BECKER [BEKHER], Daniel (1594–1655)

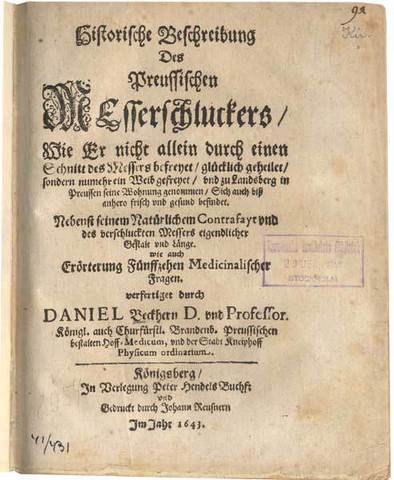

Historische Beschreibung des Preussischen Messerschluckers, wie Er nicht allein durch einen Schnitt des Messers befreyet, glücklich geheilet, sondern numehr ein Weib gefreyet, und zu Landsberg in Preussen seine Wohnung genommen, Sich auch biss anhero frisch und gesund befindet. Nebenst seinem Natürlichem Contrafayr und des verschluckten Messers eigendlicher Gestalt und Länge. Wie auch Erörterung Fünffzehen Medicinalischer Fragen.

Königsberg, In Verlegung Peter Hendels Buchst und Gedruckt durch Johann Reusnern, 1643.

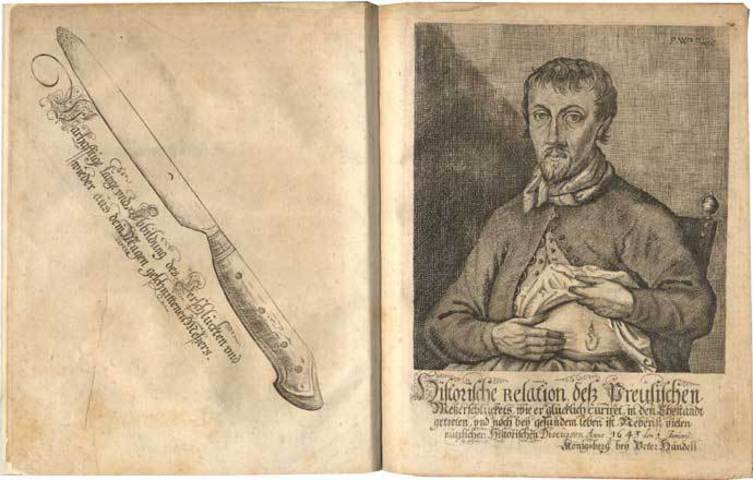

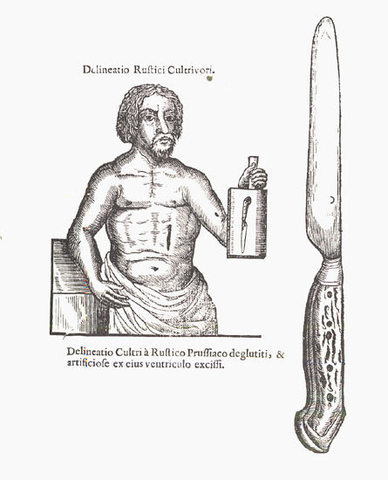

This remarkable book was first published in Latin under the title of De cultrivoro Prussiaco observatio & curatio singularis in Königsberg (Regiomonti), 1636. This is the first German edition, revised and enlarged. An unusual case in the history of seventeenth-century surgery. In the morning of the 29th of May, 1635, Andreas Grünheide, a young farm hand from Grünenwald outside Königsberg awoke feeling nauseous. To provoke vomiting, he tickled his throat with the shaft of a long knife; the blade slipped from his fingers and the knife descended into the lower esophagus. Grünheide stood on his head but to no avail. To moisten his throat he took a drink of beer, whereupon the knife slid into his stomach. Daniel Becker, professor of medicine in Königsberg, brought his patient to Königsberg for consultation with the entire Medical College. The decision to remove the knife by incision was agreed upon, and the operation was performed on July 9 1635 by Daniel Schwabe, a wound and lithotomy surgeon, in the precense of Becker and other local physicians. The patient was bound to a board, the knife located with a magnet and the site selected for the incision over the palpable point of the swallowed knife was marked with charcoal. On its withdrawal, Grünheide joyfully announced it was his knife. The gastric wound was closed and the patient recovered completely, returning to his farm work and married in 1641. The operation was so sensational that the patient and his knife were immortalized by an oil painting and the King of Prussia retained the knife as a souvenir. There were several editions of this surgical case, but this German one is the best with copper engraved illustrations instead of woodcuts depicting the portrait of the patient showing his large scar and the knife in natural size.

Collation: Pp (144). With 2 full-page engravings. Sign. *4 (= letterpress title, two full-page engravings, versos blank) A6 B-Q4 R2.

Binding: Early 20th century green half cloth.

References: Hirsch I, 415-16; Rutkow p 208 (with reproduction of the woodcut portrait in the 1640 edition); Krivatsy 1007; Waller 818, 819, 820 (all Latin editions); Wangensteen, Owen H. and Sarah D. The Rise of Surgery. From Empiric Craft to Scientific Discipline (1979), pp 143-44. Waller 818, 819, 820 (all Latin editions)