nicht allein nutzlich, sonder notwendig ist, wie man Wurtzen, Kreuter und andre fürnembste Stuck einsamlen, behalten, und das so schädlich inn ihnen ist, benemen möge. Also wie man sich im Purgieren, Aderlassen und dergleichen, halten soll. ... Mit sondrem fleiß aus den berümptesten Artzten so wol der newen als der alten geschribnen Bucher und sonderbarer Erfarung zusammen getragen.

Heidelberg, Johannes Mayer, 1568.

First edition of this popular book, which went through several editions. Wirsung’s Artzney Buch was one of the sources for Benedictus Olaii Een nyttigh läkere book (Stockholm, 1578), the first Swedish medical book.

Christof Wirsung was a friend of Conrad Gesner and he was a similar encyclopedic character. The text is especially important for the large number of recipes that do not go back to ancient models, but were created by Wirsung himself and his contemporaries.

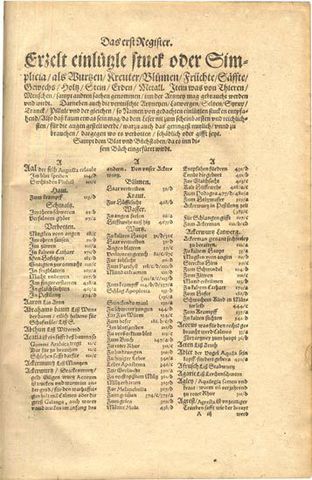

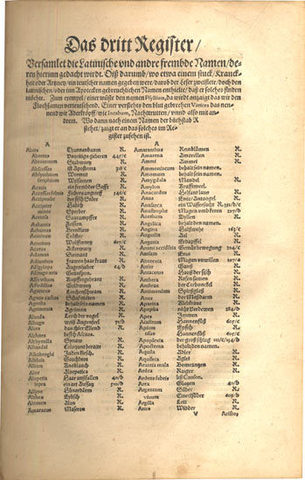

Wirsung worked as a doctor, pharmacist, councilor, translator as well as being the author of this influential Artzney Buch recipe collection. He composed this work late in life while residing in Heidelberg. The first quarter this large volume consists of three very detailed and extensive indexes (of pharmacological recipes, diseases, and Latin names) which greatly increased its usefulness as handbook. In it Wirsung organizes his approximately 15,000 recipes. He wanted to enable both the urban and rural populations to correctly recognize and assess diseases and to guide them in using the appropriate medicines for healing. He emphatically writes, he not only wanted to provide information about expensive medicines, but also to offer medicines for those with a smaller budget. Wirsung divided his "Artzney Buch" according to the classic "a capite ad calcem" order (from head to feet) into four parts, in which the head, chest, abdomen and the organs inside them as well as the limbs and their diseases are treated. Each section has a theoretical and practical part. Four other parts are added, in which skin diseases, fever as an independent disease, the plague and poisoning are described; attached is an eighth part, in which gingerbread, spice wines, oils, water of life and gold are described with detailed manufacturing instructions. The sections dedicated to the individual diseases, in which the cause and treatment of the complaints are explained, always follow the same schematic structure. The final section on 'regiments' means that the patient receives detailed instructions regarding his entire lifestyle. Including dietary recommendations for eating and drinking, as well as rules of conduct for the daily routine, sleeping and waking, exercise and rest, sexual intercourse, clothing, and home furnishings. The range of medicines ranges from quite simple, practically free home remedies to more expensive treatments.

Following its first appearance in Heidelberg in 1568 it quickly became a valued reference work, going through numerous reprints and translations into Dutch and English. The theoretical explanations lift Wirsungs's work far beyond a common German pharmacopoeia of the time and made it equally a medical textbook for the reader.

The work is also of special interest the numerous and extensive sections dealing with one of the great imported botanicals from the New World, Guaiacum, to which he also provides the other popular names for it: Franzosenholtz, Indianisch holz, and Lignum Sanctum in addition to Guaiacum. Curiously, Alden-Landis’s European America notes only the 17th century editions which correctly cite the 1568 first edition but it evidently hadn't been identified in time to appear in the appropriate volume. Wirsung includes a substantial section on the treatment of the New World disease, syphilis (French disease), which also uses the New World botanical Guaiacum as a cure.

Collation: Pp (240), 1-456, 456-691, (2) errata & colophon, and the final blank leaf (3M6).

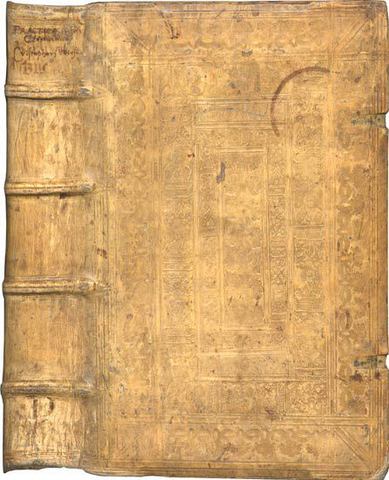

Binding: Contemporary blind-stamped pig skin, one border with the Evangelists. One (of two) brass clasp and ditto catcher, the other missing. Spine divided into five compartments with hand written title at head.

Provenance: Once in the library of Queen Christina of Sweden. When removing the modern red label with shelf number in the lower spine compartment of the above book the letter "P" was discovered. This "P" was the marking of scientific and medical books in Queen Christina's library, catalogued by the Dutch scholar and manuscript collector Isaac Vossius, who had been invited to Stockholm by the Queen to be her royal librarian. When Christina left for Rome she brought many books with her and due to lack of money Vossius was paid in natura with a box full of books, which probably included the 6th century Gothic manuscript, Codex Argenteus. Back in Holland Vossius lent out the book to his uncle, Fransiscus Junius in Dordrecht, a pioneer in German philology, who published the first modern edition, the editio princeps (1665) of the Silver Bible. In 1662 the book was announced for sale by Vossius and Christina commissioned a man to buy back the Bible, however too late. The book was purchased by Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie, and is today one of the great treasures at the Uppsala University Library.

References:

§ VD 16, W 3605; Durling 4751; Parkinson-Lumb 2613; Ferchl p. 583; cf. Wright, Science and the Renaissance, no. 733 (1617 English ed.).

Waller 10361.